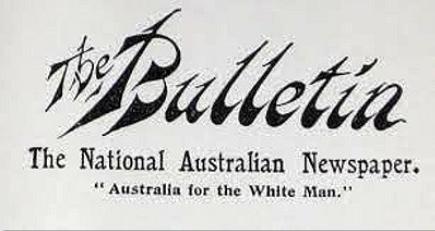

“Australia for the White Man”

“Australia for the White Man”

The Bulletin was Australia’s longest running magazine,founded by J. F. Archibald and John Haynes and first published in Sydney on January 31 in 1880. They ‘had about £140, which they used to buy a small case of battered display type, put a deposit on a second-hand press and rent the Scandinavian Hall at 107 Castlereagh Street’. Initially Haynes sold advertising while Archibald gathered copy, wrote and subedited.

The original content of The Bulletin consisted of a mix of political comment, sensationalised news, and Australian literature.The publication’s focus was politics and business, with some literary content, and editions were often accompanied by cartoons and other illustrations. The Bulletin was highly influential in Australian culture and politics. In the early years, The Bulletin played a significant role in the encouragement and circulation of nationalist sentiments that remained influential far into the next century.

Men of learning had contributed to the nationalist surge. Especially in the 1890s and through the Sydney Bulletin, verse and prose portrayed the Outback as the home of the true Australian—the bush worker: tough, laconic, and self-reliant but ever ready to help his “mate.” The Bulletin was nationalist, even republican, and much more radical than the federalist politicians. Henry Lawson and Joseph Furphy were the supreme writers of the nationalist school. Painters and poets also extolled the nationalist ideal.

“Henry Lawson, ‘Banjo’ Paterson, Henry Kendall, Victor Daly, G. H. ‘Ironbark’ Gibson, Will Ogilvie and George Essex Evans, to name only a few, delivered a steady literary diet that shaped and reshaped the Australian identity. Much of their writing echoed the bohemian traits of new urban journalism, being almost a caricature of the Australian legendary characteristics portrayed by the journal: mateship, unionism, anti-wowser, anti-authority – whilst earnestly cheering drinking and gambling, and nodding to republicanism. It was the Bushman’s Bible that carried this mythical creation to the bush and back.”

(Warren Fahey, ‘Colloquial Sayings and Slanguages – The Bushman’s Bible:The History of The Bulletin’, first published in The Bulletin, February 1 in 2005).

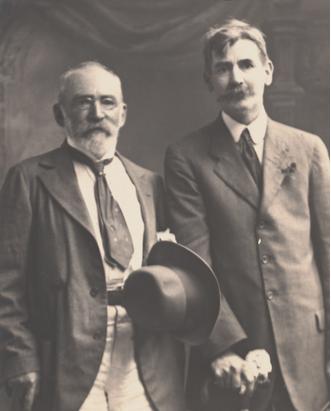

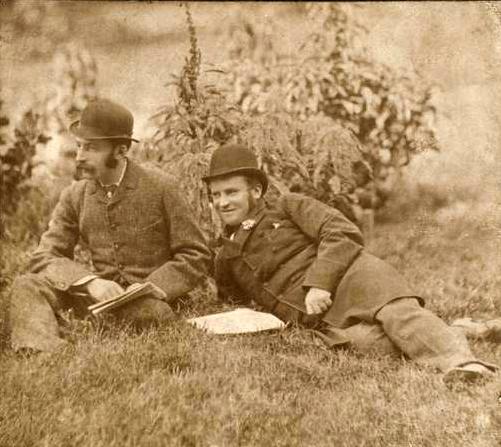

Portrait of JF Archibald and Henry Lawson, Sydney, 1918. Ferguson collection of photographs,

Portrait of JF Archibald and Henry Lawson, Sydney, 1918. Ferguson collection of photographs,

National Library of Australia, an23351940-v

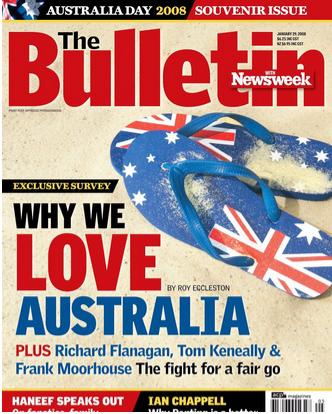

The final issue was published in January 2008. We reproduce selected copies below in PDF and below the list links we reproduce some articles wrtten about The Bulletin.

.

The Bulletin was an Australian magazine first published in Sydney on 31 January 1880.

The publication’s focus was politics and business, with some literary content, and editions were often accompanied by cartoons and other illustrations. The views promoted by the magazine varied across different editors and owners, with the publication consequently considered either on the left or right of the political spectrum at various stages in its history.

The Bulletin was highly influential in Australian culture and politics until after the First World War, and was then noted for its nationalist, pro-labour, and pro-republican writing. It was revived as a modern news magazine in the 1960s, and was Australia’s longest running magazine publication until the final issue was published in January 2008.

The Magazine’s Early History

The Bulletin was founded by J. F. Archibald and John Haynes, with the first issue being published in 1880. The original content of The Bulletin consisted of a mix of political comment, sensationalised news, and Australian literature. For a short period in 1880, their first artist William Macleod was also a partner.

The Bulletin founders J. F. Archibald and John Haynes (Photo of 1882)

In the early years, The Bulletin played a significant role in the encouragement and circulation of nationalist sentiments that remained influential far into the next century. Its writers and cartoonists regularly attacked the British, Chinese, Japanese, Indians, Jews, and Aborigines. In 1886, editor James Edmond changed The Bulletin’s nationalist banner from “Australia for Australians” to “Australia for the White Man”. An editorial, published in The Bulletin the following year, laid out its reasons for choosing such banners.

By the term Australian we mean not those who have been merely born in Australia. All white men who come to these shores—with a clean record—and who leave behind them the memory of the class distinctions and the religious differences of the old world … all men who leave the tyrant-ridden lands of Europe for freedom of speech and right of personal liberty are Australians before they set foot on the ship which brings them hither. Those who … leave their fatherland because they cannot swallow the worm-eaten lie of the divine right of kings to murder peasants, are Australian by instinct—Australian and Republican are synonymous.

As The Bulletin evolved, it became known as a platform for young and aspiring writers to showcase their short stories and poems to large audiences. By 1890, it was the focal point of an emerging literary nationalism known as the “Bulletin School”, and a number of its contributors, often called bush poets, have become giants of Australian literature – Henry Lawson, C. J. Dennis, Andrew Barton ‘Banjo’ Paterson, Mary Gilmore, Dorothy Mackellar, Henry Kendall, Victor Daly, G. H. ‘Ironbark’ Gibson, Will Ogilvie and George Essex Evans and celebrated others (see list below).

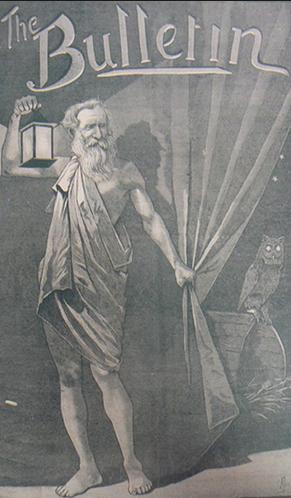

Cover of The Bulletin, vol. 7, no. 347, 25 September 1886.

Notable Writers with The Bulletin

Notable writers associated with The Bulletin at this time include:

• Barbara Baynton

• George Lewis Becke

• Christopher Brennan

• Victor Daley

• Frank Dalby Davison

• C. J. Dennis

• Edward Dyson

• Joseph Furphy

• Mary Gilmore

• Henry Lawson

• Dorothy Mackellar

• Harry ‘The Breaker’ Morant

• John Shaw Neilson

• Will H. Ogilvie

• Nettie Palmer

• Vance Palmer

• Andrew Barton ‘Banjo’ Paterson

• Katherine Susannah Prichard

• Steele Rudd

• Louise Mack

• Ethel Turner

• Alexina Maude Wildman

In English author D. H. Lawrence’s 1923 novel Kangaroo, he writes of a character who reads The Bulletin and appreciates its straightforwardness and the “kick” in its writing: “It beat no solemn drums. It had no deadly earnestness. It was just stoical and spitefully humorous.” In The Australian Language (1946), Sidney Baker wrote: “Perhaps never again will so much of the true nature of a country be caught up in the pages of a single journal”. The Bulletin continued to support the creation of a distinctive Australian literature into the 20th century, most notably under the editorship of Samuel Prior (1915–1933), who created the first novel competition.

Life in the Australian bush of the nineteenth century was intolerably lonely and, for many, especially the itinerant workforce, made worse by the lack of intellectual stimulation. For the first thirty-five of its one hundred and twenty-five years The Bulletin enjoyed the affectionate moniker of The Bushman’s Bible; and with good reason.

The Bulletin’s banner openly addressed the burning issues of the day: Australia for the Australians, Australian nationalism, the rights of abandoned rural Australia, sovereign national independence, cracking down on mass immigration and foreign scab labour – especially from the barbaric Third World. The Bulletin cleverly bridged the gap between city and bush readers and benefited from improved delivery systems and a flow of controversial issues.

January 22, 1881: The Bulletin advertised, ‘Every bushman should have The Bulletin mailed to him every quarter.’ In the December 15 issue, 1888, it went as far as to describe itself as ‘The Bushman’s Bible’. Sidney J. Baker, author of pioneering works on our language commented: “The simple facts are that the material on bush lore, slang and idiom, collected by thousands of writers in The Bulletin pages is absolutely irreplaceable.”

As former writer with The Bulletin, Warren Fahey atests: “Through prose and verse these contributors helped define ‘the real Australian’ as male, white and a hard-yakka worker. We could be colonial-born or British ‘new chum’. Australians saw themselves as whiter than white and better than British. We had been born of a cruel convict system, grew up in the bush and were now living in God’s-own country.”

The Bulletin’s Later Era under Packer

The literary character of The Bulletin continued until 1961, when it was brought by Australian Consolidated Press (ACP), merged with the Observer (another ACP publication), and shifted to a news magazine format. Donald Horne was appointed as chief editor and quickly removed “Australia for the White Man” from the banner. The magazine was costing ACP more than it made, but they accepted that price “for the prestige of publishing Australia’s oldest magazine”. Kerry Packer, in particular, had a personal liking for the magazine and was determined to keep it alive.

In 1974, as a result of its publication of a leaked Australian Security Intelligence Organisation discussing Deputy Prime Minister Jim Cairns, the Whitlam Government called the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security.

In the 1980s and 1990s, The Bulletin’s “ageing subscribers were not being replaced and its newsstand visibility had dwindled”. Trevor Kennedy convinced publisher Richard Walsh to return to the magazine. Walsh promoted Lyndall Crisp to be its first female editor, but James Packer then advocated that former 60 Minutes executive producer Gerald Stone be made editor-in-chief. Later, in December 2002, Kerry Packer anointed Garry Linnell as editor-in-chief.

Kerry Packer died in 2005, and in 2007 his son James Packer sold controlling interest in the Packer media assets (PBL Media) to the private equity firm CVC Asia Pacific. On 24 January 2008, ACP Magazines announced that it was shutting The Bulletin. Circulation had declined from its 1990s’ levels of over 100,000 down to 57,000, which has been attributed in part to readers preferring the internet as their source for news and current affairs.

Editors of The Bulletin

The Bulletin had many editors over its time in print, namely:

• J. F. Archibald

• John Haynes

• William Henry Traill

• James Edmond

• Samuel Prior

• John E. Webb

• David Adams

• Donald Horne

• Peter Hastings

• Peter Coleman

• Trevor Kennedy

• James Hall

• Lyndall Crisp

• Gerald Stone

• Max Walsh

• David Dale

• Paul Bailey

• Garry Linnell

• Kathy Bail

• John Lehmann

Ownership by S. H. Prior

Samuel Henry Prior (10 January 1869 – 6 June 1933) was an Australian journalist and editor, best known for his editorship and ownership of The Bulletin. Born in Brighton, South Australia, Prior was educated at Glenelg Grammar School and the Bendigo School of Mines and Industries. He started his career as a teacher, before becoming a mining reporter at the Bendigo Independent. In 1887, he was assigned to Broken Hill, New South Wales, to report on the silver mine. He was briefly editor at the Broken Hill Times and then at its successor, Broken Hill Argus. In 1889, Prior joined the Barrier Miner as editor, remaining in the role for 14 years,[23] during which time he displayed nationalism and championed trade unionism and the Federation of Australia.

After sending some of his work to J. F. Archibald at the Sydney Bulletin, he was appointed finance editor in 1903. In this role, he increased importance of the “Wild Cat” column, a financial and investment news and insights column focused on mining companies, which eventually (by 1923) grew into Wild Cat Monthly. Prior was promoted to associate editor in 1912. In 1914, Archibald sold his shares in The Bulletin to Prior, making Prior the majority shareholder. In 1915, he became the senior editor, in which position he built The Bulletin’s reputation for literature and for financial journalism. In 1927, he was sold the remaining shares in The Bulletin and thus became not only its editor but its sole owner and manager. In 1928, he inaugurated the first Bulletin Novel Competition, offering aspiring writers prize money and the publishing of their work in The Bulletin.

Prior remained editor until 1933, when he died from heart disease. In 1935, his son established the S. H. Prior Memorial Prize for a work of Australian literature. Prior’s family retained control of the magazine until it was bought by Consolidated Press Ltd in 1960.

Garry Linnell, Editor-in-Chief from 2002

Garry Linnell joined The Bulletin in 2001 and became editor-in-chief in 2002, when the magazine was already dropping in circulation and running at a loss. On one occasion, Kerry Packer called Linnell to his office, and, when Linnell asked what Packer wanted for The Bulletin, Packer said: “Son, just make ’em talk about it.” When former Prime Minister Paul Keating sent Linnell a letter criticising the magazine and calling it “rivettingly mediocre”, Linnell published the letter in the magazine, promoted that “Paul Keating Writes for Us”, and awarded Keating with “Letter of the Week”, with the prize for that being a year’s subscription to the magazine. In 2005, Linnell offered a $1.25-million reward to anyone who found an extinct Tasmanian tiger.

The Bulletin, by Garry Wotherspoon, 2010

‘The Bulletin, Australia’s longest-running magazine, would surely be on any short-list of controversial Sydney publications. On its masthead, from the first issue until the early 1960s, was the clarion cry ‘Australia for the White Man’, a statement that ignored the original inhabitants of the continent, from whom the ‘white man’ had wrested it, as well as the many non-white immigrants who had come to Sydney.

The Bulletin was founded in January 1880, established by journalist Jules François (born and baptised John Feltham) Archibald, and journalist and politician John Haynes. They ‘had about £140, which they used to buy a small case of battered display type, put a deposit on a second-hand press and rent the Scandinavian Hall at 107 Castlereagh Street’. [1] Initially Haynes sold advertising while Archibald gathered copy, wrote and subedited.

There had been some dispute about the title of their new publication: Haynes wanted the Tribune, while Archibald favoured the Lone Hand; they settled for naming the paper after San Francisco’s Bulletin.[2] It was intended to be a journal of political and business commentary, with some literary content, and the first issue appeared on 31 January 1880, costing fourpence, and its stories of the hangings of Captain Moonlite and the Wantabadgery bushrangers grabbed readers’ attention – its 3,000 copies soon sold out. Success followed and circulation built to 15,000 within 18 months, reaching 80,000 by 1900.

The Bulletin has been described as ‘racist, isolationist, protectionist and “masculine”‘. [3] It certainly tapped into a vein of something very Australian. It gave its readers a perspective they weren’t getting in their newspapers, which usually drew their inspiration from ‘home’ – Britain.

Though it was a Sydney publication, it quickly earned the title of the ‘bushman’s bible’, and was a conduit connecting the cities of Australia with rural communities, thereby facilitating the emergence of bush poetry as a popular cultural artefact throughout the continent. Even though the Bulletin’s poetry covered stories from all walks of life, the romantic portrayal of rural life was one of its strengths. In pre-Federation Australia, this was critical in defining a romanticised version of ‘Australianness’.

From 1886, Archibald opened the magazine up to contributions from its readers, and this led to a flow of poetry, short stories and cartoons from all over Australia, contributed by miners, shearers and timber-workers, as well as urban dwellers. Some of this material was of high quality, and over the years many of Australia’s leading literary lights had their start in the Bulletin’s pages: it was here that The Man from Snowy River first appeared. It was the Bulletin’s literary editor, Alfred Stephens, who was a guiding force in creating the magazine’s literary reputation, including the so-called ‘ Bulletin school’. Its ‘Red Page’ on page 2 was a page of literary gossip and opinions, and was widely read, even until late in the twentieth century. At the same time, the Bulletin ran well-informed political and business news.

The Bulletin gave an Australian perspective on everything – on society, events and politics – and it was noted for its larrikin spirit. Its view on the plague in Sydney in 1900, which engendered panic and hysteria, allowed it to have a swipe at a few sacred cows:

So far the Plague…is a very small affair. It isn’t a patch on the daily, hourly typhoid as a means of slaughtering the public, and so far it has proved about as safe as football, and much safer than it was a few weeks ago to have doubts concerning the absolute justice of the war in South Africa. [4]

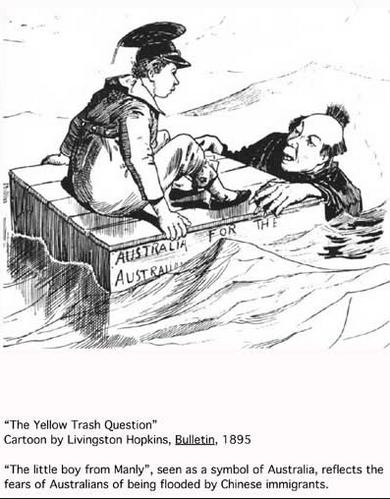

But it wasn’t just what the Bulletin wrote about or the slant that it took – it was also who was doing the writing and illustrating. Over its long history, the magazine published virtually every major Australian author and ‘black-and-white’ artist; this was a time when cheap colour reproduction was not possible. Its contributors list reads like a Who’s Who of Australian art, literature, and economic and political commentary. Early contributors included writers such as AB (Banjo) Paterson, Henry Lawson and Miles Franklin, poet Victor Daley, and cartoonists Phil May, David Low and Livingston (Hop) Hopkins.

Among the artists, the Lindsay brothers had a strong association with the Bulletin. Norman Lindsay was lured to Sydney by Archibald, after John Elkington, a friend of the Lindsay brothers from Melbourne who was attracted to the Bulletin’s style of nationalism, showed some of Norman’s Decameron drawings to Alfred Stephens, who described them in the Bulletin as ‘the finest example of pen-draughtsmanship of their kind yet produced in this country’. [5]

Archibald offered Norman a job, and in May 1901 Norman visited Sydney and accepted Archibald’s offer of £6 a week to join the Bulletin as a staff artist providing cartoons, decorations and illustrations for jokes and stories. The association was to last, with a few breaks, for over 50 years. More than any other artist, Norman Lindsay gave visual definition to the Bulletin’s editorial policy, particularly its nationalism and racism – Aborigines invariably figured as comics, Jews as old-clothes dealers with hooked noses. [6] Norman’s brother Lionel returned to Australia from Europe early in 1903, and Banjo Paterson offered him a job as a cartoonist for £4 per week with the right to contribute illustrations to the Bulletin. He soon became a freelance illustrator for the magazine, and his brother Percy Lindsay also saw his illustrations appear in the Bulletin.

As its masthead statement implied, it wasn’t shy of controversies. It was political from the outset, but after Archibald retired in 1907 the Bulletin became steadily more conservative. This marked its break with the political left and perhaps the end of its significant political influence, since by World War I it had become openly ‘Empire-loyalist’. In 1916–17 the paper supported conscription and Prime Minister WM (Billy) Hughes at a time when Australia’s involvement in a war – derided in some quarters as ‘an imperialist war’ – divided the nation.

Between the wars, the magazine steadily declined, in influence and circulation. Its admiration of the bushman was anachronistic as Australia became highly urbanised. Share sales led to the Prior family owning the Bulletin from the 1920s, and by the 1940s the Bulletin was regarded as a relic of past times, notable for extremely right-wing politics complete with anti-Semitism and racism. Yet it still retained its place in Australian literary life well into the twentieth century.

By the late 1950s, still ‘radically’ conservative and losing money, it was seen as a virtual basket case. But in 1961 it was sold to Australian Consolidated Press (ACP), whose owner, Sir Frank Packer, had an eye for media opportunities. He appointed Donald Horne editor, and the racist statement ‘Australia for the White Man’ disappeared. Despite its declining reputation and revenues, Sir Frank Packer, and later his son Kerry Packer, were prepared to subsidise the magazine, as it had a cachet that the other magazines of the ACP stable, including the Women ‘s Weekly, didn’t have. The Bulletin remained politically conservative, but rejoined the political and journalistic mainstream, as a well-edited magazine of political and business news and commentary, with forays into literature as a gesture to its past.

Not all these forays were successful. In 1961, the poet Gwen Harwood sent two sonnets into the Bulletin, under the name of Walter Lehmann, an ‘apple orchardist in the Huon Valley in Tasmania, and husband and father’. Horne published the poems, to his later embarrassment when it was revealed that, read acrostically, the sonnets read ‘So Long Bulletin’ and ‘Fuck All Editors’. Harwood believed that the sonnets were ‘poetical rubbish and [would] show up the incompetence of anyone who publishe[d] them ‘. [7]

In its last years as part of the Packer stable, the Bulletin had something of a resurgence, as ACP invested more heavily in it, attracting Sydney writers of the calibre of Peter Carey, Les Carlyon, Paul Toohey, Tim Flannery and Maxine McKew. Its last edition featured lengthy articles by Tom Keneally, Frank Moorhouse and Richard Flanagan.

Stories about the Bulletin abound. One of the better ones is as follows:

former Prime Minister Paul Keating loathed the Bulletin. On one occasion, he sent a stinging – but brilliantly written – letter to the editor Garry Linnell, claiming that he found the publication ‘rivettingly mediocre’. Linnell not only published the letter, but promoted the fact that ‘Paul Keating Writes for Us’. He then awarded the Letter of the Week to Paul Keating, Potts Point, NSW, and for Keating the problem was the prize – a year’s subscription to the Bulletin! To Keating’s great fury, for the next 12 months a copy of the Bulletin would arrive in his mailbox every Wednesday morning. [8]

The magazine’s twentieth-century peak came in the early 1990s, when editor David Dale took circulation to more than 100,000. But the era of news magazines was in decline – partly economics, partly falling victim to the power of the internet. The magazine, with a Wednesday publication date, seemed expensive compared to fat Saturday newspapers, and free commentary on the internet.

In its last years, the Bulletin had about 35,000 subscribers, and if it had a strong cover that attracted publicity, its sales at news stands might reach 20,000, well down from the level of the mid-1990s. By the early years of the twenty-first century, it had fallen on hard times – or the times had moved on – and in the end the Bulletin was overtaken by history. A controlling share in the Packers’ company PBL was bought by a foreign-based company, CVC Asia Pacific in 2007, and within a year the closure of the Bulletin was announced. While acknowledging the magazine’s long history and recent editorial successes, CVC Asia Pacific said that despite the best efforts of management, the magazine was no longer commercially viable. The Bulletin closed in January 2008, after 128 years of continuous publication.

References

The Bulletin Centenary: 1880–1980 Souvenir Edition, Australian Consolidated Press, Sydney, 1980

Sylvia Lawson, The Archibald Paradox, A strange case of authorship, Allen Lane, Ringwood, Victoria, 1983

Sylvia Lawson, ‘Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919’), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 43–48, available online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

John Lyons, ‘Foreign buyers silence the Bulletin’, Australian, 25 January 2008, at http://www.news.com.au/national/foreign-buyers-silence-the-bulletin/story-e6frfkvr-1111115393821, viewed 26 August 2010

Patricia Rolfe, The Journalistic Javelin; an Illustrated History of the Bulletin, Wildcat Press, Sydney, 1979

Notes

[1] Sylvia Lawson, ‘Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919’), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3 Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 43–48, available online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[2] Sylvia Lawson, ‘Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919’), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3 Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 43–48, available online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[3] Mark McKenna, the captive republic: a history of republicanism in Australia, 1788–1996, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p 153

[4] Bulletin, 31 March 1900, p 6

[5] Bernard Smith, ‘Lindsay, Norman Alfred Williams (1879–1969)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 106-115, available online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100676b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[6] Bernard Smith, ‘Lindsay, Norman Alfred Williams (1879–1969)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 106-115, available online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100676b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[7] Cassandra Atherton, ‘”Fuck All Editors”: The Ern Malley Affair and Gwen Harwood’s Bulletin Scandal’, Jumping the Queue: Journal of Australian Studies, no 72, 2002, available online at http://www.api-network.com/main/pdf/scholars/jas72_atherton.pdf, viewed 28 October 2010

[8] John Lyons, ‘Foreign buyers silence the Bulletin’, Australian, 25 January 2008, at http://www.news.com.au/national/foreign-buyers-silence-the-bulletin/story-e6frfkvr-1111115393821, viewed 26 August 2010.’

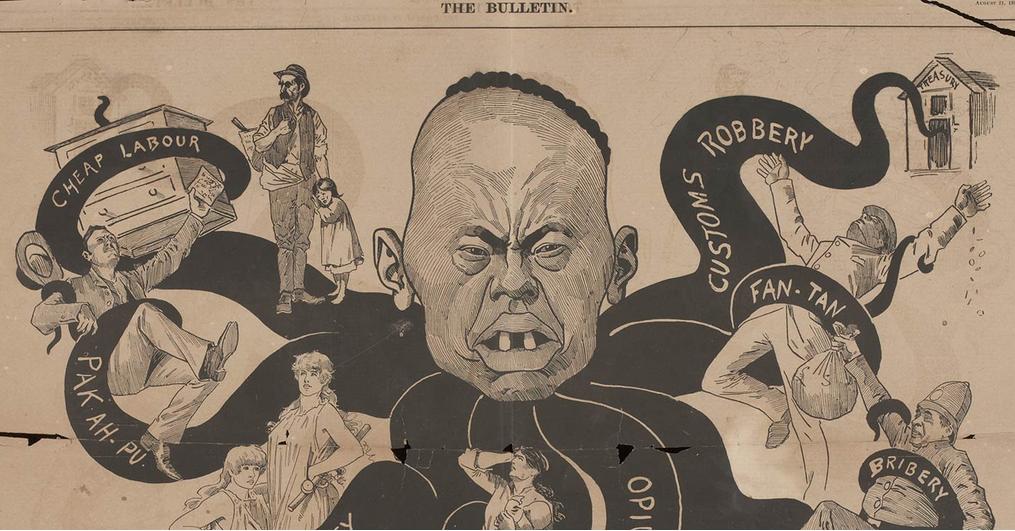

Cartoon titled ‘The Mongolian Octopus’, The Bulletin, 21 August 1886.

Cartoon titled ‘The Mongolian Octopus’, The Bulletin, 21 August 1886.

Defining Moments – ‘1880: The Bulletin established’

by The National Museum of Australia, Canberra. https://www.nma.gov.au/defining-moments/resources/the-bulletin

With its first issue published in January 1880 and its last in 2008, The Bulletin remains one of Australia’s longest-running magazines.

In its early heyday, the weekly publication became known as the ‘Bushman’s Bible’, printing specifically Australian and often controversial material. Many well-known Australian writers and artists contributed to The Bulletin, including Henry Lawson, Banjo Patterson, Miles Franklin and Norman Lindsay.

A revival in the early 1960s saw the magazine turn to more inclusive political and news-based journalism.

Today we send broadcast throughout the colonies the first number of THE BULLETIN … The aim of the proprietors is to establish a journal which cannot be beaten — excellent in the illustrations which embellish its pages and unsurpassed in the vigor [sic], freshness and geniality of its literary contributions. To this end the services of the best men of the realms of pen and pencil in the colony have been secured and, fair support conceded, THE BULLETIN will assuredly become the very best and most interesting newspaper published in Australia.

In its early years The Bulletin operated under the masthead ‘Australia for the white man’ and was widely known for its controversial content. The magazine included criticisms of Britain and other foreign nations, attacks on conservative governments and, after 1886, increasingly Australian-focused material contributed by the public.

At its early peak the magazine had a circulation of about 80,000.

Under the guidance of J.F. Archibald, The Bulletin helped to establish the careers of many of Australia’s key literary and artistic figures. It published stories and illustrations by Henry Lawson, Banjo Patterson, Miles Franklin, Breaker Morant and Norman Lindsay (among others), and was informally known as the ‘Bulletin school of literature’.

Archibald continued to be a patron of Australian arts during his lifetime, and left money in his will for the establishment of an annual prize for portraiture. The Archibald Portrait Prize was first awarded in 1921.

Described as ‘the bushman’s bible’, The Bulletin also provided a platform for the development of uniquely Australian writing, such as the iconic bush ballad.

This early support of a distinctly Australian style helped to create a sense of national pride in opposition to the British focus of many papers of the time. Norman Lindsay, in his book Bohemians of the Bulletin, said, “The Bulletin initiated an amazed discovery that Australia was ‘home’, and that was the anvil on which Archibald hammered out the rough substance of the national ego”.

After suffering a nervous breakdown in 1907, Archibald gave up control of The Bulletin and, under a string of new editors, the paper became increasingly conservative. This led to a considerable drop in circulation and a long period of unpopularity.

Read a former writer to The Bulletin’s account: ‘The Bushman’s Bible: The History of The Bulletin‘ which was published in The Bulletin magazine 1st February 2005.

The Bulletin Magazine Axed

24 Jan 2008, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2008-01-24/the-bulletin-magazine-axed/1022254

The Bulletin’s last cover, 29 January 2008. Bauer Media

‘Australia’s longest running magazine, The Bulletin, is closing down after almost 130 years of publishing.

The owner, Australian Consolidated Press, has announced that The Bulletin will cease publication immediately. A statement from ACP Magazines’ chief executive Scott Lorson attributed a drop in circulation of the magazine to the impact of expanding online coverage of news and current affairs.

Unfit to Lead: The man who destroyed The Bulletin, James Packer, March 2018 goes out for a smoke from The Pavilion at McLaren (psychiatric) Hospital in Belmont, Boston, USA.

Unfit to Lead: The man who destroyed The Bulletin, James Packer, March 2018 goes out for a smoke from The Pavilion at McLaren (psychiatric) Hospital in Belmont, Boston, USA.

Mr Lorson said it was a “sad day” for all involved.

“We have invested heavily in the title with top editorial, photographic and design staff who have been devoted to making The Bulletin the best of its genre,” he said. “However, despite our best efforts, the magazine has simply not been commercially viable for some time. With limited prospects for improvement, the time has come to make a very tough decision.”

ACP says its most recent Audit Bureau of Circulations figures showed The Bulletin selling 57,039 copies in September, down from circulation highs of over 100,000 in the mid 1990s.

Media analyst Harold Mitchell said The Bulletin failed to modernise to compete with the internet.

“Its a great shame that a way couldn’t be found to keep this part of Australia modern and a part of our lives,” he said. “Kerry Packer I am sure would not have axed The Bulletin. He was an Australian through to the core. Now this is private equity. Money speaks many languages, but mostly it’s the bottom line.”

The Opposition’s treasury spokesman Malcolm Turnbull was a former columnist with The Bulletin. He has told Sky television that he is very sad to see it closed.

“Kerry Packer kept The Bulletin going for a lot longer than probably economically he ought to have done,” he said.

“It had been losing money for a long time. It was always very difficult, even back 30 years ago when I worked at The Bulletin, to be able to compete with electronic news media and of course daily newspapers.”

Early Years

The magazine was founded by two Sydney journalists, JF Archibald and John Haynes, in 1880.

It published cartoons, poetry, and short stories sent in by readers and over the years well-known Australian authors like Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Bernard O’Dowd and Miles Franklin all had work appear in the magazine.

Initially the magazine’s editorial focus was to be a journal of political and business commentary, with some literary content.

The paper’s masthead slogan at the time was “Australia for the White Man”.

When Mr Archibald retired in 1907, the publication steadliy abandoned its earlier radical stances on issues like republicanism and became more conservative.

The magazine had its next major shake-up in 1961 when Sir Frank Packer bought it up, sacking many of the editorial staff and ditching the ‘White Australia’ masthead.

In recent years it had again regained its position as a respected source of current affairs and political news and commentary.’