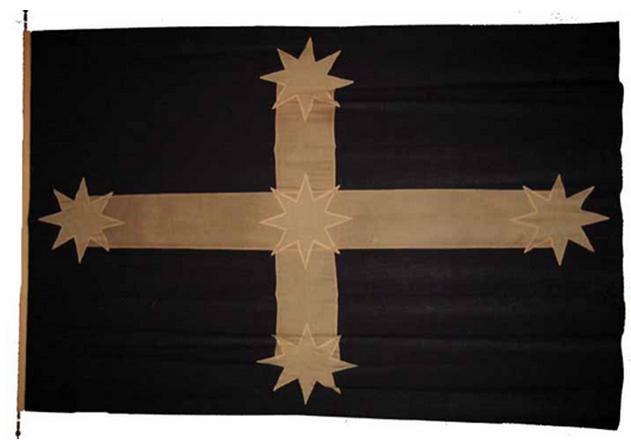

There is no controversy about the Eureka Flag.

It is singularly an icon of Australian nationalism since 1854, symbolic of Australian national identity, Australian sovereign independence and of Australian individual freedoms.

The Banner of the Ballaarat Reform League of Diggers

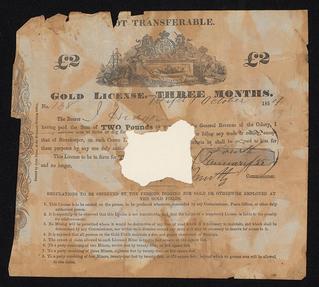

Upon the discovery of payable gold around Ballarat in 1851 as part of Australia’s Gold Rush Era, conditions on the goldfields soon became very harsh.

The gold mining ‘Diggers’ endured ‘obnoxious’ mining licence fees, were forced to pay for overpriced equipment, and were subjected to frequent surprise checks of their mining licenses by corrupt and brutal ex-convict police, all of which increased dissatisfaction and unrest.

Gold prospecting licences rose to 30 shillings a month, which was a lot of money at the time. By 1854, the fee had escalated to 40 shillings or two pounds, equivalent to an average month’s wage at the time.

Irrespective of whether prospecting Diggers were lucky enough to find gold or not, each was required to pay the licensing fee up front upon arrival on a Victorian gold field. This compared with squatters who paid 10 pounds a year yet received a land title to about 100,000 acres. Squatters had rights. They could vote and basically controlled the legislative council in Melbourne. But Diggers had no such rights.

In September 1853, only 400 of the 14,000 Diggers were renewing their licences. The Diggers were divided between those who wanted to take action through constitutional means and those who favoured physical resistance.

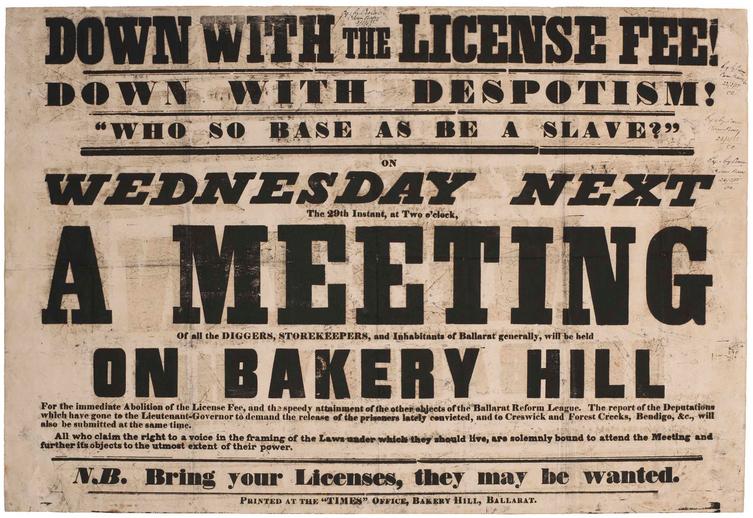

Arising from the unrest the Ballaarat Reform League was created. The League was formed by Ballarat miners to protest against the gold licence, the frequency of licence hunts, the general treatment of miners by the police and the lack of democratic rights for miners. Its charter sought to overturn some of the oppression and sought suffrage, the right to stand for parliament, equal electorate districts, all of the things that are so plain in our constitution today. The League’s charter remains a document that is the real birth right of our parliamentary democracy because it clearly states the basic democratic political principles.

November 29, 1854:

The Ballaarat Reform League staged a ‘monster meeting’ of around 12000 Diggers was held at Bakery Hill protesting against the government’s exorbitant gold licence which was seen as an unjust tax.

A list of demands was prepared by the Diggers for Victoria’s then colonial Governor Hotham. Fired up by the rallying for political rights, a lot of the Diggers burned their licences.

Peter Lalor’s Bakery Hill Speech

November 30, 1854:

The next morning the government called for another licence check, which enraged the Diggers even further.

Following the provocative licence hunt by police, The League held a second spontaneous protest meeting up on Bakery Hill later that same day in which around 2000 Diggers attended. The Eureka Flag was hoisted by its custodian in The League Henry Charles Ross, a Canadian miner.

The new flag was known at the time as the ‘Digger’s Flag of the Southern Cross‘. After the Eureka Stockade uprising, the flag was subsequently referred to as the Eureka Flag since the uprising took place at the specific Eureka Diggings, of the Ballaarat goldfields, and it was out of respect for the slain Diggers at Eureka. “Eureka” comes from the Ancient Greek word εὕρηκα heúrēka, meaning “I found (it)”. The term had been used on the Californian goldfields since 1848, six years prior, and a number of Diggers had arrived on the Australian goldfields since the Californian gold had been depleted.

Ross hoisted it for the first time up an eighty foot pole taken from nearby Bullarook. The flag itself was huge, measuring 4 by 2.6 metres. It was a strong symbolic statement of desired Australian nationhood.

The flag would have been visible for miles which would have been The League’s intention, and with Ballaarat situated high up on the range it is prone to strong winds, so on Bakery Hill, the Eureka flag would have flow stiffly and commanding.

In the absence of the leader of the Ballarat Reform League, Irish-born Peter Lalor (1827-89) stepped in and delivered his now famous speech calling on Diggers to stand up for their rights and liberties.

Lalor mounted the stump and proclaimed:

“Liberty!

Fellow diggers, outraged at the unaccountable conduct of the Camp officials, in such a wicked license-hunt at the point of the bayonet as the one this morning, we take it as an insult to our manhood and a challenge to the determination come from the monster meeting yesterday. Now I call on you to fall into divisions of eighty men according to your weapons, and to choose your captains from the best men among you. It is my duty now to swear you in, and to take with you the oath to be faithful to the Southern Cross. Now hear me with attention. The man who, after this solemn oath does not stand by our standard, is a coward at heart. I order all persons who do not intend to take the oath to leave the meeting at once. We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other, and fight to defend our rights and liberties.”

“Comrades, assist me to pray for the safety of these men. Bless these men that go to fight for their rights and liberties. May Heaven shield them from danger. I charge you to commit no violence to the peaceably disposed. I will shoot the first man who takes any property from another except arms and ammunition and what is necessary for us to use in our defence. Now fall in comrades, and march behind our standard to the Eureka.”

Lalor’s seminal speech was known as the Bakery Hill Speech and after it, Lalor was designated Commander-in-Chief of the rebellion. The speech was all about oppressed Diggers about to fight to the death for their rights and liberties against British tyranny on the goldfields.

It was a League of the original White self-employed entrepreneurial gold ‘Diggers’. It had nothing to do with workers or unionism or communism or globalism. The entire occasion was singularly Australian nationalist.

The Diggers ‘Oath of the Southern Cross’

Peter Lalor after his speech called on Diggers to form armed divisions of 80 men and be sworn in for action.

Lalor knelt and with his right hand pointing to the Eureka Flag, swore an oath on behalf of the 500 remaining Diggers declaring:

“We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties.”

‘Swearing allegiance to the Southern Cross, 1854′ – Charles A. Doudiet’s watercolour, pen and ink on paper.

‘Swearing allegiance to the Southern Cross, 1854′ – Charles A. Doudiet’s watercolour, pen and ink on paper.

The assembled 500 Diggers repeated the oath kneeling with heads uncovered and pointing to the Eureka Flag.

The Diggers Oath taken under this new flag became a battle cry calling on all to fight for their rights and justice. Lalor reinforced this justification to fight when he brought up the recent acts of the soldiers and licence hunts.

Not only was the speech persuasive, it was also very inspiring. The speech told them about the future rights that they would have if it all went to plan and it inspired people to want and value their freedom even more than they had. The act of raising a new flag of the Southern Cross and of swearing an oath by this flag really constitutes the ritual of rebellion, Australia’s first Digger Uprising. The flag flew as a symbol of their defiance against British tyranny. Many regard it as a moment of the real beginning of a sense of Australian national independence and identity distinct from old world Britain.

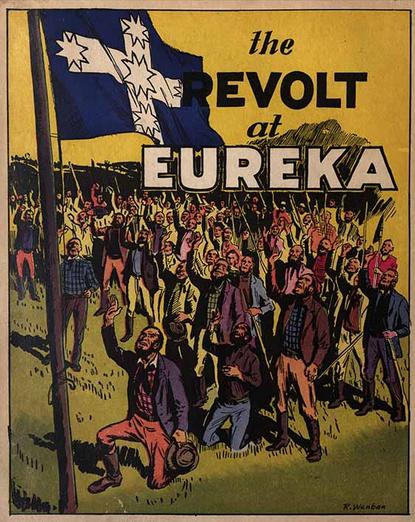

Eureka Stockade

Some 120 Diggers with the flag were led by Lalor directly to the Eureka Diggings site where a rudimentary protest stockade was constructed by the Diggers as defence against the government’s threatening armed forces. They built a rudimentary wooden fort at the Eureka Diggings over December 1 and 2 and took up arms ready to defend.

On Sunday at 4:45am on 3 December, 280 British militia soldiers and police charged the Eureka Stockade whose numbers by dawn had dwindled to around 120 diggers. The police units emulated the militia with a ruthless bayonet charge. About 22 diggers and 6 soldiers were killed in the fight. Rebel Captain Ross fought to the death and was killed defending the flag at the base of the flagpole in the centre of the stockade. Some 140 men were arrested. The authorities chose 13 supposed ring-leaders for trial. They would all be eventually acquitted.

Australia’s First Fallen Diggers

Australia’s First Fallen Diggers

Details of the Eureka Stockade rebellion are best details in Geoff Hocking’s book ‘Eureka Stockade: the events leading up to the attack in the pre-dawn of 3 December 1854’ published in 2004.

The ‘Eureka Stockade’ uprising was essentially a short-lived revolt by gold miners against petty officialdom and harassment by a corrupt Police force, who would often ask miners to show their gold digging licences several times a day. The miners also objected to the high cost of the licences.

After the battle, Police Trooper John King in charge tore down the flag (referred to by authorities as ‘The Diggers Standard’), as it had been reviled by the victorious soldiers and police. The captured rebel flag was taken back to the Government Camp. A report in the Geelong Advertiser told how ‘the diggers’ Standard was carried by in triumph to the Camp, waved about in the air, then pitched from one to another, thrown down and trampled on’. The soldiers were seen dancing around the flag on a pole, ‘now a sadly tattered flag from which souvenir hunters had cut and torn pieces’.

On 4 December 1854 Ballarat Camp clerk S.D.S. Huyghue wrote to his friend Reynell Eveleigh Johns in Bendigo describing the dramatic events in Ballarat and enclosing a tiny blue fragment of the rebels’ flag: “Next morning the policeman who captured the flag exhibited it to the curious and allowed such as so desired to tear off small portions of its ragged end to preserve as souvenirs.”

The flag next appeared in Melbourne as Crown evidence at the Eureka trials in early 1855, when thirteen stockaders were tried for treason and acquitted. At the trial of John Manning, Trooper John King appeared as a Crown witness and he said ‘I took a flag down. This (flag produced) is the flag.’

It appears that nobody claimed the flag after the trials. Two days after the last defendants were found not guilty, Trooper John King resigned from the Victoria Police and took his flag as a trophy. John King became a farmer, eventually settling in the late 1870s near Minyip in the Victorian Wimmera district. Here the flag made occasional appearances at country bazaars.

What remained of the flag was kept by the King family and first loaned and later deeded to the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery. Labor’s current member for Ballaarat, Catherine King MP these days stills hate the flag and is keen to usurp it for anti-Australian Communist misinformation.

Eureka Flag Design Origins

The major motif of the flag was the Southern Cross group of five stars. Since the stars are visible only in the southern hemisphere, the use of the Southern Cross in the flag and in the miners’ oath may symbolise a rejection of the Old World and its oppressive practices. The bands may stand for the miners’ unity and the background may represent their blue shirts.

The white cross behind the stars has Christian crusader origins from Medieval Europe.

The Crusader’s Cross was worn by European soldiers during the Crusades to protect Christian Jerusalem against the Islamic Byzantine emperor and his marauding Turks. In 1095, Pope Urban II called for a crusade against the Muslims to regain control of Jerusalem. European Christian nobles and yeomen heeded the call. The Crusade became the first of many and persists to this day.

But then The Crux was derived from ancient Celtic pagan origins. The Crux is derived from the ancient pagan four-spoked Celtic Sun Cross.

The four fold “Celtic Cross” symbol was used as a magical talisman by so many cultures because it illustrates the power of the Five Elements and the four cardinal directions. The person who could command and control these forces was indeed invincible and victorious.

The Five Elements are: Expanding (Ether), Contracting (Air), Rising (Fire), Descending (Water), and Centering (Earth). According to Celtic pagan lore, the Centre embodies the final stage in the manifestation of Life Force as it is drawn into the Earth through the power of Gravity.

How coincidently the five stars in the Eureka Flag approximates the Celtic Cross, but then most Digger rebels at Eureka were of Irish descent.

The Southern Cross Symbol

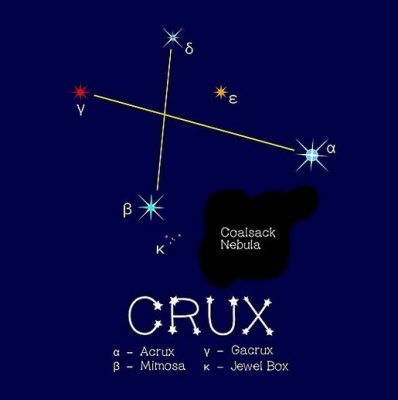

The Eureka Flag’s white five-star cross is representative of the Southern Cross Crux constellation visible in a clear southern sky at night most prominently over Australia.. The flag stylises the shape of a white Christian cross (not saltire) in front of a navy blue field background.

Greek mythology of 2500 years ago told of a five-star Southern Cross visible from the northern hemisphere, apparently astronomical owing to the phenomenon of the precession of equinoxes. The Southern Cross later featured in literature as early as 1320, when the Italian writer Dante, a scholar of the Greco-Roman classics, mentioned it in his work: The Paradisio-Inferno-Purgatorio trilogy. To the four brightest stars of this Southern Cross, Dante in his work, attributed the admirable virtues of Justice, Prudence, Temperance and Fortitude.

So the Southern Cross has for centuries taken on a mythical significance for Europeans and then especially the early seafaring explorers during the Euopean Age of Discovery from the 16th Century. In 1502, Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci recorded having seen “four magnificent stars”. In 1515, Italian explorer Antonio Pigafetta, who sailed with Ferdinand Magellan on mankind’s first voyage around the world, wrote of “a wonderful cross, most glorious of all the constellations in the heavens”.

The cross was finally defined as a separate constellation in 1679 when French astronomer Augustine Royer first coined the term in Latin: ‘Crux Australis’ (‘The Southern Cross’).

All five stars have been named traditionally in Greek. The brightest star is Alpha Crucis and is really a triple star. It is blue-white. Second brightest is blue-white Beta Crucis (Mimosa) which forms the eastern tip of the upright cross. Third brightest is Gamma Crucis at the top of the cross having a distinct red-orange star when viewed by telescope. Delta Crucis is the faintest of the four stars making up the cross. Like Beta Crucis, it is a blue-white giant star. The faint fifth star, Epsilon Crucis, shows up as a dusty orange colour below and just to the left of Delta Crucis.

Southern Cross Significance to Australia

The Southern Cross is the best known and most represented star group in the Southern Hemisphere. The group’s distinctive shape is easily located because of its brightness and close proximity to each other. It can be seen all year round from almost anywhere in the Australia. The constellation is no longer visible in the northern hemisphere. So the Crux is unique to the southern hemisphere, and so to those in the Antipodes (means ‘other side of the planet from Britain’, aka Australia) and so is considered distinctly different to being back in Britain and Europe, thus special to Australia and to colonists at the time.

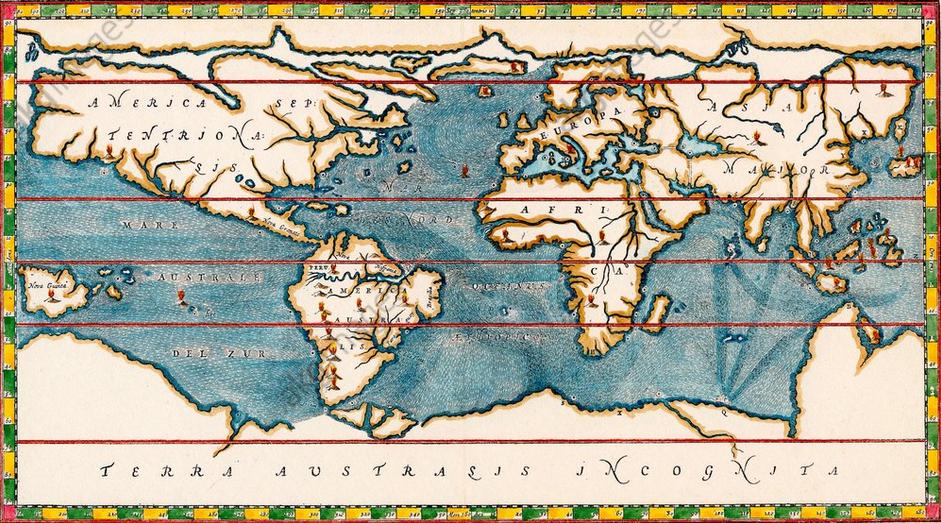

Since European antiquity of the 2nd century, legend prevailed of an ‘unknown southern land‘ (Latin: ‘terra australis incognita‘), in which ‘australia’ means ‘south’.

Unknown knowns until Cook’s discovery of the habitable East Coast in 1770

That Italy’s most famous writer should name the stars, continues the remarkable multicultural history of The Eureka Flag _ Eureka being Greek for the exclamation “I have found it!”.

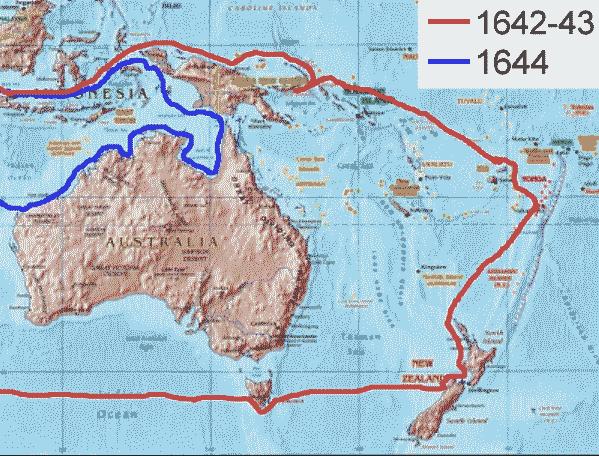

The name New Holland was then first applied to western and north coast of Australia in 1644 by the Dutch seafaring explorer Abel Tasman on his second voyage. The coastline he navigated appeared desolate, so it was dismissed as unsuitable for settlement, else we’d be speaking Dutch. Tasman had completely missed the continent on his first voyage of 1642-43.

After British explorer James Cook discovered the continent’s east coast in 1770, it was no long ‘incognita’ (unknown). British navigator Matthew Flinders first Anglicised the Latin ‘terra australis’ to ‘Australia’ following the first circumnavigation, in his in his mapping and correspondence of back to England in 1804. Flinders used the name AUSTRALIA (all capitals) for the map title.

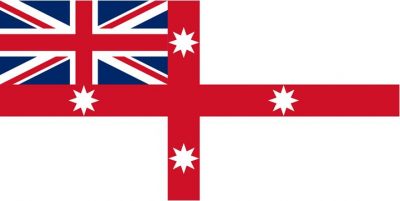

The Eureka Flag’s the logo adopted during Australia’s then colonial Gold Rush period by the Ballaarat Reform League of gold ‘Diggers’ in 1853, apparently designed by one Digger Henry Ross, a Canadian migrant. The Eureka Flag design was modelled on the New South Wales Ensign of the 1830s, since at the time the continent had been divided into several British colonies.

The key difference of the Eureka Flag and the New South Wales Ensign was the deliberate exclusion of the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the canton. (Canton? A rectangular area at the top hoist corner of a flag, occupying up to a quarter of the flag’s area). The white field background was inspired by the White Ensign of the British Royal Navy.

This colonial nationalist flag featured the five eight-pointed stars of The Great Southern Cross

In turn, the 1830s New South Wales Ensign had been based upon The National Colonial Flag for Australia of 1823, which was the first recorded attempt to design a distinctive national flag for a future Australia nation. The flag featured the stylised Southern Cross with the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain in the canton. The white field background had been inspired by the White Ensign of the British Royal Navy.

This early colonial nationalist flag featured the Royal Marine red St George Cross and only four eight-pointed stars in the formation of The Great Southern Cross

According to Frank Cayley′s book Flag of Stars the flag′s five stars represent the Southern Cross and the white cross joining the stars represents unity in defiance. The blue background is believed to represent the blue shirts worn by many of the diggers, rather than represent the sky as is commonly thought.

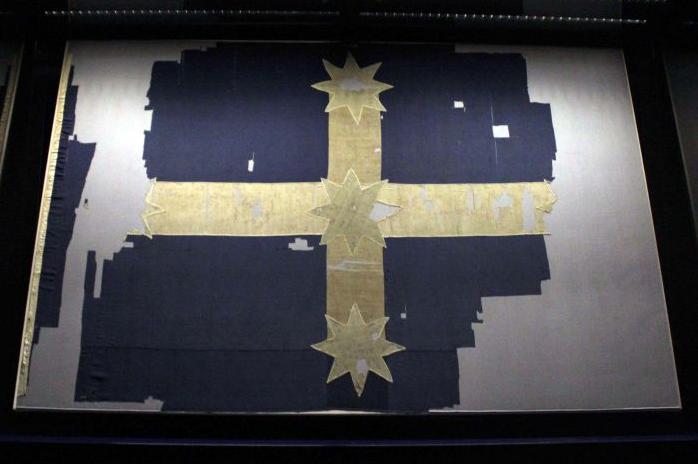

The flag above is considered to be the Eureka Flag (a number of variants seem to have existed), as it is the design of the flag torn down at the stockade by Police Constable John King on the morning of the miners′ uprising – Sunday, 3 December 1854. The torn and tattered remains of this flag is kept at the Ballaarat Fine Art Museum, in Ballaarat.

Led by Peter Lalor, who later became a respected Victorian MP and Minister, the Eureka uprising was a spectacular failure in a military sense. The revolt had its roots in the killing of a miner, James Scobie, by a publican. An inquest was held, but despite the evidence of miners, no conclusion was made about who was responsible. Instead, the miners who pressed for the arrest of the publican were taken into custody.

This sparked protests by the miners who held many public meetings, and sought to take the law into their own hands by seeking out the publican and burning down his hotel. When the culprits were arrested and imprisoned, the situation in the goldfields became explosive and expanded to cover general discontent with unequal laws and unequal rights.

The miners elected Lalor to lead them, and they built a stockade at the goldfields to defy the authorities. It was at this time the Eureka flag first appeared. Within a few days, a military force of about 300 men had assembled to attack the Stockade, and within 15 minutes of the commencement of the attack, had smashed the stockade and killed many of the rebels.

The Eureka Flag Crafting

The original Eureka Flag of 1854 was 4.0 x 2.6 metres and has become an Australian national icon.

The flag comprises 13 pieces of navy blue calico for the background, 4 pieces of white cotton twill for the cross, and 5 pieces of fine white cotton ‘petticoat’ lawn for the five eight-pointed stars, representing the Southern Cross (Crux constellation).

The original Eureka Flag was huge (4.0 m by 2.6 m) but hateful cutting up and souveniring of it by the British saw it lose a third of its length. After the Diggers’ Rebellion against British tyranny at Eureka Stockade, parts of the flag got cut up and ‘souvenired’. The flag was ultimately recovered by with only 60% of the original flag intact.

The design of the Eureka Flag was initially designed as a banner for the Ballarat Reform League some time after the League’s first meeting on 11 November 1854. The use of banners and flags was important at the time for sending a visual message about a group’s aims.

The flag was designed by the miners themselves, either by a group of miners or by a Canadian miner, Henry (Charles) Ross. Although there were former flag-makers digging on the Ballarat gold fields, the flag was almost certainly made by women, probably the wives of miners involved. There is an oral family tradition that three women, including one named Anastasia Withers, worked on the flag. The flag’s proportions were unusual with a ration of 20 to 13, which compares with most flags that are 2 to 1. The makers of the flag left behind a mark similar to the initial ‘W’ on the fly end of the flag.

Australia’s Nationalist Symbol

The “Crux Australia” (Eureka Flag) became the symbol of The Reform League. The Diggers’ demands were for a fair go, justice and democratic rights to be recognised as citizens. The Leagues demands included the abolition of the license and gold commission, the vote for all males and representatives on the legislative council.

Peter Lalor led the rebellion that is most commonly known as the Eureka Stockade, and the birthplace of Australian Democracy. Even though the battle was lost, the war for greater equality for the miners was soon won. Although the Stockade failed to achieve its objective, it did gain the attention of the Government and lead to significant Government reforms including replacing the miner’s licenses with an affordable annual miner’s licence.

Within a few months, the miners elected Lalor as a member of parliament for Ballarat, which was one of the things they had been fighting for – political representation.

The Eureka Flag design has since achieved national adoption into the culture of a new independent Australian nation as a symbol of democracy, protest and a wide variety of other causes. That’s appropriate, so long as the use of the flag flying causes are uniquely Australia and not globalist to undermine Australian national identity, sovereign independence or individual freedom. For this joint nationalist cause was what the original Diggers of the Ballaarat gold diggings fought and sacrificed for.

The Eureka Flag is Australia’s enduring nationalist symbol.