Why did American President Donald Trump select Singapore to meet North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un on June 12, 2018?

Convenience, security, First World, trust?

Why did China summon Kim to Beijing for a secret meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in late March 2018? This is the first time Kim has set foot outside North Korea since he took power in 2011.

Fat Chinese Puppet

Why did Kim Jong-un meet Xi Jinping in second surprise visit to China in May 2018 weeks out from the North Korean leader’s inaugural diplomatic meeting President Trump?

Why did Kim Jong-un meet again with Xi Jinping in Beijing on June 19, a week after meeting Trump?

Chinese state TV did not say what the two leaders had talked about.

China has been angling to retain its influence over its ally amid the recent rapprochement between North and South Korea, and Kim’s desire to directly engage with the US. Kim and Xi have had a frosty relationship since Kim came to power in 2011, only meeting for the first time in late March. That was Kim’s first official trip outside North Korea when he travelled to Beijing in a bullet-proof train.

“China is willing to continue to work with all relevant parties and play an active role in comprehensively advancing the process of peaceful resolution of the peninsula issue through dialogue, and realising long-term peace and stability in the region,” Xi said.

The meeting between the two men comes as the Chinese premier, Li Keqiang, is set to travel to Tokyo for meetings with the Japanese prime minister, Shinzō Abe, and the South Korean president, Moon Jae-in.

Why did American President Donald Trump select Singapore to meet North Korea’s Kim Jong-Un?

Malays hate the Chinese.

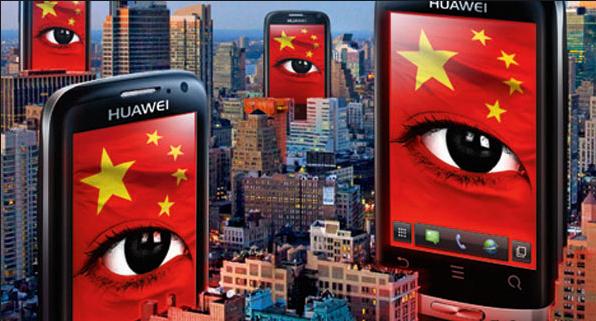

Singapore is among the five Asian countries most vulnerable to cyberattacks, according to a new report released this week by global consulting firm Deloitte.

According to the company’s annual Asia-Pacific Defense Outlook, Singapore, along with Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea – dubbed the “Cyber Five” – are judged to be nine times more vulnerable to cyberattacks relative to their larger Asian counterparts China and India. Among the Cyber Five, South Korea topped the list with a cyber vulnerability score of 884 (compared to 329 in 2008), with Singapore scoring 399 (compared to 224 in 2008).

The report’s conclusions are based on a Cyber Vulnerability Index designed by Deloitte, which measures how extensively each economy relies on Internet-based interactions. According to the firm, the data was based on compiled historical data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators, which allowed it to gauge metrics such as countries’ rate of cellphone subscribers, secure Internet servers, fixed broadband subscribers, and rate of Internet usage. The index, Deloitte admitted, does not include other key indicators of vulnerability, including the level of security and countermeasures in place and the number of military and government systems exposed to the internet.

The wide gap in cyber vulnerability between the Cyber Five and other Asia-Pacific countries could pose a future challenge for cyber defense and offense, Deloitte said. For example, lower vulnerability nations like China and India may calculate that they can afford to be more aggressive in cyberspace because they believe their rivals will suffer relatively more damage from cyberattacks than they might.

“The lower-vulnerability nations may therefore by prepared to behave more aggressively in cyberspace, because their potential adversaries are much more exposed to Internet-based damage,” the report said.

As for the Cyber Five, the report argued that these nations would have to rely on policies that extend beyond just collaborative approaches or tit-for-tat retaliation in cyberspace that might work either for less vulnerable or less-advanced economies who would suffer less Internet-based damage. A more diverse policy mix, with more varied tools such as economic sanctions or other trade measures applied disproportionately or unpredictably, may be required for these countries to defend themselves.

“Threatening disproportionate or unpredictable retaliation for cyberattacks, including responses outside cyberspace, for example, trade measures or other economic sanctions, may be essential elements of a rational cyber policy for the highly-vulnerable Cyber Five,” the report said.

Why is Singapore the top destination for Chinese firms looking to expand overseas?

Top Chinese companies like Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent often look to overseas ventures, and Singapore is at the top of the lists they consider, a report by Professional services firm JLL has found in April 2018. It’s because imperial China is imperialist and due to the strong links to China and its geographical location, Singapore is the most connected city in the world to China, followed closely by New York and Sydney.

When China wants to disarm (attack) Australia, Beijing knows that its cyber attack via Singapore would be like water flowing downstream.

- Huawei

- DBS Group

- OCBC Bank

- UOB

- Baidu

- Alibaba

- Tencent

- Singtel (Optus)

- HK Central United Overseas Bank

- Wilmar International

According to researcher at the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre at The Australian National University, Adam Ni, China is in the advanced stages of developing a superweapon that can devastate targets at great distances.

Photos circulated on Chinese social media show what is suspected to be an experimental electromagnetic railgun mounted on the bow of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy landing ship Haiyang Shan.

At the 19th Chinese Communist Party Congress in October 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for the PLA to be completely modernised by 2035 and to achieve ‘world-class’ status by the middle of the 21st century. China is supporting this ambition by developing a variety of ‘game changer’ military technologies, including hypersonic vehicles, anti-satellite capabilities and artificial intelligence-equipped weapons.

A key guiding concept for China’s military modernisation is ‘revitalising the military through technology’, which involves the development of a self-sufficient defence industry. Past efforts at this have struggled because China’s defence industry was inefficient, poorly managed, rigid and unable to fill the requirements of the PLA.

But this has changed over the last two decades due to expanding defence budgets, technological acquisitions and a raft of reforms that focus on making the sector more competitive. China now has the ability to develop advanced fighters, aircraft carriers, new-generation intercontinental ballistic missiles, drones and other advanced platforms. Another indicator of this progress is China’s booming arms exports, which rose 74 per cent from a global share of 3.8 per cent in 2007–11 to 6.2 per cent in 2012–16. While China is still far behind the world’s leading arms exporters (the United States and Russia), it is catching up fast.

Since 2013, China’s defence industry has been subjected to a series of reforms and initiatives that include new guidelines and plans, innovative institutional arrangements and a renewed focus on civil–military relations.

In recent years, Xi has intensified civil–military integration efforts to leverage civilian expertise in accelerating military modernisation. An important goal of this effort is to make it easier for private companies to work on defence projects. In March 2015, Xi announced the elevation of civil–military integration to national strategy, which highlights its importance for military and economic development. He further underscored this by creating the powerful Central Commission for Integrated Military and Civilian Development to provide high-level guidance and oversight. State agencies, such as the State Administration for Science, Technology and Industry for National Defense, continue to do the bulk of the implementation work.

The Central Commission’s most important strategy document for the defence industry is the 13th Defence Science and Technology and Industry Five-Year Plan (2016–2020). It calls for streamlining and targeting investment across core areas, accelerating weapons development, raising arms exports and promoting collaboration between military and civilian organisations.

Another key initiative is the 2025 Defence Science and Technology Industry Plan, which calls for the upgrade of China’s defence science and technology base. This is in line with the Made in China 2025 strategy — a sweeping initiative to overhaul China’s manufacturing industry.

Moreover, China outlined a list of sixteen megaprojects in the Medium- and Long-term Science and Technology Development Plan (2006-2020). These include advanced numeric-controlled machinery, high-end generic chips, integrated circuit manufacturing and techniques, high-definition earth observation systems, advanced nuclear reactors, manned aerospace and moon exploration, and large aircraft. These projects involve numerous companies and research institutions from China’s sprawling defence industry. Technologies developed for every one of these megaprojects would have important military applications in addition to civilian uses.

But despite maturing rapidly over the last two decades, China’s defence industry continues to be plagued by notable weaknesses such as outdated management models, weak governance, corruption, inflexibility and monopoly power. These weaknesses will need to be addressed if the industry is to better support PLA modernisation in the years ahead.

China’s defence industry has matured considerably since the 1990s and China is now poised to shift from a follower to a leader in defence innovation despite several weaknesses. The industry’s ability to develop and produce high-quality equipment and cutting-edge weapons for the PLA will be key to China’s continuing rise as a military power.

Source: February 24, 2018, by Adam Ni, ANU

http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/02/24/superweaponising-chinas-defence-industry/

Wake Up Canberra!