Not political, just factual – Aborigines didn’t approve of British Colonisation. From 1788-1934, 146 turbulent years involving ongoing frontier battles took place across the continent between Aborigines and mainly British settlers. The main conflicts are officially documented.

The fact is that military might and international law at the time resulted in British Colonisation winning legal sovereignty over Australia. The Aborigines lost the war.

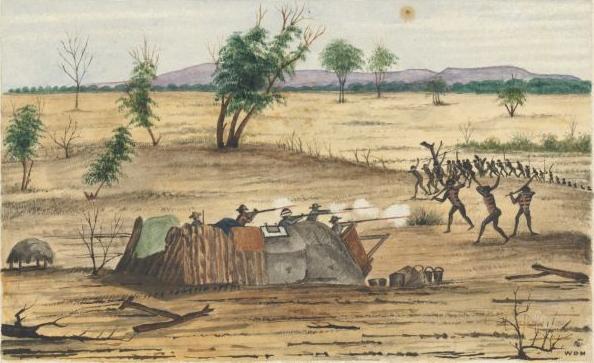

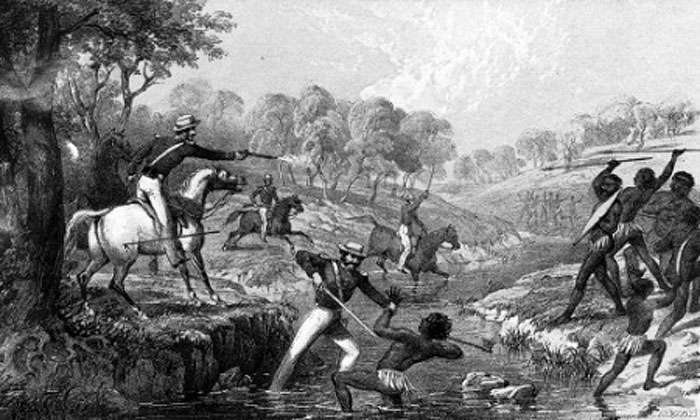

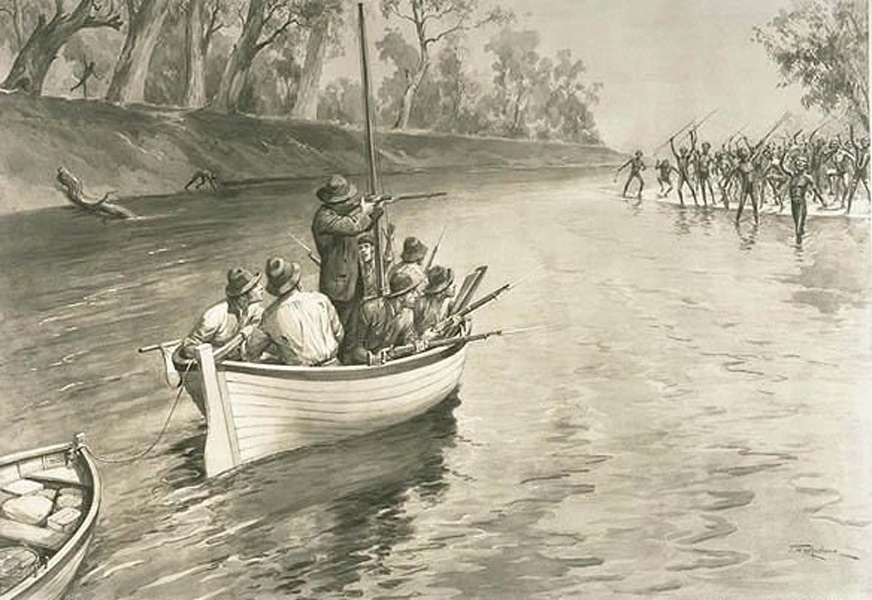

Colonisation of Australia included sporadic tribal raids upon settlers followed up by reprisals or ‘punitive expeditions‘ or ‘dispersals‘. It was a bloody and widespread conflict; effectively a protracted colonial war spanning 146 years or five generations characterised by hundreds of violent Aboriginal raids and officially-sanctioned massacres.

It began from first settlement around Sydney Cove in May 1788 (just four months after the First Fleet arrived) once British Colonisation were observed clearing land and catching fish around the harbour, warriors of the local Cadigal tribe speared five convicts. Two years later in September 1790, colonial Governor Arthur Phillip was himself speared in the shoulder at Manly Cove. Punitive expeditions by the colonists started in December 1790 after Phillip’s huntsman was killed by Aboriginal warrior, Pemulwu.

The last known punitive expedition condoned by the government was in 1928 at remote Coniston (cattle) Station in the Northern Territory, when a police posse killed up to 110 Aborigines. The year 1934, just three generations ago, was probably the last episode of Aboriginal-White reprisal killings. The last episode was known as the Caledon Bay Crisis in north-east Arnhem Land.

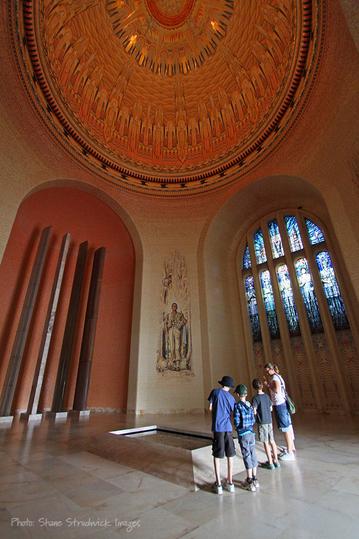

In The Great War (1914-1918) about 60,000 Australians were killed. In World War II 27,073 Australians were killed, in Korea 339 Australians were killed, in Vietnam 521 Australians were killed, and more Aussies have been killed in conflicts since. Many more have been wounded and suffered trauma through the rest of their lives and our current veterans are no different. Many war dead were never found.

The Australian War Memorial recognises these conflicts and others involving Australians, including rightly special recognition of the war dead never found – by the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

‘The Killing Times’

By comparison, the Australian Frontier War (1788-1934) has historical anecdotal conservative estimates of 20,000 Aborigines killed and 2,500 Whites killed.

The scale and brutality were not insignificant. That these killings occurred is not disputed; only the numbers. But how many have to be killed on Australian soil for a conflict to be deemed a war and for that war to be recognised as a ‘proper war’ by the Canberran bureaucracy?

Tribal raid by Aborigines on settlers was followed by reprisal posses, some officially sanctioned by the government (military or police), others by settlers themselves. Few were prosecuted.

Early fighting in the colony included the Appin Massacre of 1816, Bathurst Massacre of 1824, the Myall Creek Massacre of 1838 and the Slaughterhouse Creek Massacre of 1838. This latter incident was ordered by the acting Lieutenant Governor of New South Wales Colonel Kenneth Snodgrass dispatching mounted police who attacked an encampment of about 120 Kamilaroi people.

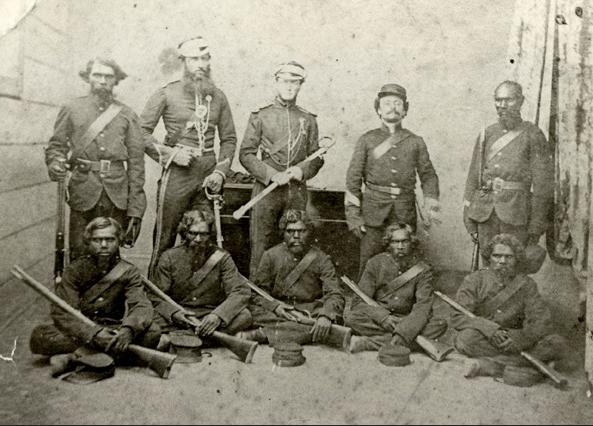

1848 – Queensland’s Native Police Force key participants in the Australian Frontier War

1848 – Queensland’s Native Police Force key participants in the Australian Frontier War

Australian History invisible to the Australian War Memorial in Canberra

Other massacres and their respective casualties:

- 1828–1832 The Black War in Van Diemen’s Land – the killing of more than 2500 Aborigines across the entire island, starting with Cape Grim (42 Pennemukeer)

- 1830 north of Fremantle the first official ‘punishment raid’ on Aborigines in WA led by Captain Irwin

- 1833–34. Convincing Ground near Portland (200 Gunditjmara)

- 1841 at Rufus River (30-40)

- 1842 at Evans Head (100 Bundjalung)

- 1840-50 – the Gippsland massacres (up to 1000, including 150 at Warrigal Creek in 1843)

- 1890–1926 ten mass killings of Aborigines across the East Kimberleys by a quarter of Western Australia’s police force as payback for attacks on livestock

- 1861 at Nogoa River police and settlers killed 170 in reprisal for the Aboriginal killing of the Wills family

- 1867 at Goulbolba Hill a posse of 100 whites killed 300 Aborigines – men,women and children

- 1872 at Skull Hole over 200 Aborigines killed by police

- 1879 at Selwyn Range 300 Aborigines shot by police and settlers in reprisal for the killing of squatter Bernard Molvo and his men

- 1884 at Battle Mountain (near Mount Isa) 200 Kalkadoon people killed

- and many others.

The exact numbers of Australians (Aboriginal or otherwise) wounded, displaced, died of famine or disease during this 146-year colonial conflict are unknown. Many war dead were never found, especially on the Aboriginal side. Non-battle casualties (not K.I.A.) are often lesser reported casualties of war. Records back then were not kept in the main. Yet this does not discard nor diminish the significance of the conflict, the human lives lost on both sides.

But Australian War Memorial says: ‘Best We Forget’

It was Australia’s first war no less and thousands tragically died on both sides, yet the Council of the Memorial chooses to ignore all 24,500 plus dead Australians killed as part of a colonial conflict war in early Australia. It’s historical revisionism as if the conflict never happened, doesn’t matter, is outside some arbitrary definition of a ‘proper war’ and the dead never existed and don’t matter. Tell that to the descendants, Dr Brendon Nelson, Director of the Australian War Memorial in pompous Canberra.

Brendon Nelson’s literal interpretation of Charles Bean’s definition of war constitutes a prejudiced denial of Australian history – unjust and dark as it is. Brendon has made the AWM his replacement fiefdom. At least his predecessor was a military man, not a failed polly needing relevance.

So, what is the function of the Australian War Memorial?

“The mission of the AWM is to assist Australians to remember, interpret and understand the Australian experience of war and its enduring impact on Australian society. (AWM About the AWM) If indigenous people are Australian and if they have been subjected to war or warlike operations, this experience is part of that mission. The 1980 Act does not prevent this. Definitions of the Defence Force include those raised in Australia before the establishment of the Commonwealth i.e. colonial conflicts. (section 3) In Section 6 “Powers”, the AWM is to provide facilities to stimulate interest in Australian Military History. (Section 6 (2) g) With estimates of over 20,000 Europeans and Aboriginals killed, the “Frontier Wars” would be the bloodiest warlike conflict within Australia’s current borders. (estimated deaths from AWM War History Colonial Period).”

– Tony Peterson, Sun 22 Dec 2013.

“Last year I, along with many others, signed a petition through “Change” seeking to have the names of Peace keepers who had died on duty recorded in the AWM. This was eventually successful – even though the act had to be amended to allow this. Why can’t another amendment be made? Why does this “Conspiracy of Silence” have to continue??? Given the large number of school students who visit the AWM, what a wonderful opportunity it would be for them to learn about the “Forgotten Wars” – fought here in Australia.”

– Helen Carrick, Tue 4 Feb 2014

Of course all war is wrong, but if it is forgotten, if we ignore sacrifice then what do we take from it in memory and what do our children learn or risk repeating?

Failed political leader Brendon has come up against this oft raised issue previously. His education and knowledge is framed around economics, medicine and politics; not social or cultural history. Joining the Liberals, he was promoted as far as the Education the Defence ministerial portfolios – following PM John Howard’s orders. But then he failed to lead the party because he was not a leader.

Brendon follows orders and institutional expectations and makes a good manager running the Australian War Memorial in Canbrerra. Respect for Australians who fell on both sides (Aboriginal and White) during Australia’s very own colonial war on home soil, is a brave leadership decision, a national cultural issue beyond Brendon.

In 2013, Brendon narrowly hid behind Charles Bean’s 1941 interpretation of the memorial restricted to “honouring the services of the men and women of Australia’s military forces deployed on operations overseas on behalf of the nation.” Brendon is an orthodox disciple of Bean.

Well, Charles Bean’s Old Definition of War excludes conflicts that those born in Australia have participated in before Australia was declared a “nation” in 1901. So Brendon are ya gunna rip out all recognition of the 16,000 of our forebears who fought for the King in Britain’s Boer War (1899 up until December 31st 1900)?

Charles Bean’s Old Definition of War also excludes any Australian who participated in any conflict who was a member of Australia’s military forces. So Brendon are ya gunna rip out all recognition of all the unsung heroes, the thousands of nurses and doctors not enlisted as combatants – like the Bluebirds, or the Fuzzy Wuzzies along Kakoda, or Kapiu Gagai or the Home Front?

Charles Bean’s Old Definition of War also excludes any Australian who participated in any latter ‘peacekeeping mission’, since it technically is not a “conflict”. So Brendon are ya gunna rip out all recognition of Australia’s peacekeeping involvements from the AWM?

This includes Australians peacekeeping missions in Indonesia (1947–51), Kashmir (1950–85), Korea (1953–Present), Israel – under Operation Paladin (1956–Present), Congo (1960–61), West New Guinea (1962–63), Yemen (1963), Cyprus (1964–Present), India/Pakistan Border (1965–66), Sinai – under Operation Mazurka (1976–79) (1982–86) (1993–Present), Israel/Syria Border (1974), Lebanon (1978), Zimbabwe (1979–80), Uganda (1982–84), Iran (1988–90), Thailand/Cambodia Border (1989–93), Namibia – under UNTAG (1989–90), Afghanistan (1989–93), Iraqi Kurdistan – under Operation Habitat (1991), Iraq (1991–99), Western Sahara (1991–94), Cambodia – under UNTAC (1991–93), Somalia – under Operation Solace (1992–95), Yugoslavia (1992), Rwanda (1994–95), Mozambique (1994), Bougainville (1994), (1997–2003), Haiti (1994–95), Guatemala (1997), Yugoslavia (1997–Present), Kosovo (1999–Present), East Timor – under INTERFET, UNTAET, UNMISET, Operation Tower and Operation Astute (1999–2013), Solomon Islands – under RAMSI (2000–13), Ethiopia/Eritrea (2000–Present), Sierra Leone (2000–03), Sudan – under Operation Azure (2005–Present), Darfur – under Operation Hedgerow (2007–Present)?

Recall that after Australian service men and women returned from the Vietnam War, Return Services League prejudice held by many older folk considered Vietnam not a ‘proper war’ like their World War II apparently was.

Journalist Charles Bean, back in the 1940s probably didn’t consider Aborigines or “half-casts” deserving of military recognition in a national war memorial either. Such was Australia’s British Colonisation culture of the era. Although over 1000 Indigenous Australians fought in the First World War, yet before 1980, individuals enlisting in the defence forces were not asked whether or not they were Aboriginal.

The 51 Aborigines who served Australia in the specialist Northern Territory Special Reconnaissance Unit during WWII, didn’t even get paid, nor did they receive military medals for monitoring and defending Australia’s north from Japanese until 1992.

Brendon refuses to accept any evidence that Australia’s First War, The Aboriginal Frontier Wars (1788-1934) ever occurred.

“They were pre-Bean, and my reading of Australian history only extends that far back!”

And who wrote the Australian War Memorial Act 1980? Similar pompous Canberrans?

The (Australian War) Memorial’s official role is to develop a memorial for Australians who have died on, or as a result of, active service, or as a result of any war or warlike operation in which Australians have been on active service.

Brendon ex-MP dear, laws exist such that they be challenged by MPs to reflect contemporary community values.

In response to calls by historians and the community, Dr Brendan Nelson, as head bureaucrat with the Australian War Memorial, he addressed the National Press Club in Canberra. Aside from 90% self-absorption, Brendon confirmed to the gathering that his military history interest starts from Charles Bean’s 1914-1918 War correspondence. Brendon chooses to limit his responsibility for managing the Australian War Memorial thence forward.

In his address, Brendon ignored the Australian Frontier War (1788-1934). He only spoke of it when asked questions by journalist Michael Brissenden of the ABC. Brendon was asked:

“Dr Nelson, just a reflection, I think probably everything’s politics and the AWM is probably politics enough too. Its mandate is to help remember Australians remember, interpret and understand the nation’s war experiences. In that respect, why is it that the War Memorial continues to refuse to acknowledge the fierce battles between Australians and Australian Aborigines and pastoral settlers – the Frontier Wars? Is there any suggestion that that will change? It’s estimated 20,000 – the conservative estimates are 20,000 Aborigines died in those wars, massacres right up until the latest in the 1920s. Surely that’s a very significant part of Australia’s military history and if that is not the War Memorial’s mandate, then why not change it?”

Brendon replied, relying on his Charles Bean Old Interpretation :

“Well, Michael, look, it’s a very good question and I’m glad you asked me it. I referred in part to Charles Bean and, of course, the origins of the War Memorial itself, and Australia, as we all know, was federated in 1901, and prior to that we had sent troops from the colonies overseas to Sudan and to do some other things overseas.

But the Australian War Memorial is the story of Australians in war deployed on behalf of Australia overseas, not a war as it is described within Australia, in this case against colonial militia, in some cases British forces and Indigenous Australians. And you’re absolutely right, I think our nation needs to reflect on the fact that the story is not told.

But I put to you the Australian War Memorial – and amongst those 102,700 names are several thousand Indigenous Australians who to their immense credit when you think of the First Fleet in 1788, you think of the diseases and all of the things Paul Keating described in his Redfern speech so eloquently, and you think of the consequences of our European ancestors arriving here, building the nation as they did from remarkably difficult origins, the cost borne by Indigenous Australians, in particular, is a story that has to be told.

But the Australian War Memorial is not in my very strong view the institution to tell that story. The Australian War Memorial, as I say, is about Australians going overseas in peace operations and in war in our name as Australians. The institution that is best to tell those stories, in my view, is the National Museum of Australia and perhaps some of the state-based institutions who are most likely to have whatever artefacts or relics that exist from this period in our history.

I think those who argue for the story to be told are absolutely right, absolutely right. But I strongly believe the Australian War Memorial is not the institution that’s doing it. So, look, I’ve got, what, four years and two and a half months to go. So in four years and two and a half months, whoever’s next, bowl the question up.”

Brendon was never a leader. He’s part of the Burley Griffin swamp.

So Brendon relegates the 22,000 who died on Australian soil fighting a colonial conflict to the National Museum of Australia along with artefacts to be put on display next to archaeological relics. He pompously relies on Keating’s attribution of disease to dismiss the 22,000 killed. He degrades their worth, their human significance and dismisses their value to current generations of Australians. He arbitrarily splits the truth of Australia’s military history between the War Memorial and a Museum.