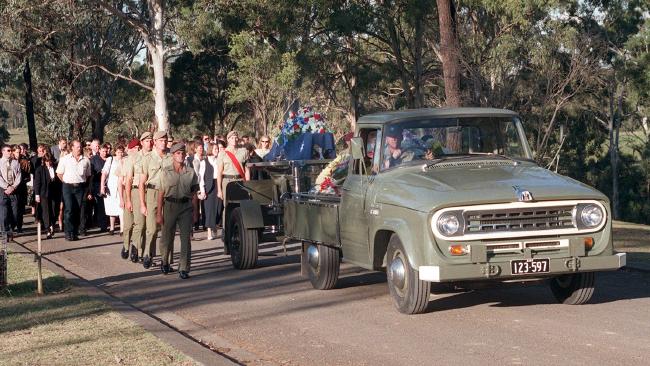

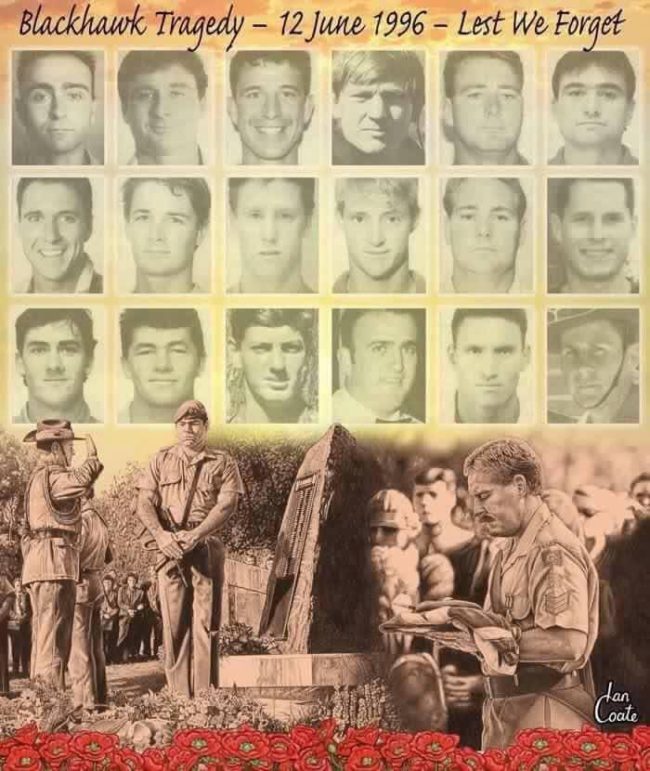

Eighteen Australian elite soldiers and flight crew perished on this day in 1996; this now the 21st anniversary. We honour their service. Rest in Peace.

The survivors, families, friends, colleagues and emergency responders shall never forget, and Australians must not. We owe them all a gratitude for serving our country and their sacrifice.

The Army and the media refer to what happened as ‘The 1996 Black Hawk Tragedy‘. It was a disaster waiting to happen.

It was during a joint night-time SAS counter-terrorism training exercise west of Townsville, four years in advance of deployment for the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

On the evening of June 12, 1996, at 6.30pm, two Sikorsky S-70-A9 Australian Army Black Hawk helicopters flying in a formation of six collided during a night training exercise in the High Range training area, 44km southwest of Townsville. The whole exercise was conducted in darkness – requiring the pilots to use night vision goggles (NVG – ‘no visuals guys’).

The Black Hawks were travelling at 100 knots, just 100 feet above ground, or just above the tree tops. The six aircraft were approaching the target area when the crash happened. At what should have been 30 seconds from the landing zone, one of the helicopters veered to the right, clipping the tail rotor of another helicopter.

The first Black Hawk crashed immediately, killing 12 people on board. The second Black Hawk was able to make a crash landing, but unfortunately caught fire and another six Army personnel were killed. Twelve others were injured. Fifteen soldiers of the Perth-based 1 Sqn SASR and three aviators of the Townsville-based B Sqn 5 Avn Regt lost their lives in the accident.

Townsville shall never forget. It was Australia’s worst peacetime military disaster after the collision between HMAS Melbourne and HMAS Voyager in 1964 which killed 82 servicemen.

The Blackhawk disaster, left 11 children, ranging in age from two to 15, without fathers.

Under the Army’s plan, four groups of SAS troops would rappel on ropes from the hovering Black Hawks and attack the “terrorists”, using live ammunition. They would be backed by SAS snipers in two other helicopters, with mortar support. The target area was Fire Support Base Barbara, a gun emplacement.

No aerial maps were produced at the briefing. No reconnaissance had been done by the pilots. The only map was one drawn by the SAS, mainly to guide troops on the ground. It was put up on a whiteboard, and it was wrong – it depicted a nonexistent gun emplacement northwest of the point where Black One, flown by a relatively inexperienced pilot, was to drop its troops.

Despite the lack of accurate maps, the daylight oper¬ation went ahead smoothly and Black One, the lead aircraft, offloaded its troops without incident. the pilot of Black Two, a senior member of the flight squadron, suggested to the pilot of Black One that he had dropped his troops at the wrong point. But they agreed to go to the same points in the night mission.

About 6.30pm, the six Black Hawks took off. There was no moon, little wind and the remains of the sunset glowed on the horizon, which interfered with the night-vision ¬goggles worn by the aircrews. About 11km from the target, a “three-minute” call was given. The helicopters began “contour flight”, dipping and rising over the ridges and valleys at about 100 knots to disguise their approach.

The plan was that the three leading Black Hawks would come in abreast in order to drop their troops in a line. But a few hundred metres from the target, the formation was off track. Black One made a series of right-hand moves towards Black Two, which was in the middle of the formation, and hemmed in by Black Three.

Burke was attempting to climb when Black One’s rotors smashed into the tail of his helicopter.

Black One was doomed. Fuel from Black Two was sucked out over its engines, resulting in a mid-air explosion and fire. It rolled over and, at a force 50 times that of gravity, according to the Army’s Board of Inquiry report, the aircraft plummeted upside down and exploded on impact. Eleven men died including the pilot of Black One, an incredibly, an SAS trooper and loadmaster aboard survived.

On Black Two, pilot Capt. David Burke had said over the intercom: “I’m sorry, guys, we’re dead.”

“Don’t fucking give up on us now,” his left-hand loadmaster shouted.

Burke didn’t. His helicopter rotated for between five and ten seconds, its tail section in tatters. Burke fought to keep it upright before it crashed.

Burke, his three crew and four SAS soldiers escaped from Black Two.

The extent of Burke’s skill in landing his aircraft remains the stuff of legend. In attempts to replicate the helicopter’s condition in those critical seconds after the crash in a Black Hawk simulator, no other pilot has been able to duplicate Burke’s success in landing his aircraft.

SAS Corporal Dominic Boyle, who later won a coveted Star of Courage, risked his life and ignored his own fractured elbow, the flames of the burning wreckage and exploding live ammunition to save his mates. “There was a lot of bravery that night. I think everyone was a hero,” said Boyle, who described the rescue operation as “organised chaos”. “There was no yelling or screaming, it was fantastic the way the whole thing went … one of the slickest operations I’ve seen. It was all done by torchlight.”

Boyle’s citation states: “He made numerous attempts to save those trapped, to free the bodies of those killed in the wreck of the burning fuselage and to quell the fire with extinguishers.” Then, on the way to hospital, he performed heart resuscitation (CPR) on another injured airman.

SAS Corporal Gary Proctor, also on board Black Two, suffered a broken coccyx and, like Boyle, was awarded a Star of Courage for his rescue efforts in “placing the lives and welfare of his fellow soldiers above his own pain”. “The memories will linger probably forever,” he said.

SAS trooper Gerry Bampton’s spine was shattered. In addition to becoming a paraplegic, Bampton suffered third-degree burns, four other major fractures, head injuries, and nerve and ligament damage. He had to overcome pneumonia, septicemia, urinary tract infections, skin grafts, orthopaedic surgery, manipulative surgery and bladder and bowel operations.

It took $4 million, 50 days of hearings, 6500 pages of evidence, more than 200 exhibits and 100-plus witnesses before the BOI published its final report. It found there had been a “litany of errors” in the command, planning and execution of the exercise. There had not only been poor training, but the pilots were equipped with night vision goggles that left them virtually blind.

It was another Army clusterfuck. Said one, “All our training is for real, most of the guys killed over the years have been killed in training accidents”.

The Board of Inquiry report painted an embarrassing picture of army aviation with helicopters in a woeful state of disrepair, pilots flying as little as 150 hours a year compared to the necessary 300 to be considered competent, and flight instructors leaving the ADF en masse. The 39-strong, $650 million fleet had been effectively grounded for much of 1994 and 1995, with 5th Aviation Regiment having as few as four of the US-manufactured aircraft available to fly.

In the report tried to scapegoat one of the pilots, selectively ignoring the fact that the poilots were required to fly tunnel vision with dodgy inferior night goggles.

In the dark days following the deaths of the 15 SAS soldiers in the 1996 Black Hawk disaster, the SAS Resources Trust was born. In the intervening 20 years, there have been a further nine deaths in service, leaving nine more children fatherless. “This (the Trust) is the phoenix rising out of the ashes,” says SAS Trust chief executive Major Tim Hawson. Modern-day heroes Ben Roberts-Smith and Mark Donaldson, Victoria Cross winners, are both patrons of the Trust, whose mission is to provide additional family support not already covered by Department of Veterans Affairs entitlements. This includes education, family relocation, home security and medical and dental services required due to financial, emotional or psychological hardship.

What a national disgrace that soldiers have to fund their own trust to care for their fallen!

And despicable subsequent comments by Liberal Senator Ian Campbell on behalf of Australia’s Minister for Defence in Australia’s Parliament on 6 March 1997:

“Equipment worth $37 million was destroyed (give a shit)…the Defence Department acted swiftly to ensure that the injured survivors and the families of those who lost their lives were paid such compensation and provided with as much ancillary support as existing legislation allowed. This was done as quickly as was possible (crap).. The accident was not caused by unserviceable night vision goggles.. In addition, the Chief of Army has decided to take administrative action against two other personnel.”

Senator Campbell chose not to mention the Army’s poor and rushed planning (of the mission); the failure to gather accurate data about the target area; the changing the mission between the day rehearsal and the night run; choosing a target that was too hard to locate under NVG’s; and appointing an inexperienced flight lead for such a difficult mission.

Under Australia’s Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Bill 2003, a serviceman or woman killed in peacetime service, is only worth up to $103,000.

Last words:

Capt. David Burke, 5 Avn: “The NVG’s have a limited field of view, only about 40 degrees. It’s very difficult to see a lot of things. It’s like trying to fly watching a small TV screen. It’s obviously a very difficult task. Flying the sorts of missions that we were doing, that we do, is the most demanding thing we do.”

AN/AVS-6 Aviator’s Night Vision Imaging System (ANVIS) manufactured by Intevac based in Connecticut.

AN/AVS-6 Aviator’s Night Vision Imaging System (ANVIS) manufactured by Intevac based in Connecticut.

Capt. Simon Edwards, Co-Pilot, BH2: “All you’ve got — your whole world consists of two little green spots in front of your eyes. There’s no peripheral vision and you don’t realise just how much peripheral vision you use in day-do-day life, and particularly flying, until it’s removed. It’s just black, completely black, particularly on a very dark night.”

W.O. Bill Mark, 5 Avn: “I always used to say that, you know, with night vision goggles, your eyes bleed at the end of it because you’re looking through that tube for so much, and so hard, because, and your concentration — yeah, you’re very, you know, you get a high level of concentration loss in doing that.”

Last October 2016, Defence Minister Marine Payne announced the Army was buying different night goggles and related gear costing $232 million, this time from US manufacturer L-3 Technologies. Apparently the AN/PVS-31 Aviator’s Night Vision Imaging System is better that the previous lot. Really?

AN/PVS-31 Aviator’s Night Vision Imaging System (ANVIS) manufactured by L-3 Technologies based in Londonderry, New Hampshire.

AN/PVS-31 Aviator’s Night Vision Imaging System (ANVIS) manufactured by L-3 Technologies based in Londonderry, New Hampshire.

Bloody Army guinea pigs.

We remember them.

- LCPL David Andrew Johnstone

- TPR Jonathon Gaius Sanford Church

- TPR Timothy John McDonald

- SAS CAPT Timothy James Stevens

- CPL Brett Stephen Tombs

- TPR David Frost

- CPL Michael Colin Baker

- TPR Glen Donald Hagan

- CPT John Berrigan

- TPR Gordon Andrew Callow

- TPR Michael John Bird

- CPL Mihran Avedissian

- CPL Andrew Constantindis

- CPL Darren John Smith

- SIG Hendrick Peeters

- LCPL Darren Robert Oldham

- SGT Hugh William Ellis

- CAPT Kelvin James Hales