This article is an extract of an academic paper first published by the Australia First Party on Australia Day 2016. It is in 12 parts. The entire paper may be obtained as a PDF in the public domain from the internal link at the end of this extract. Authors: Jim Saleam and Lorraine Sharp, Sydney, January 26 2016.

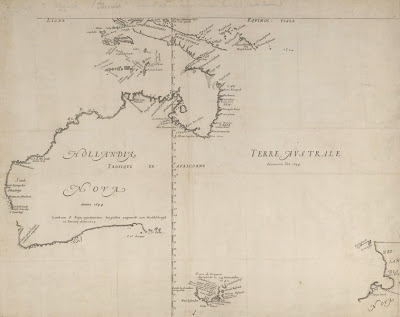

The Southern Continent was a mystery to the first modern white men who saw it in 1521. Ultimately, the Portuguese, the Spaniards, the Dutch and the British sailed around it and mapped it.

Terra Australia Incognita 1644

Terra Australia Incognita 1644

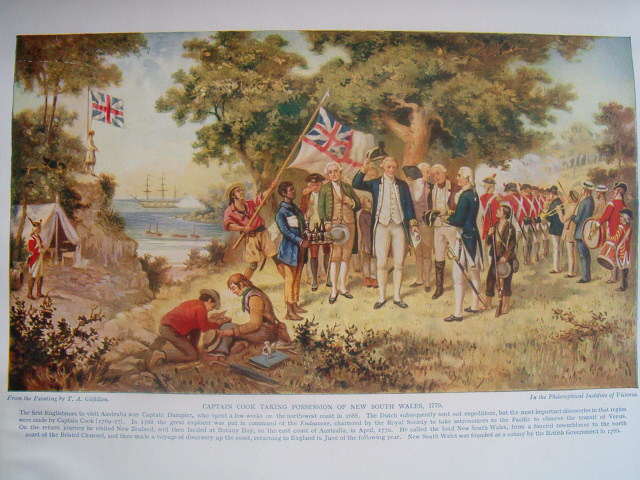

We may debate who amongst this group first stepped ashore, or left a mark upon its soil – and perhaps even who first mapped its eastern coasts. But it was the British who claimed its eastern realms in 1770 and claimed British sovereignty over this domain he called ‘New South Wales’.

Lieutenant James Cook raises the Union Flag on Possession Island, 22 August 1770

Lieutenant James Cook raises the Union Flag on Possession Island, 22 August 1770

Finally they asserted sovereignty over all of it, settling it at first with the cast-offs of the industrial revolution and the slums populated by the successor generations of the Highland Clearances of Scotland (all labelled ‘convicts’) and their gaolers and a few soldiers with their families. It was not an auspicious beginning. Grim towns hugged its coasts and sparse settlements put down spindly roots in parts of the interior.

Originally, the Continent itself was seen as just an immense nothing, barren to the west and in other some areas, wild and natural and populated by dark-skinned natives with nought to trade. It was called New Holland or the Great Unknown Southern Land. It was only in the nineteenth century that it drew its name ‘Australia’. The quarrels of the European mercantile states in the Seven Years War (1756 – 1763) gave the continent geopolitical significance and when Britain settled it first in 1788, this very happening was part of the great on-going contest with France. It was a naval base and a place of resources to weigh against France in the Southern Seas. The colony was a pawn in a war of strategic position. That model boded ugly for Australia a century or so later.

Certainly, those in Britain who ‘counted’ in politics and commerce never imagined their colony of New South Wales as a nation in embryo. Britain had recently lost America and it did not intend to lose its new possession.

The slow development of Australian colonisation was perhaps amazingly and prophetically belied by Arthur Phillip, its first governor, who spoke of it as a new country with a great destiny. Perhaps he stepped beyond his brief? Yet, other colonial governors and leading figures glimpsed that too. Governor Macquarie definitely did when he founded the first industries and planned the development of towns and roads into the interior. Yet the land remained locked up and European settlers were not welcome, so many took the American option, until the discovery of gold in 1851.

Australia’s population grew in size throughout those first several decades down to the Gold Rushes. New colonies were added to New South Wales until six existed.

The idea of a separate Australia lurched slowly into being. The vision of Australia as a great power, a mighty southern land as the poet Wentworth put it, “a new Britannia in another world”, emerged early as a stirring of some dreamers.

John Dunmore Lang grasped at the prospect of “freedom and independence for the united provinces of Australia”, In the 1830’s and 1840’s, he lectured and hectored along that line. It was still a dream.

The Gold Rushes era (1851 – 1870) increased Australia’s population markedly and a more diverse European base came into being beyond the limits of our earlier British (we shall here include the Irish) settlers and convicts. The clashes on the goldfields between the miners and the colonial authorities gave Australia a moment or two in radical democracy and racial nationalism – the Eureka Rebellion of 1854 and the Lambing Flat Uprising of 1861, events as the great Jack Lang would put it a hundred years later, were instrumental in the forging of a free labour system (against both the owners and the Chinese) and the dim articulation of a certain ‘Australianness‘. The Southern Cross Flag raised at Eureka and its variant at Lambing Flat, left a powerful symbolic legacy.

The radical nationalist flag: in the nineteenth century the Flag of the anti Chinese immigration struggle

The radical nationalist flag: in the nineteenth century the Flag of the anti Chinese immigration struggle

Nonetheless, we might say that the Nationalist movement emerged in the cultural springtime of Australia, that period after about 1880 with the birth of The Bulletin magazine, the bushman’s bible, which did so much to define the Australian ‘ethnic’ and cultural identity. We are minded of a great reference:

“By the term Australian we mean not those who have been merely born in Australia. All white men who come to these shores — with a clean record — and who leave behind them the memory of the class distinctions and the religious differences of the old world; all men who place the advancement of their adopted country before the interests of Imperialism, are Australian.

In this regard all men who leave the tyrant-ridden lands of Europe for freedom of speech and right of personal liberty are Australians before they set foot on the ship which brings them hither. Those who fly from an odious military conscription; those who leave their fatherland because they cannot swallow the worm-eaten lie of the divine right of kings to murder peasants, are Australians by instinct — Australian and Republican are synonymous.

No nigger, no Chinaman, no lascar, no kanaka, no purveyor of cheap coloured labour, is an Australian.”

Or as William Lane put it – in Australia “the Teuton, the Latin and the Slav were mingling,” such that a new nationality was “creeping to the edge of being”.

This essential Australianness was the inspiration of our radical-nationalist writers and poets, our labour movement and other patriots. It inspired aspects of the Federation movement that formed the six colonies into one large colony in 1901 – but one with at least the ability and direction to develop into a country.

It was said in the 1890’s that Australia was developing such that it would become a “co-operative Commonwealth”, a “workingman’s paradise”, the property of a new nationality with an ethos of mateship and brotherhood, of the equality of man and woman. That is undeniable and is a point of inspiration today.

In 1891, at Barcaldine in Queensland, the Southern Cross flew again over the shearers’ camps as armed men contemplated revolutionary action in defence of their jobs, their unions and their ethnic identity against the Chinese influx. From Barcaldine came the great (the original) Labour Party.

Hughenden Strike Camp 1891 (north of Barcaldine, QLD)

Hughenden Strike Camp 1891 (north of Barcaldine, QLD)

In 1901 at Federation, the ‘Australianist principles‘, the groundings of national existence, were somewhat acceded to by way of the Historical Settlement.

Opening of the first Parliament of Australia in 1901

Opening of the first Parliament of Australia in 1901

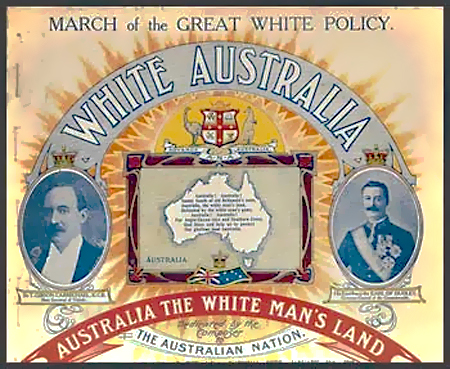

A Constitution proclaimed a certain ‘sovereignty’ over the Continent (albeit on behalf of a foreign state) and the White Australia Policy, the social protection and the industrial protection legislation when summed together with the written document was an organic constitution which set Australia along the path towards nationhood. The organic constitution would survive until 1966 when the White Australia Policy was overturned and each part of the Historical Settlement thereafter was repudiated in turn.

‘March of the Great White Policy’

‘March of the Great White Policy’

Composed by W E Naunton and performed in 1910 in the Royal Exhibition Ground, Melbourne for the Australian Natives’ Association

There are no certainties in the fight for national independence.

“Soldiers marching to Somme” by Anders under license CC NY-ND 2.0

“Soldiers marching to Somme” by Anders under license CC NY-ND 2.0

It is the view of the Nationalists that the Great War, into which Australia was taken in 1914 – represented a great downside in Australia’s gentle path towards national independence. Yes, it gave us the ANZAC legend, but it gave us 60,000 dead. It allowed the conservative sector to usurp the war legend and suggest that a part of Australianness is service at the behest of foreigners. In that sense the Great War was a defeat for our nationality.

The 60,000 dead – the best of Australia. For what?

The 60,000 dead – the best of Australia. For what?

In 1939, Australia went to war again “because Great Britain is at war” and it joined a European war of no interest to the Nation. If Hitler (and then Mussolini) were threats to Australia, it was not demonstrated how this was so. Hence Australians tramped off to the Middle East and Greece, winning new laurels for bravery (of course) but no kudos for the protection of the Nation. The European war was not our war, but the advent of war in the Pacific certainly was of life and death concern to the Nation.

The name of John Curtin is revered by all who put Australia first. We are reminded that it was Curtin who declared war upon Japan in 1941. It was not a matter of we were at war because Britain was at war. It was a matter for Curtin that Australia assert its sovereignty and its identity. That declaration of war was illegal, as Australia had no legal right to declare war. Ironically, Britain had offered the Statute of Westminster to Australia in 1931 which gave Australia that sovereign power, but no government passed it lest Australia be seen as ‘anti British’. Curtin’s government did not get passage in the parliament of the Statute till March 1942. We note here that Curtin declared war on Japan in the name of White Australia, our “laws’ (he said). This was revolutionary conduct and it was the behaviour of a man and a government schooled in the true tradition of labour nationalism. Australia took independence and did not ask for it.

Nationalists would perceive of Curtin’s government as a model for the future. It was a government prepared to mobilize the entire Nation, to wage national revolutionary war on our territory if necessary, without cease and regardless of the human and the material cost, until victory.

The Curtin period was a grand moment in nation-building in Australia. Only Curtin could speak of war and bloodshed but mix it with the Australo-spiritual poetry of Bernard O’Dowd, a nationalist hero of the then yesteryear; only Curtin could have been fighting a total war, but plan the re-birth of the ideals of a co-operative Commonwealth.

However, as is the long story of the true cause of Australian independence, the Curtin cause of nationalist labourism, existed in a world of imperialism and powers and ideologies grabbing at the nation’s resources and at its soul. In the moment of victory, there was defeat.

Henry Lawson wrote that in Australia’s darkest yet grandest day, we would need men like Peter Lalor, the leader at Eureka. John Manifold said that we would need a thousand like Ned Kelly to raise the Flag of Stars. All true. Whomsoever our leaders are who get us to the moment that the Australian People command their state, we would require another Curtin to guide us to victory.

John Curtin: radical leader and nationalist, Hero of the Nation.

John Curtin: radical leader and nationalist, Hero of the Nation.

Read Entire Paper:

https://australiafirstparty.net/australian-identity/presidents-messages/2016-2/feb-7-true-cause-of-australian-independence/