Loading...

Loading...

“I love the spring. It means the wattle comes out again. It is a symbol of everything one loves about Australia and the ideal of the uniqueness of Australia. ” — Manning Clark.

Loading...

Loading...

The Golden Wattle is Australia’s celebrated National floral emblem

The Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) is a beautiful plant which grows in south-eastern Australia, notably around the ACT, in southern NSW, in the Adelaide Hills and widely in Victoria. There is a large stand situated about twelve kilometres distant from Parliament house, on Mt Jerrabombera just outside the ACT.

Golden Wattles are variable in size and take the form of large shrubs or small trees depending on their location. There is also some variation in leaf width across the natural range of the species. In the Adelaide Hills, for example, the leaf is much wider than on the ACT variety [although note that mature wattles do not have true leaves; they are flattened leaf stalks]. Large flower size, on the other hand, is a characteristic of all Golden Wattles. The flowering season is late winter to early spring and so can be suitably associated with 1 September. Like many other members of the family, Golden Wattle has delicately scented blossom. Lifespan for the species is not long, only about ten years.

Wattle-like plants found overseas are often spiny, they tend to have less spectacular flowers and are known as mimosas. In Australia the Acacias are our largest plant genus with about 750 species. The Australian name wattle is an early colonial term which relates to the use of the springy stems as wattles (i.e., interlaced rods) in wattle-and-daub huts.

Aboriginal people have a strong traditional relationship with a number of wattle species, which have been used by them for food, fuel, medicine and various woodcrafts.

Golden Wattle is a relatively hardy species and has been planted in all States. Frost-resistant varieties can be chosen for the inland. For example, Canberra’s Golden Wattles are unaffected by heavy frosts. Some care may be needed in order to prevent invasion of local bushland in, say, Western Australia where the species is not endemic, which is why the practice of distributing A. pycnantha seed on Wattle Day may not always be welcome. Such invasion by another popular species, Cootamundra Wattle (A. baileyana), has occurred in the ACT.

The first official move towards recognising the wattle as a national symbol took place on 19 April 1984, when the Governor-General proclaimed Australia’s national colours to be green and gold. This was an important step, because blue and gold had also traditionally vied for this status and there had been some confusion and personal preference involved. Blue can still be accepted as an unofficial national colour because blue represents a clear Australian sky as the background to flowering wattle.

On 1 September 1988, the Golden Wattle was declared officially as Australia’s national floral emblem. While Golden Wattle had long enjoyed that status informally – note its prominent place within the Commonwealth Coat of Arms dating from 1912 (frontispiece) and on the insignia of the Order of Australia – it had taken strong supporters of the emblem, notably Maria Hitchcock and also the Society for Growing Australian Plants (SGAP), to persuade the Federal Government to grant official recognition in the Bicentennial Year.

Another aim of Maria Hitchcock and her fellow enthusiasts was to revive Wattle Day, which traditionally had been celebrated on the first day of Spring in several States although 1 August was the accepted date in NSW. At her urging, and with growing support from others, the Commonwealth and the States agreed in 1992 that Wattle Day would henceforth be the same in all States and Territories, that is, the first day of September. This was a necessary step towards reviving Wattle Day as a national celebration.

A Brief History of Wattle Day

Although wattle was associated with Australia from very early days, its significance increased around the time of Federation. The first celebration of Wattle Day was held on 1 September 1910 in Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Plans in 1913 to proclaim the wattle a national emblem and celebrate Wattle Day nationally were interrupted by World War I, but wattle remained a strong symbol of patriotism during the war years. Sprigs of wattle and colourful badges were sold on Wattle Day to raise money for the Red Cross. NSW changed the date to 1 August in 1916 because that allowed the Red Cross to use the earlier flowering and more familiar Cootamundra Wattle rather than Golden Wattle. Wattle was sent overseas in letters during the war and was presented to homecoming service men and women at what must have been an emotional moment.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Wattle Day continued to be celebrated, still associated with raising money for charity but also featuring special activities for children and ceremonies to mark the occasion. Maria Hitchcock states in her book (Wattle, AGPS 1991, held in the Parliamentary Library) that Wattle Day was an annual event in NSW, Queensland, Victoria, SA and Tasmania but does not seem to have been recognised in Western Australia or the Northern Territory. Wattle Day was apparently a strong event in NSW schools. Unfortunately, the tradition was virtually lost after World War II. It was only in the 1980s, in prospect of the Bicentennial and in sympathy with rising national concern for Australian flora and the environment generally did a suggestion to revive Wattle Day receive attention.

It has been fortuitous that, just when the revival of Wattle Day seemed to be losing its way, the ACT Division of the Red Cross decided to take it on for fundraising purposes. The initial ACT Red Cross Wattle Day campaign launch was in 1994. Another welcome decision has come from the State and Territory cancer societies and councils to hold Daffodil Day on a Friday in late August, not on Wattle Day as previously.

Wattle Day Significance to Australians

What do wattles mean to Australians?

It’s Australia’s emblem

- Australia’s national flower is the golden wattle

- Australia’s national colours were inspired by the golden wattle

- The coat of arms of Australia features a spray of wattle in the background

- Wattle Day on the first day of Spring (Sept 1) has been a national day of celebration in Australia since the early 1900’s.

It’s part of our shared cultural history

- Wattle has been utilised by Aboriginal and Islander peoples for thousands of years.

- Wattle was an important pioneer species. Colonists used wattle branches in the construction of wattle and daub houses.

A symbol of our land

- Wattle is the largest genus of vascular plants in Australia, it is found in every state.

- Acacia (wattle) is a genus of Gondwanian origin, it has been in this land for 35 million years.

A symbol of Australia’s best

- The Order of Australia medals, the highest honour an Australian civilian can receive, is designed around a golden wattle blossom.

- Many Australian Defence Force medals, such as the Long Service Medal include wattle in their design.

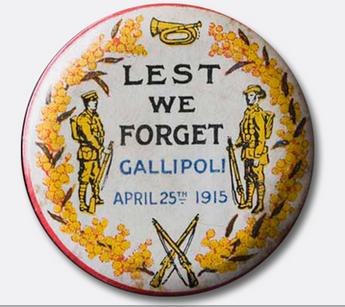

Part of the ANZAC legacy

- During the First World War sprigs of wattle were often sent with letters to soldiers on service abroad, as a reminder of the things they loved at home.

- Traditionally, wattle was placed with fallen Australian soldiers before burial.

- Wattle appears on many Australian Defence Force medals, colours, standards, guidons and banners.

- Wattle sprigs were sold to raise money during the First World War.

- Australia’s first ANZAC memorial was erected in Wattle Grove in Adelaide on Wattle Day in 1915.

- During the evacuation of Gallipoli, Chaplain Walter Dexter scattered wattle seeds as he left, he wrote: “If we have to leave here I intend that a bit of Australia shall be here.”

Part of our sporting traditions

- All of Australia’s national sporting teams wear wattle inspired green and gold uniforms.

“Under the Southern Cross I Stand

A sprig of wattle in my hand,” — Traditional Australian cricket chant

A symbol of remembrance and new beginnings

- Australians have used wattle as a symbol of national solidarity in times of crisis.

- Wattle is often worn at Australian citizenship ceremonies to symbolise new beginnings.

“Wattle is a symbol as broad and inclusive as its reach into history is long. Wattle grows in all parts of Australia, differing varieties flowering throughout the year. It links all our people, from our first to our newest at citizenship ceremonies. It touches all levels of society, from very early pioneers and World War I diggers, buried with a customary sprig of wattle, to victims of the Bali bombings and to our nation’s best whom we honour with Order of Australia awards, the insignia of which is designed around the wattle flower. Wattle Day on the first day of Spring (Sept 1) is a national day of celebration in Australia. When the blaze of wattle lights up our landscape each year, let’s remember that the wattle is a symbol of our land that unites us all.” – Extract from Wattle Day by Terry Fewtrell, President, Wattle Day Association. ABC Radio National.

Some Australians can be uneasy with sentimental displays of national feeling so it is reasonable to ask why the traditional Wattle Day should be revived. After all, if this is a genuine folk day, why did it lapse when ANZAC Day has not?

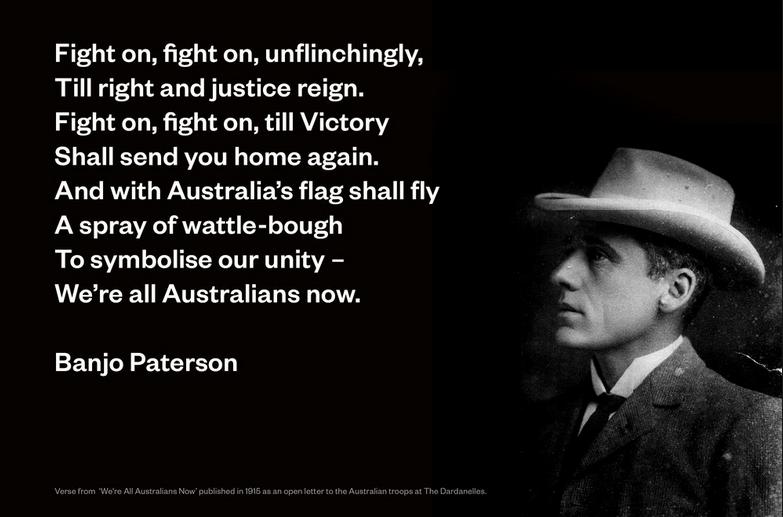

The Golden Wattle is entwined with the ANZAC legend

The Golden Wattle is entwined with the ANZAC legend

When Australian troops left for foreign shores, the wattle travelled in pockets, in kitbags, a reminder of home and the country they had left, and a keepsake to sustain them till they came home. It also became customary for mothers and sweethearts to enclose sprigs of wattle with letters to soldiers on service abroad. The sprigs were welcomed by soldiers at the front. A. H. Scott of the 4th Battery, Australian Field Artillery, recorded his feelings about the custom in his poem A Little Sprig of Wattle (1916). The first verse reads:

My mother’s letter came to-day

And now my thoughts are far away,

For in between its pages lay

A little sprig of wattle.

The best arguments for Wattle Day need to take into account the present economic and cultural insecurity experienced by a significant number of Australians which needs to be balanced by a celebration of hope and common purpose.

“It can be that in moments of intense self-doubt, seeing glorious wattle blossom can reaffirm our faith in ourselves; remind us of that eternal optimism, that nature rejuvenates itself and continues the cycle of life – and so can we.” — John Olsen

The economic insecurity largely comes from Australia opening itself up to competition with the world in recent years and was less prevalent in the comfortable 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. The need for increased competitiveness is more-or-less a consensus position of Australian politics, but many people have been adversely affected, at least in the short-term.

Another, often unspoken problem is a combination of cultural confusion and erosion. Our children (and the rest of us) have always tried to ignore the chronic cultural disorientation of being ‘Down Under’, especially in regard to the important national holidays. To illustrate the point, our Easter is full of symbols of early Spring (egg, young rabbits, chicks, etc.) but the symbolism and the season have no correspondence in the Southern Hemisphere.

Australia’s Christmas is very mixed up, with a warmly wrapped ‘Santa’ and his sleigh now commonly teamed with waratah and holly leaf decorations on supermarket windows! Australia Day itself is seen by some as a NSW-dominated celebration, as largely an opportunity for a multicultural display, or as a marking of the invasion of the continent by Europeans. The Queen’s Birthday Holiday has become controversial. The first day of January marks the start of Federation but is also New Year’s Day. There is no national Labor Day. Children know something about an overseas May Day, the may queen and the may pole of the European high Spring but there is no equivalent national Spring festival here. The only national folk day of universal acceptance is ANZAC Day.

An example of cultural erosion affecting young and old is the increasing foreign sell-off of traditional Australian company icons.

If we add to the above the invasion of American culture, now accelerating through television and computer networks, together with national confusion over whether we are or should be Asian or Asianised; a celebration of ‘Australianness’ symbolised by wattle, the popular national floral emblem (which is not for sale) combined with a celebration of the coming of Spring should be a very special occasion every year. An added attraction is that Wattle Day dates back more than eighty years and is a part of Australia’s history.

Wattle and Wattle Day can symbolise virtually anything we want, but they relate generally to Spring, being Australian, the Australian environment, and history. Spring has many positive values such as optimism, bounty and abundance, reliability, colour, new life and so on. We can celebrate our ‘Australianness’ on Wattle Day in quite a different way from Anzac Day, which in recalling past wars glorifies Australian qualities of courage and mateship. Wattle Day, by contrast, looks forward (to Spring) and can celebrate the nation’s undoubted qualities of good humour, fairness, generosity, informality and democracy.

Want to know more about why we celebrate National Wattle Day?

http://www.goldenwattleflag.com/why-the-wattle/

Celebrating Wattle Day on 1st September

- WEAR a sprig of wattle or Australia’s colours of green and gold

- GREET each other with ‘Happy Wattle Day’

- Go for a walk to enjoy wattles in flower around your suburb or nearby bush

- ORGANISE a picnic, lunch, morning/afternoon tea, BBQ or dinner for your family & friends

Since 1992, National Wattle Day has been on the 1st September in all of Australia’s States and Territories. Before then, Australians in different States celebrated wattle day on different days between August and September.

Wattles have long had special meanings for Australians and in 1988 the Golden Wattle (Acacia pycnantha) was officially gazetted as Australia’s national floral emblem.

Visit the Official Wattle Day Website of the Wattle Day Association Inc: http://www.wattleday.asn.au/

Wattle Day should be a simple, sentimental and uncomplicated occasion – the last thing wanted is long, boring ceremonies. In the ACT the Day will certainly be marked by Red Cross badges, book marks and perhaps other merchandise for fundraising promotion by that organisation. This is certain to raise the local profile of the day for adults, and for many this would make it equivalent in status to Poppy Day, Daffodil Day or Red Nose Day. Wattle Day can rise above these in significance, however. For example, Wattle Day could become a favoured occasion for conferral of citizenship. Another possible emphasis is on selling wattles and other Australian plants for home and public gardens; this is already in train at the Australian National Botanic Gardens, which has a Wattle Week associated with Wattle Day. Wattle Day could thus be associated with water conservation and better Australian garden design, plant selection, etc., to develop what is still quite primitive use of native plants for this purpose.

The traditions and sentiments surrounding Wattle Day can translate very well to young children and primary schools. Up to now, education authorities’ approach to the revived Wattle Day has been generally disappointing, the Day being left to busy school principals to decide whether to celebrate or not. So as not to intrude on already packed school calendars, it is important that Wattle Day festivities in the schools last only one day, and not have a heavy curriculum input over, say, a week. Some suggested activities for primary schools on Wattle Day are:

- decorating classrooms

- plays/poetry readings/songs

- the teaching of Wattle Day history

- folk dancing

- planting Golden Wattle or other native species on school grounds

- just having a party

- art, posters, etc.

Perhaps each year could feature a new theme such as history, environment, flower arranging and so on. If all this seems a little too much for some boys, perhaps they could be reminded that their sporting heroes carry the colours of wattle!

Traditionally, Wattle Day was strongly associated with planting Australian trees and shrubs. This activity has been largely taken over by conservation initiatives such as Landcare, Greening Australia, Arbour Week and so on. In that case, perhaps Wattle Day could concentrate on the planting of Golden Wattle itself; the species is short-lived and needs to be replaced fairly often. Also, many Australians young and old would not be able to recognise the national floral emblem because it is not as commonly planted as it could be. In the tropics, Golden Wattles could be replaced by more suitable Acacia species.

A leadership role for the Australian Government

“The Golden Wattle has become our cherished symbol of celebration, of joy, of sadness and of remembrance. And of home wherever we may be. And of national unity. Rightly, quite apart from its own intrinsic significance as our national floral emblem, it inspires our national colours, decorates our national Honours and is incorporated in our national Coat of Arms.” — Sir William Deane

Meaningful support for Wattle Day at Federal level need not be costly, and should mainly involve promoting and distributing literature, and seeing to coordination of related activities.

Wattle, the book written by Maria Hitchcock, has been well produced and needs a much wider circulation. It has often been suggested that the Commonwealth could donate a copy to each primary school library nationwide.

Available from Dymocks bookstores

Another possible initiative at Australian national level could be to commission a similar book meant to appeal to the very young. This could perhaps be given to each child in a particular year of his/her education. The Commonwealth could also distribute carefully prepared Wattle Day kits to schools, in cooperation with State education bodies.

Wattle Day seems to lend itself particularly well to poetry.

‘Australia’s Emblem’ by Margaret Shaw

‘The Wattle Celebrates‘ by An Australian

‘The Wattle’ by Henry Lawson

‘Wattle Day’ by Francis Duggan

‘Cootamundra Wattle’ by Francis Duggan

‘Wattle Trees’ by Denis Kevans

The Federal Government could hold a regular poetry competition nationwide with an attractive prize.

Citizenship ceremonies were mentioned earlier as being most suitable for Wattle Day. The Government could encourage such timing so that it becomes a tradition.

Lastly, Wattle Day can be made more closely associated with the Order of Australia. For example, past newspaper publicity for entries on ‘What it is to be an Australian’, in the name of the Order of Australia Association, could have been more closely linked with Wattle Day. One can even conceive of new awards of the Order being made on – Wattle Day.

Happy Wattle Day!