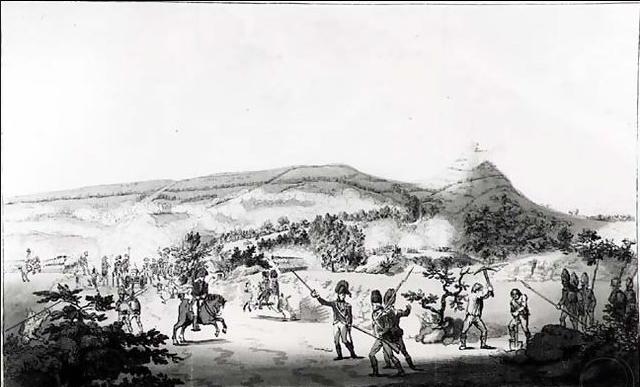

The Castle Hill Political Uprising took place on Monday, March 5, 1804 at now Rouse Hill in north-western Sydney. It was the first rebellion in Australian history. Involving Irish convicts (for the most part, political offenders), the uprising began with the rebels’ seizure of the New South Wales convict station at Parramatta on March 4 and culminated in a clash between the rebels and government troops on the following day. The actual scene of this clash was Vinegar Hill (now called Rouse Hill), about 10 miles (16 kilometres) from Castle Hill.

It was named after the Battle of Vinegar Hill of 1798 in Ireland which had involved the United Irishmen’s uprising against the British overlords on a similar looking hill. In fact some of the rebels at Sydney’s Vinegar Hill battle were indeed veterans of the Irish Vinegar Hill battle of six years prior. Many convicts in the Rouse Hill area had been involved in the Irish 1798 rebellions and had been arrested and sentenced as exiles-without-trial to the New South Wales penal colony, transported from late 1799. So they were effectively political prisoners of the British. Most of them arrived on the Transports ‘Friendship‘ and ‘Anne‘ without any record of trial or sentence.

Australia’s Battle of Vinegar Hill (also referred to as Castle Hill) was a rebellion by convicts against a cruel British tyranny in the colony of New South Wales. It was the first and only major convict uprising in Australian history. “..the first dust we have had of this kind since the colony has been formed.”

On 4 March 1804, 233 convicts led by Phillip Cunningham (a veteran of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, as well as mutiny on the convict transport ship ‘Anne’) escaped from a farm intent on capturing ships to sail to Ireland. Cunningham and William Johnston, another Irish convict at Rouse Hill, planned the uprising in which over 685 convicts planned to meet with nearly 1,100 convicts from the Hawkesbury River area, rally at Constitution Hill (now Toongabbie), then march on Parramatta and then on the New South Wales colonial government at Sydney Cove itself to commandeer a ship home to Ireland.

On the evening of 4 March 1804, a hut at Rouse Hill was set afire as the signal for the rebellion to begin which was not seen by the convicts at Green Hills (today’s Windsor) on the Hawkesbury River. With Cunningham leading, the rebels broke into the Government Farm’s buildings, taking firearms, ammunition, and other weapons. The constables were overpowered and the rebels then went from farm to farm on their way to Constitution Hill at Parramatta, seizing more weapons and supplies including rum and spirits.

But the rebels at Constitution Hill had difficulty co-ordinating their force as several parties had lost their way in the night. They commenced drilling, while a party tried to enter Parramatta. Around 30 were shot and killed at the western gate of the Governor’s Domain by government forces, but withdrew on learning the arsenal, Commissariat and other buildings were defended. The messenger, a government agent, sent to pass out the rising instructions had ‘defected’ to the authorities and those in the town and environs did not receive the call-out, nor did the convicts at the Hawkesbury.

News of the uprising spread quickly to Sydney and Governor King dispatched soldiers of the New South Wales Regiment to Rouse Hill. The New South Wales Regiment was more infamously known as the self-serving and corrupt “Rum Corps”. There was great panic amongst the colony of just around 5,000 inhabitants at the time with particularly hated officials such as chief Anglican clergyman Samuel Marsden (the infamous flogging parson) fleeing the area by boat down the Parramatta River.

Cunningham was sent to parley (negotiate) with the British commander of the soldiers under a flag of truce. Cunningham: “If they had any real grievance, he would endeavour to get it redressed. Cunningham advanced, and took off his hat, and with it in one hand and a sword in the other replied ‘Death or Liberty’ “.

, but the soldiers disregarded the flag and fired on the rebels. The result was more of a massacre than a battle.

In the actual battle, NSW Regiment Quartermaster Sergeant Thomas Laycock, on being given the order to engage, directed over fifteen minutes of musket fire, then charged cutting Cunningham down with his cutlass. The now leaderless rebels first tried to fire back, but then broke and dispersed. At least fifteen rebels were killed at Rouse Hill.

Several convicts were captured and up to 150 were killed in the pursuit which went up to Windsor all day until late in the night, with new arrivals of soldiers from Sydney joining in the search for rebels. Large parties who lost their way in the night turned themselves in under the Amnesty or made their way back to Rouse Hill.

Martial law was quickly declared and the rebels were hunted down by the colonial forces and captures. Three hundred were eventually brought in over next few days. Cunningham was arrested. Nine of the rebel leaders were executed and hundreds were punished with 200 or 500 lashes then allotted to the Coal River chain gang. Twenty six rebels were sent to the Newcastle coal mines, others put on good behaviour orders against a trip to Norfolk Island, and most pardoned as having been coerced into the rising.

Cunningham was court martialled under the Martial Law and hanged at the Commissariat Store at Windsor. His grave is located at Windsor.

The battle site is believed to be at the site of Rouse Hill Estate, and it is likely that Richard Rouse, a staunch establishment figure, was subsequently given his grant at this site specifically to prevent it becoming a significant site for Irish convicts. Vinegar Hill Post Office opened in 1857 and was renamed Rouse Hill in 1858 after Richard Rouse (1774-1852), a prominent free settler who arrived in the colony in 1801. His first grant here was in 1802 and his second grant was in 1816.

“Unfortunately the wells of truth are often, perhaps generally, poisoned by the victors.”

~ Kevin Moore, in ‘Behind Vinegar Hill’, 1982.