July 19, 1916 saw the worst single loss of life in Australian military history. Australia’s ‘Cobbers’ sculpture on the other side of the world, poignantly dominates Australian Memorial Park surrounded by farmland along Rue Delval outside the French town of Fromelles. It commemorates the thousands of Australian men who fought and died in Australia’s first attack to defend France in The Great War 1914-1918.

‘Cobbers’ symbolically honours Sergeant Simon Fraser’s (a farmer from Byaduk, Victoria) selfless sacrifice under risk of sniper fire to rescue his wounded cobbers from No Man’s Land after the horrific night’s carnage. In his letter home from the Front, Simon wrote:

“We found a fine haul of wounded and brought them in; but it was not where I heard this fellow calling, so I had another shot for it, and came across a splendid specimen of humanity trying to wriggle into a trench with a big wound in his thigh. He was about 14 stone weight, and I could not lift him on my back; but I managed to get him into an old trench, and told him to lie quiet while I got a stretcher. Then another man about 30 yards out sang out “Don’t forget me, cobber.” I went in and got four volunteers with stretchers, and we got both men in safely.”

Australian Memorial Park has been respecfully positioned by a grateful French at the point where the German lines crossed Rue Delval and there remain several surviving battlefield fortifications. The memorial park is just about 100m from V.C. Corner Australian Cemetery and Memorial at the point where the Allied lines crossed the road.

V.C. Corner Cemetery

VC Corner is so-named because of the fighting that took place there in 1914 shortly after the outbreak of war. A number of British VCs were awarded for action in the vicinity, but none are interred in the cemetery. It is the only ‘all-Australian’ cemetery in France. It contains the remains of 1181 Australians of the 5th Division killed in the calamitous attack on 19/20 July 1916. There are no headstones in the VC Corner cemetery. The bodies of the fallen are laid separately in two large unmarked graves topped by a rose garden. The names of the men believed to be in the cemetery are engraved on the rear wall.

The bodies were not separately identifiable at the time of their recovery immediately after the Armistice in 1918. They had lain on the field for 2 1/2 years. Their ID tags had largely been removed by comrades in the immediate aftermath of the battle, in an effort to recover the wounded and to ensure that the fate of the fallen was confirmed to families. This was done at great personal risk and many additional casualties were sustained in the process.

The bodies of the dead who were identified are buried in a number of nearby cemeteries including Rue Petillon and Rue de Bois, towards Fleurbaix, and more recently, Pheasant Wood adjacent to Fromelles. The latter was dedicated in 2010 and contains the bodies of soldiers discovered in a Mass Grave in 2008 thanks to the dedicated efforts of Melbourne school teacher Lambis Eglisios who had extensively researched the area in an effort to account for hundreds of ‘missing’ soldiers. The men in the Mass Grave had largely been killed behind German lines and were primarily from the 8th Brigade.

As is the case with so many war cemeteries, its contemporary serenity belies the frightful events that took place in the immediate surrounds in 1916.

Background to The Battle

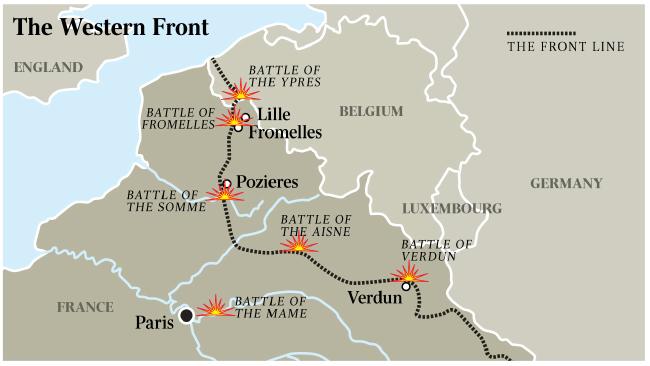

Fromelles is farming hamlet in flat north-western France just 5km from the Belgium border just west of the French town of Lille.

The Battle of Fromelles was a British military assault with allied troops across farmland between the villages of Fromelles and Fleurbaix (means ‘flower meadow‘) on the night of July 19, 1916 in a bid to break through the German’s entrenched positions to the north and south of the Somme River. It was to become swallowed up within the broader Battle of the Somme on the Western Front of The Great War 1914-1918.

The village of Fromelles was captured nearly two years prior during the ‘Race to the Sea‘, when the German advance across northwest Europe was halted by the British and French. The opposing armies had tried to outflank each other, until their frontlines reached Belgium’s North Sea coast.

Fromelles had remained in German hands ever since, nestled behind a long and well-entrenched front line, held in this sector by the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, and further supported by strategically positioned units along Aubers Ridge to the northwest of the village.

The Allied aim for the battle that is about to begin is to deceive German high command into keeping their reserves in place, rather than sending them south to reinforce their units on the Somme, where the mighty Allied offensive is taking place.

Before today, British forces have launched two unsuccessful attacks in the area in front of Aubers Ridge. The first, only two months after German forces occupied the area, was intended to capture the Ridge itself.

Then, in May 1916, more than a year after this first attempt, the British 8th Division sought to seize the German positions before the Ridge.

Despite the artillery’s failure to destroy the German defences, the 8th Division’s infantry advanced and were shot down by German machine gunners. Some 11,000 British soldiers were killed, wounded or listed as missing. After the battle, German soldiers needed an entire week to bury the dead.

So the British had attempted two similar attacks and been twice defeated heavily. The Battle of Fromelles produced much to the same result.

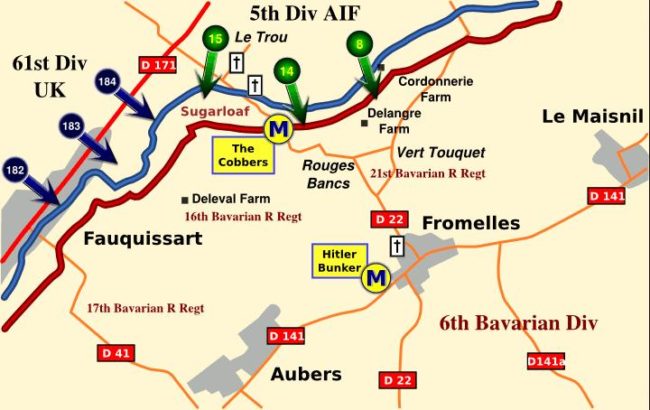

Two weeks hence, the Battle of Fromelles began to unfold on a hazy Wednesday morning, as the British 61st Division and the Australian 5th Division moved into position to launch their attack.

A Snapshot of the Planning

For the prior two days, British artillery fire against German positions had also intensified.

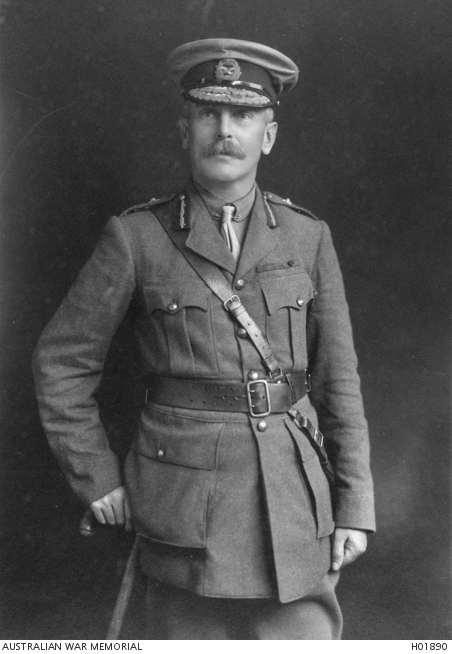

General Richard Haking was the British commander on this part of the front. He believed that the objective, the rear most trench of the enemy’s front line, lay about 140 metres beyond ‘no man’s land’.

No Man’s Land

No Man’s Land

Haking was based at XI Corps HQ in Sailly, 187 km away, and was convinced the objective is achievable by a smaller force than previously imagined.

Into the battle was thrust the Australian 5th Division under the command of the Australian Major-General J. W. McKay along with the British 61st. The plan called for the capture of enemy positions that protected Fromelles.

He decided that one division from 11th Corps, under Major General Colin McKenzie, fight alongside the 5th Australian Division, commanded by Gallipoli veteran Lieutenant General Sir James McCay.

However, the British 61st Division was generally considered to be under-equipped and it will be the 5th Australian Division’s first experience of combat on the Western Front.

Brigadier General Harold “Pompey” Elliott, commander of the Australian 15th Brigade, part of the 5th Division, had great misgivings about the coming attack. Many aspects of the planning, and his experience, suggest to him that the whole operation is inadvisable. Among other things, the Australian artillerymen, whose role would be crucial to the operation’s success were inexperienced and their guns are unreliable. Adding to these concerns, the distance to be covered across no man’s land is highly variable across the line of attack, in some places is up to 400 metres wide.

Much of this ground was waterlogged and in clear view of the German positions, including the Sugarloaf salient, a series of concrete bunkers fortified with machine guns able to fire forward and to each side.

Elliott has took a visiting staff officer from Field Marshal Haig’s headquarters, Major Howard, beyond the front line to a post in no man’s land, where there was a good view of the Sugarloaf.

After showing Howard the plan of attack, the draft orders, and the ground over which the attack was to take place, Elliott asked for the Major’s frank assessment of the likely outcome. he attack on Fromelles, or the Battle of Fleurbaix, was the brainchild of the British General Sir Richard Haking.

Howard predicted “a bloody holocaust”. Elliott urged him to go back to Field Marshal Haig and inform him that Haking’s strategy was flawed. Whether or not Howard was able to do so, remains unclear, but by the morning of the 19th the only result has been a delay in the operation.

British General Haking

British General Haking

Snapshot of the Battle

It’s 6pm and the fourth wave of infantry is advancing. Two and a half hours of daylight remain.

The Allied artillery barrage lifts its range to target the rear of the German line as successive waves of British and Australian troops advance against the enemy’s front line trenches and the salients.

Over The Top

Over The Top

Major Geoff McCrae, a Gallipoli veteran, leads the fourth wave of the 15th Australian Brigade, including the 59th and 60th Battalions – about 2000 men including 60 officers.

His men include signallers with wire and telephones to keep headquarters informed of the battle’s progress.

75 metres into no man’s land, McCrae is shot in the neck and killed. All McCrae’s signallers also fall dead or wounded. Messages now have to be to be carried back across no man’s land by runners.

Private Walter ‘Jimmy’ Downing of 57th Battalion is watching the attack unfold.

“The 60th climbed on to the parapet, heavily laden, dragging with them scaling ladders, light bridges, picks, shovels and bags of bombs.

“Scores of stammering German machine-guns spluttered violently, drowning the noise of the cannonade. The air was thick with bullets, swishing in a flat lattice of death. There were gaps in the lines of men – wide ones, small ones. The survivors spread across the front, keeping the line straight… The bullets skimmed lo, from knee to groin, riddling the tumbling bodies before they touched the ground. Still the line kept on.

“Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid, like great rows of teeth knocked from a comb, but still the line went on, thinning and stretching. Wounded wriggled into shell holes or were hit again. Men were cut in two by streams of bullets. And still the line went on… It was the charge of the Light Brigade once more, but more terrible, more hopeless.”

A mere ten minutes have passed since 6pm.

With parts of the German front line trenches being captured by both British and Australian units, the soldiers press their attack and move on towards the German second line.

53rd Battalion commander Lt. Col. Ignatius Norris arrives with battalion headquarters in the fourth wave, calling ‘Come on lads! Only another trench to take!’

Men of the 53rd Battalion in a trench in their front line a few minutes before the launching of the attack at Fromelles

As Norris moves forward he is cut down by an ‘unsuppressed machine gun’. Norris’s last words are reported to be, ‘Here, I’m done, will somebody take my papers?’ With him is Private Leslie Croft, a battalion signaller, who attempts unsuccessfully, with others, to bring his wounded leader back to safety.

Others with Norris are also killed and wounded by German machine guns, including his young adjutant, 32-year-old Lieutenant Harry Moffitt.

According to Sergeant Patrick Lonergan, when he sees his colonel hit, Moffitt instantly calls for four men to carry him back to the Australian lines. As he does so, he too is hit and falls dead across Norris’ body.

A little before half past six 53rd and 54th Battalion soldiers who are now occupying the German front line from Rouges Banc to near Delangre Farm press forward in an attempt to locate the key objective, the German second line.

Some of these men are further than 300 metres but only find occasional enemy soldiers taking cover in shell craters, many of whom retreat on sight. The Australian soldiers are under orders to resist the chase, instead some Germans are taken prisoner and sent back to Australian lines.

Lieutenant Colonel Toll, commanding the 31st Battalion also looks for and is unable to find the German second line. Toll later reported, “(We) swept on with the intention of capturing the second and third trenches in the first line system, but…no trace could be found… It now appeared evident that the information supplied as to enemy defences…was incorrect and misleading. The ground was flat, covered with fairly long grass, the trenches shown on aerial photos were nothing but ditches full of water.”

By 6:45, the Australian and British advance is stalled and turns into a retreat under fire from their own artillery as the guns continue to hit targets behind the enemy’s front line, unaware of the progress of the infantry units.

German artillery also begins to open up on no man’s land, preventing other Allied units from advancing.

By around twenty past seven, Brigadier-General Elliott sends a report to Headquarters that the attack is failing in part because of a lack of support.

In response, Major General McCay sends about 500 men, half of the reserve 55th Battalion, into the battle.

But as 8pm approaches, the Germans are reoccupying much of their front line. The Allied attack is failing everywhere.

The German record of battle reports that “the forward trench was once again in our hands – 47 unwounded and 14 wounded Englishmen were captured, as well as seven machine guns and sundry material.

A great number of wounded and dead English lay in front of our position. Bandages were ordered forward, the platoons which had been pushed out moved back into their positions…two captured machine guns were turned against the enemy.”

And so it would be, July 19, the 24 hours often described as the “worst day in Australian military history” and a cruel blink in time that saw 5533 casualties including 2000 dead.

Initially called the Battle of Fleurbaix, then later formally titled The battle of Fromelles, but it was cynically dismissed by surviving soldiers as “that Fleurbaix stunt” by British General Haking.

The battle marked Australia’s entry onto the Western Front of the Great War. It came at great cost, characterise as a legacy battle of attrition involving loss of life on an epic scale. Men in their hundreds of thousands fell on the Somme battlefields, most the victims of duelling artillery and eviscerating machine gun fire.

Australian Imperial Force in Egypt before embarking for the Western Front

Australian Imperial Force in Egypt before embarking for the Western Front

Lest We Forget

Lest We Forget