“I did what was right and I stand by it.”

(Constance Georgine Markievicz).

(Constance Georgine Markievicz).

|

William Butler Yeats’ epic poem after the Easter Rising of 1916 famously wrote “MacDonagh and MacBride and Connolly and Pearse now and in time to be, wherever green is worn, are changed, changed utterly. A terrible beauty is born.”

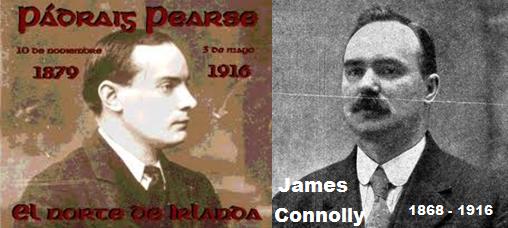

The audacity and bravery of just over 1200 combined Irish Republican Brotherhood Volunteers, led by Padraig Pearse, and Irish Citizen Army Volunteers, led by James Connolly, which on Easter Monday 1916 merged to form the Irish Republican Army, unleashing an armed rising in Dublin against the ruling colonial British state at the time has not been equalled.

Easter, 1916

“I have met them at close of day

Coming with vivid faces

From counter or desk among grey

Eighteenth-century houses.

I have passed with a nod of the head

Or polite meaningless words,

Or have lingered awhile and said

Polite meaningless words,

And thought before I had done

Of a mocking tale or a gibe

To please a companion

Around the fire at the club,

Being certain that they and I

But lived where motley is worn:

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

That woman’s days were spent

In ignorant good-will,

Her nights in argument

Until her voice grew shrill.

What voice more sweet than hers

When, young and beautiful,

She rode to harriers?

This man had kept a school

And rode our winged horse;

This other his helper and friend

Was coming into his force;

He might have won fame in the end,

So sensitive his nature seemed,

So daring and sweet his thought.

This other man I had dreamed

A drunken, vainglorious lout.

He had done most bitter wrong

To some who are near my heart,

Yet I number him in the song;

He, too, has resigned his part

In the casual comedy;

He, too, has been changed in his turn,

Transformed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Hearts with one purpose alone

Through summer and winter seem

Enchanted to a stone

To trouble the living stream.

The horse that comes from the road.

The rider, the birds that range

From cloud to tumbling cloud,

Minute by minute they change;

A shadow of cloud on the stream

Changes minute by minute;

A horse-hoof slides on the brim,

And a horse plashes within it;

The long-legged moor-hens dive,

And hens to moor-cocks call;

Minute by minute they live:

The stone’s in the midst of all.

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

O when may it suffice?

That is Heaven’s part, our part

To murmur name upon name,

As a mother names her child

When sleep at last has come

On limbs that had run wild.

What is it but nightfall?

No, no, not night but death;

Was it needless death after all?

For England may keep faith

For all that is done and said.

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

I write it out in a verse –

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.”

by William Butler Yeats – Irish Poet (1865-1939)

Easter, a hundred years ago saw the Easter Rising (Éirí Amach na Cásca) – an armed people’s insurrection in Dublin, Ireland during Easter.

The Rising was launched by Irish nationalists in a bid to end British rule over Ireland and calling for an independent Irish Republic.

The Easter Rising was indeed the catalyst for the creation of an independent Irish State, which is what we have today.

Led by schoolmaster and Irish language activist Patrick Pearse, and joined by the smaller Irish Citizen Army of James Connolly and 200 Irish Volunteers, the Easter Rising began on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, and lasted for six days.

But the British Army, with vastly superior numbers and artillery during The Great War, quickly suppressed this Irish Rebellion.

Pearse, under imminent threat by the British of an artillery massacre upon civilian Dubliners, surrendered on Saturday 29 April. After the surrender 3,500 local Irish were taken prisoner by the occupying British, many of whom played no part in the Rising. Some 1,800 Irish were sent to internment camps or prisons over in Britain. Most of the leaders of the Rising were executed following kangaroo courts-martial.

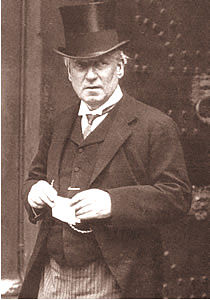

Typically, one narcissist politician was Britain’s imperial protagonist bullying the neighbouring Irish at the time, Britain’s PM, an upstart Yorkshire lawyer, Herbert Henry Asquith, and a drunk who hated the Irish. Asquith personally placed all of Ireland under martial law. Asquith personally was the instigator of the invasion Home Rule Act, and it was he who should have been assassinated.

Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) – infamous dictator, mass murderer, narcissist, drunk, British PM

Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928) – infamous dictator, mass murderer, narcissist, drunk, British PM

It was the wrong thing for Britain to dominate, persecute and murder the Irish. Many ‘troubles’ have since ensued. The consequences went culturally deep and inter-generationally, pervading to today and beyond. Asquith and Thatcher were both Tory elitists.

Tower Bridge would have been better adorned…

Constance Georgine Markievicz was incarcerated in Holloway prison in 1918 during which time she was elected to parliament.

Meaning of the Easter Rising

The men and women of the 1916 Rising envisaged a new Ireland as a national democracy; an Ireland which, in the words of the Proclamation, ‘guarantees religious and civil liberty, equal rights and equal opportunities to all its citizens, and [which] declares its resolve to pursue the happiness and prosperity of the whole nation and all of its parts, cherishing all of the children of the nation equally.’ They believed that this could only be achieved through complete independence.

When they seized the General Post Office in Dublin on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, the leaders of the Rising proclaimed a free Irish Republic in which the egalitarian idea was centrally enshrined. The Proclamation, which was first read out by Patrick Pearse on the steps of the GPO just after noon, declared the rights of the people of Ireland to be sovereign. It looked forward to the establishment of a native Government elected on the democratic principles of self-determination and government by consent.

The 1916 rising set in train an unstoppable process which led to the separation of Ireland from Great Britain.

Australian Army service men and women will recognise the significance of this Irish Republican Brotherhood logo of 1858. Most traditional Australians (1788-1901) have Irish ancestry. It is the Easter Rising

Australian Army service men and women will recognise the significance of this Irish Republican Brotherhood logo of 1858. Most traditional Australians (1788-1901) have Irish ancestry. It is the Easter Rising

The motto of the gold rising sun on a green landscape is ‘ɛrɪn ɡə ˈbrɑ, or Éirinn go Brách, or in English:

“Ireland Forever“…

Australia’s Irish heritaged Ned, Dan and Ellen Quinn Kelly would all be very proud.

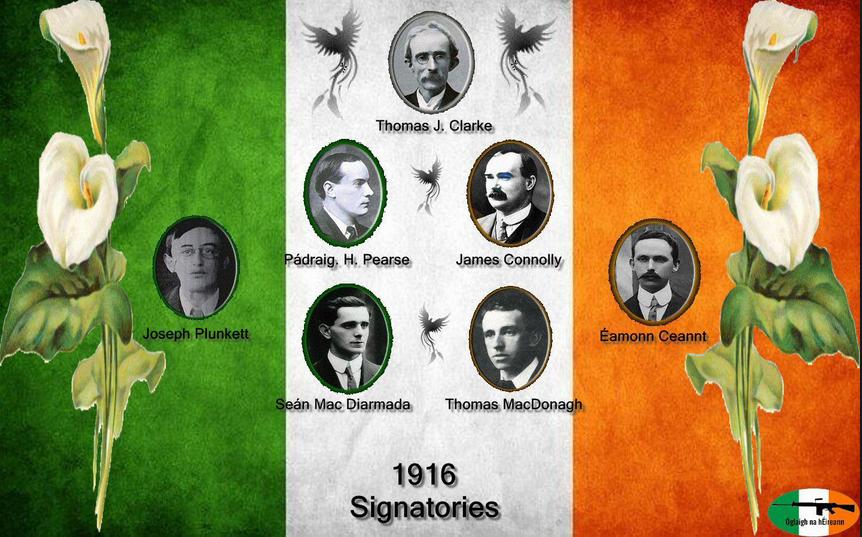

The Executed Leaders of the 1916 Rising

The Seven Signatories:

Éamonn Ceannt: Born in Galway in 1881, prior to the Rising Ceannt was an employee of the Dublin Corporation. He was a co-founder of the Irish Volunteers, partaking in the successful Howth gun-running operation of 1914. His involvement in republican activities was complemented by his interest in Irish culture, specifically Irish language and history, although he was also an accomplished uileann piper.As the commander of the Fourth Battalion of Irish Volunteers during the Rising, he took possession of the South Dublin Union, precursor to the modern-day St. James’s Hospital. He was executed on 8 May 1916.

Thomas James Clarke: Born on the Isle of Wight in 1857, Clarke’s father was a soldier in the British army. During his time in America as a young man, he joined Clann na nGael, later enduring fifteen years of penal servitude for his role in a bombing campaign in London, 1883-1898. In 1907, having returned from a second sojourn in America, his links with Clan na nGael in America copper-fastened his importance to the revolutionary movement in Ireland. He held the post of Treasurer to the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and was a member of the Supreme Council from 1915. The first signatory of the Proclamation of Independence through deference to his seniority, Clarke was with the group that occupied the G. P. O. He was executed on 3 May 1916.

James Connolly (1868-1916): Born in Edinburgh in 1868, Connolly was first introduced to Ireland as a member of the British Army. Despite returning to Scotland, the strong Irish presence in Edinburgh stimulated Connolly’s growing interest in Irish politics in the mid 1890s, leading to his emigration to Dublin in 1896 where he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party. He spent much of the first decade of the twentieth century in America, he returned to Ireland to campaign for worker’s rights with James Larkin. A firm believer in the perils of sectarian division, Connolly campaigned tirelessly against religious bigotry. In 1913, Connolly was one of the founders of the Irish Citizen Army. During the Easter Rising he was appointed Commandant-General of the Dublin forces, leading the group that occupied the General Post Office. Unable to stand to during his execution due to wounds received during the Rising, Connolly was executed while sitting down on 12 May 1916. He was the last of the leaders to be executed.

Seán MacDiarmada: Born in 1884 in Leitrim, MacDiarmada emigrated to Glasgow in 1900, and from there to Belfast in 1902. A member of the Gaelic League, he was acquainted with Bulmer Hobson. He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1906 while still in Belfast, later transferring to Dublin in 1908 where he assumed managerial responsibility for the I. R. B. newspaper Irish Freedom in 1910. Although MacDiarmada was afflicted with polio in 1912, he was appointed as a member of the provisional committee of Irish Volunteers from 1913, and was subsequently drafted onto the military committee of the I. R. B. in 1915. During the Rising MacDiarmada served in the G. P. O. He was executed on 12 May 1916.

Thomas MacDonagh: A native of Tipperary, born in 1878, MacDonagh spent the early part of his career as a teacher. He moved to Dublin to study, and was the first teacher on the staff at St. Enda’s, the school he helped to found with Patrick Pearse. MacDonagh was well versed in literature, his enthusiasm and erudition earning him a position in the English department at University College Dublin. His play When the Dawn is Come was produced at the Abbey theatre. He was appointed director of training for the Irish Volunteers in 1914, later joining the I. R. B. MacDonagh was appointed to the I. R. B. military committee in 1916. He was commander of the Second Battalion of Volunteers that occupied Jacob’s biscuit factory and surrounding houses during the Rising. He was executed on 3 May 1916.

Patrick Pearse: Pearse was born in Dublin in 1879, becoming interested in Irish cultural matters in his teenage years. In 1898 Pearse became a member of the Executive Commmittee of the Gaelic League. He graduated from the Royal University in 1901 with a degree in Arts and Law. Pearse’s literary output was constant, and he published extensively in both Irish and English, becoming the editor of An Claidheamh Soluis, the newspaper of the Gaelic League. He was a keen believer in the value of education, and established two schools, Coláiste Éanna and Coláiste Íde, devoted to the education of Irish children through the Irish language. One of the founder members of the Irish Volunteers, and the author of the Proclamation of Independence, Pearse was present in the G. P. O. during the Rising, and was Commander in Chief of the Irish forces. He was executed on 3 May 1916.

Joseph Mary Plunkett: Born 1887 in Dublin, son of a papal count, Plunkett was initially educated in England, though he returned to Ireland and graduated from U. C. D. in 1909. After his graduation Plunkett spent two years travelling due to ill health, returning to Dublin in 1911. Plunkett shared MacDonagh’s enthusiasm for literature and was an editor of the Irish Review. Along with MacDonagh and Edward Martyn, he helped to establish an Irish national theatre. He joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913, subsequently gaining membership of the I. R. B. in 1914. Plunkett travelled to Germany to meet Roger Casement in 1915. During the planning of the Rising, Plunkett was appointed Director of Military Operations, with overall responsibility for military strategy. Plunkett was one of those who were stationed in the G. P. O. during the Rising. He married Grace Gifford while in Kilmainham Gaol following the surrender and was executed on 4 May 1916.

Other executed leaders:

Roger Casement: Born in 1864 in Dublin, Casement was knighted for his services to the British consulate. He campaigned tirelessly to expose the cruelty inflicted on native workers in the Belgian Congo in 1904, and again in Brazil from 1911-1912, causing an international sensation with his reportage. Casement had become a member of the Gaelic League in 1904, beginning at that time to write nationalist articles under the pseudonym ‘Seán Bhean Bhocht’. He retired from the British consular service in 1913, after which he joined the Irish Volunteers. Casement was despatched to Germany on account of his experience to raise an Irish Brigade from Irish prisoners of war. He was captured in Kerry in 1916 on Good Friday having returned to Ireland in a German U-Boat. Casement was imprisoned in Pentonville Gaol in London, where he was tried on charges of High Treason. He was hanged on 3 August 1916, the only leader of the Rising to be executed outside of Ireland.

Con Colbert: Born in 1888, Colbert was a native of Limerick. Prior to the Easter Rising he had been an active member of the republican movement, joining both Fianna Éireann and the Irish Volunteers. A dedicated pioneer, Colbert was known not to drink or smoke. As the captain of F Company of the Fourth Battalion, Colbert was in command at the Marrowbone Lane distillery when it was surrendered on Sunday, 30 April 1916. His execution took place on 8 May 1916.

Edward Daly: Born in Limerick in 1891, Daly’s family had a history of republican activity; his uncle John Daly had taken part in the rebellion of 1867. Edward Daly led the First Battalion during the Rising, which raided the Bridewell and Linenhall Barracks, eventually seizing control of the Four Courts. A close friend of Tom Clarke, their ties were made even stronger by the marriage of Clarke to Daly’s sister. Daly was executed on 4 May 1916.

Seán Heuston: Born in 1891, he was responsible for the organisation of Fianna Éireann in Limerick. Along with Con Colbert, Heuston was involved in the education of the schoolboys at Scoil Éanna, organising drill and musketry exercises. A section of the First Battalion of the Volunteers, under the leadership of Heuston, occupied the Mendicity Institute on south of the Liffey, holding out there for two days. He was executed on 8 May 1916. Heuston Railway station in Dublin is named after him.

Thomas Kent: Born in 1865, Kent was arrested at his home in Castlelyons, Co. Cork following a raid by the Royal Irish Constabulary on 22 April 1916, during which his brother Richard was fatally wounded. It had been his intention to travel to Dublin to participate in the Rising, but when the mobilisation order for the Irish Volunteers was cancelled on Easter Sunday he assumed that the Rising had been postponed, leading him to stay at home. He was executed at Cork Detention Barracks on 9 May 1916 following a court martial. In 1966 the railway station in Cork was renamed Kent Station in his honour.

John MacBride: Born in Mayo in 1865. Although he initially trained as a doctor, MacBride abandoned that profession in favour of work with a chemist. He travelled to America in 1896 to further the aims of the I. R. B., thereafter travelling to South Africa where he raised the Irish Transvaal Brigade during the Second Boer War. MacBride married the Irish nationalist Maude Gonne in 1903. He was not a member of the Irish Volunteers, but upon the beginning of the Rising he offered his services to Thomas MacDonagh, and was at Jacob’s biscuit factory when that post was surrendered on Sunday, 30 April 1916. He was executed on 5 May 1916.

Michael Mallin: A silk weaver by trade, Mallin was born in Dublin in 1874. Along with Countess Markievicz, he commanded a small contingent of the Irish Citizen Army, of which he was Chief of Staff, taking possession of St. Stephen’s Green and the Royal College of Surgeons. He was executed on 8 May 1916.

Michael O’Hanrahan: Born in Wexford in 1877. As a young man, O’Hanrahan showed great promise as a writer, becoming heavily involved in the promotion of the Irish language. He founded the first Carlow branch of the Gaelic League, and published two novels, A Swordsman of the Brigade and When the Norman Came. Like many of the other executed leaders, he joined the Irish Volunteers from their inception, and was second in command to Thomas MacDonagh at Jacob’s biscuit factory during the Rising, although this position was largely usurped by the arrival of John MacBride. His execution took place on 4 May 1916.

William Pearse: Born in 1881 in Dublin. The younger brother of Patrick, William shared his brother’s passion for an independent Ireland. He assisted Patrick in running St. Enda’s. The two brothers were extremely close, and fought alongside each other in the G. P. O. William was executed on 4 May 1916. Pearse railway station on Westland Row in Dublin was re-named in honour of the two brothers in 1966.

In hindsight, they all could have assassinated Asquith et al.

Read More:

http://www.easter1916.ie/index.php/people/a-z/countess-constance-markievicz/