Winter is approaching Australians and once again the religious charity The Salvation Army exploits community generosity through its annual Red Shield Appeal requesting generous donations.

The Salvation Army tells us that it needs millions of cash in donations to go towards caring for the desperate needs of the poor and most vulnerable in our society, especially our children. The Salvos community appeal message is to be part of transforming the lives of people right around the country.

Mostly that has been faithfully true, but recent revelations have revealed diversion of Salvo’s resources to supporting Green-Labor’s illegals instead of to ‘as-promised’ Australians. The current Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse has further revealed a dark criminal and wicked pedophilia culture across The Salvos.

Last Red Shield Appeal in 2013 when the Welsh Moll Gillard was running riot, we warned Australians to be wary of the Salvos:

Salvation Army diverting charity to illegals

The Salvos acknowledge on their website that during a Leftist Gillard regime, they accepted $75 million in Australian taxpayers money to provide “humanitarian support services for asylum seekers in the Nauru and Manus Island Offshore Processing Centres (OPCs) from August 2012 until February 2014.”

Politically, The Salvation Army does not support mandatory detention or the offshore processing of asylum seekers. It has persued its missionary zeal to provide its services in places where there is suffering or need. “This is something we have done for 150 years.”

So the Salvos have regressed to their colonial missionary zeal and stepped outside Australia into the realm of World Vision, UNICEF and Oxfam, without Australian donors being aware.

On Nauru and Manus Island, the Salvation Army’s Humanitarian Mission Services have since 2012 provided Green-Labor’s economic illegals with educational and recreational opportunities (computer skills training), emotional psychological support, English language training and gym activities, as well as organising cultural events, outings and excursions and sporting events.

What 5 star health resort anywhere in Australia offers this?

Does The Salvation Army advocate for the needs of asylum seekers? “Yes. We have advocated for an improvement in facilities at both sites and these requests have been made known to the relevant domestic and Australian authorities. The Salvation Army advocates for the development of proactive, compassionate and appropriate human rights focused policies in relation to all asylum seekers.”

Then we have the current Royal Commision expose of pedophile Salvos abusing Australian children in their care going back decades.

Last month in April 2014, The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Abuse heard that Major Colin Haggar of the Salvation Army allegedly told the parents of an eight or nine-year-old girl that he had sexually abused their daughter, saying he was glad to have spoken to them and “now … can go out and save more souls.”

As recently as July last year, Haggar was working as the director of a crisis centre offering accommodation for vulnerable women and children, despite the Army receiving several other alleged abuse complaints against him.

The Salvation Army also dismissed two Salvo whistleblowers from their positions at a home in Queensland after they reported another alleged instance of abuse towards boys in the Alkira Salvation Army home at Indooroopilly in 1975.

Around 1,500 Australians have so far spoken about what happened to them. More than 1,000 others are on a ballooning waiting list, which grows by an extra 40 people each week.

Some are in their 80s and 90s, and many have carried their secrets for a lifetime. Their stories are not treated as legal evidence, their claims are not tested – as in a court of law. But they are believed and their trauma acknowledged. So far, out of the royal commission’s private hearings, 156 cases have been referred to the police for investigation.

But lawyers say despite government and institutional apologies for the so-called sins of the past, the abuse of children in care is not confined to the past, it is still happening. Child abuse experience kept secret for decades.

Ray Prosser never told his wife of 40 years he was raped as a boy. She died more than a decade ago not knowing of the secret he had carried from his time at the Salvation Army-run Box Hill Home for Boys.

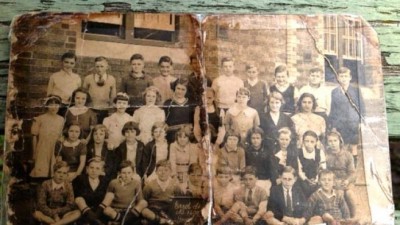

A 1938 school photo includes Ray Prosser

with his grade-five class from Errol Street State School.

A 1938 school photo includes Ray Prosser

with his grade-five class from Errol Street State School.

He was 10 when Proser says he was abused in the showers by a man he knew only as Envoy Ashley. Now a few months shy of 86, Mr Prosser has told his story to the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in a private session in Melbourne.

He spoke to the ABC on the eve of the hearing and explained he was put into care by his mother at six months of age after his parents separated. He was sent to Box Hill in 1938 at the age of 10 and says it was at times a brutal experience.

“Envoy Ashley was the man who did the damage,” Mr Prosser said. “Putting it bluntly, he raped me. Some of us boys used to wet the bed, just one of those things in life, and he’d come round on night duty and if you wet the bed he’d take you down to the showers and put you through the showers with cold water.

“He’d rub you all down with a rough towel to dry you off and then start fiddling with you and one thing and another, and being that age of life I didn’t know what was going on or anything.”

Mr Prosser says he told no-one about the abuse but just “got on with things”. “Who do you tell?” he said. “It was in my mind but there was no-one to talk to. You didn’t discuss things.”

More than 50 years later, Mr Prosser says he “confronted” his alleged perpetrator after hearing through a friend he was involved in the Salvation Army’s Dandenong Corps in Victoria.

He turned up for a Wednesday night meeting and sat down beside him.

“I said, ‘I know you, your name’s Envoy Ashley’,” said Mr Prosser, recounting his exchange now 25 years ago.

“‘Yes’, he said to me, all smiles. “I said, ‘You were at Box Hill Boys Home between 1938 and 1942’. “He said, ‘Yeah, that’s right’.

“I said, ‘You still don’t know me?’. He said, ‘no’. “I said, ‘Well, I know you very well. My name’s Ray Prosser but you would have known me while I was there as Ray Elliott’.

“He just turned his back on me and wouldn’t speak to me anymore, and I thought well I’ve got the right man, there’s no two ways there.”

Mr Prosser says he never directly challenged him about what had happened at the boy’s home, and he never went to the police with his allegations, which he now regrets.

However, the Salvation Army paid Mr Prosser $23,000 several years ago for the abuse he suffered, an amount he describes as “chicken feed”.

The ABC can reveal Envoy Ashley was in fact Leonard Victor Ashley, who died in 1993 at the age of 91.

The Salvation Army says there are no written records of his time at the Box Hill boys home because very few employee records exist for those who worked in its children’s homes in the 1930s and 1940s.

It says it kept proper employment records only for ordained officers.

It also says there were no other complaints recorded by other Box Hill residents against Ashley, but it “fully takes the word of the survivor in the complaint process”.

The Salvation Army says Ashley’s funeral took place at the Dandenong Salvation Army, where he sometimes attended but was not a “soldier”. ‘They didn’t care where they belted you’

At 91, Mary Heather Lane is one of the oldest to attend a private session of the royal commission.

The Perth resident was originally from New South Wales and lived in two Catholic orphanages in Sydney, where she was placed by her mother from the age of seven.

They included Mater Dei orphanage at Narellan in the city’s south-west and St Magdalen’s Retreat at Tempe, where she says she “worked all day every day”, except Sunday, in the laundry.

She says she was not sexually abused but was subjected to routine physical beatings. She describes being whipped with a bamboo cane “for the least little thing” and on all parts of her body.

“I made a little doll’s dress once, a little gold one, and I piped it with black. This nun said to me, they were very cruel people the nuns, and she said, ‘You don’t put black with gold, you know’, and I said, ‘you do, it looks lovely’.

“I got a belting out of that … and they didn’t care where they belted you. So where did they belt you?

Anywhere … with the cane, on the shoulder, on the bottom … you got belted anywhere.”

Ms Lane says the abuse was also psychological.

“They used to say to me, ‘your mother is dead’. “And then one day, a good while later, they said, ‘Mary Lane, you’ve got a visitor’, and I thought I don’t know anybody, and they said, ‘It’s your mother’, and I thought, she’s dead.”

Ms Lane describes going up to the garden “where the nuns used to live” to meet her mother, whom she did not recognise.

“She’s sitting on the seat and I said, ‘Are you Mrs Lane?’, and she said, ‘Yes, aren’t you going to kiss me?’.

“But I was too shy, you know, I was a shy kid really.”

_And they lied to you about her … how did you feel?_

“Oh, I think everything was a lie. I look back and see a lot of things were lies … that’s the one thing I drummed into my son about lies – don’t tell lies, ever.”

She recalls the punishment meted out by two nuns at the Tempe orphanage who accused her of not sweeping under her bed.

“They sat on me and cut my hair off. The nun sat on my tummy, the other one held my feet, and they just cut my hair right off because I had lovely long hair, and they used to say, ‘all you think about is looking after your hair’, and I think they were jealous.

“Then they locked me in a toilet. We used to have to sit in this little toilet shed with a toilet seat but no pan and that’s what it was.

“My mother came to see me and she didn’t know that I’d been moved to Tempe, and she came to see me and I wouldn’t go up.

“It wasn’t that I didn’t want to go up to see her, it was that I felt ashamed not having any hair.”

The Royal Commission is being overwhelmed with requests from victims for private sessions. Around 1,500 people have sat before a royal commissioner who bears witness on behalf of the nation to their accounts of abuse.

Royal commission chief executive Janette Dines says the waiting list includes 1,000 more and is ever-growing.

“The reality at the moment is that if the rate of demand continues, when the commission ends at the end of 2015 there will be around 2,000 people who would miss out on a private session,” she said.

“We’re certainly very aware that once people make the decision to come to a private session and speak to a royal commissioner that it’s a very significant moment in their life. We’re also aware from support and advocacy groups that there’s a level of anxiety existing now both about the delay in receiving a private session and also the prospect that some people might miss out.”

“We think it’s very, very important that everyone who wants to come to a private session has a chance to do so, and that’s why we’d put a lot of effort into making people aware of the option to have a private session.”

Ms Dines says so far 156 cases of abuse raised in the private sessions have been referred to police around the nation for investigation.

“Sometimes the person who comes to a private session might not be aware that what happened to them was a criminal matter and could be looked at by police.”

She says the referral does not have to be done with the agreement of the victim.

“If the royal commission believes there’s a significant risk of harm occurring to someone or if a crime is occurring, they would always refer that matter to the police.”

The royal commission says some of the cases handed to police to examine do involve “contemporary” claims of abuse.

Melbourne lawyer Angela Sdrinis, a partner with Ryan Carlisle and Thomas, has been inundated with complaints from sex abuse victims and says the allegations are not all in the past.

“We’re seeing a lot of older people coming forward, but we’re also seeing younger people coming forward, some who are still in the system and that’s unusual; people who are being abused as we speak, usually very raw, very damaged,” she said.

“We know the nature of childhood sexual abuse is that it usually takes people decades to come forward, but I think what the royal commission has done is that it’s given people permission to come forward and tell their stories.”

Ms Sdrinis says the current claims involve children in foster care and residential care and have either been investigated by police or are under investigation.

The youngest victim is a 15-year-old girl.

“It’s not in the past, and you’re never going to have a perfect system certainly when there are budgetary considerations,” she said.

“I think the systems are a lot better than they were in the past, and one of the things that will hopefully come out of the royal commission are ways in which organisations can do things better.

“But the abuse of children in care is still happening.” ‘Don’t take your abuse story to the grave’

But for the oldest abuse victims, the chance to see their perpetrators brought to justice has gone. They have died, taking their secrets with them.

Leonie Sheedy, head of one of the nation’s highest profile victims support groups, the Care Leavers Australia Network (CLAN), has been encouraging this group of survivors to take their stories to the royal commission’s private sessions.

She has travelled from state to state to be beside some of them as their chosen support person.

“Many of the people I’ve spoken to over the last 14 years have said, ‘I don’t remember their names or the years it happened or the orphanage name that it happened at, and it’s no use going to the police because I don’t have the information or they’ll be long dead’,” Ms Sheedy said.

“I always say to them it’s important to share your story because you might help to put a piece of the jigsaw puzzle of an abuser who worked in one orphanage and then he was transferred to another and abused other children.

“We need to create a paper trail, and I always tell elderly people don’t take your abuse story to the grave because it won’t do anyone any good in the coffin.”

Mr Prosser was among the many Ms Sheedy convinced to speak out. Now he is urging others in their final years to do the same.

“I think everyone should be able to tell their story about what they did to us as kids,” he said.

“It should never have happened, and I would say let’s hope it never happens again, though I would also say there’s plenty of abuse going on nowadays too. “If I can do it, you can do it. I was frightened for a while, but do it now while you’ve got the chance. Tomorrow might be too late.”

Thank God for the Salvos abuse of Australian trust? So what does this maketing mean and where do the donations really go?

The Salvos creed is “We believe in the immortality of the soul, the resurrection of the body, in the general judgement at the end of the world, in the eternal happiness of the righteous, and in the endless punishment of the wicked.”

It means nothing. The Salvos have lost all legitimate meaning.

Better that Australians cast the Salvos to history and instead morally support The Smith Family, committed to genuinely caring for Australia’s neglected and vulnerable children.

The Smith Family is a national, independent children’s charity helping disadvantaged Australians to get the most out of their education, so they can create better futures for themselves.