Foreigner, Tim Soutphommasane, PM Kevin Rudd’s last-minute installed Commissioner for Foreigner Favours, sips a double espresso looking over the vast playing fields of his alma mater, the University of Sydney, on a languorous spring afternoon.

But then at Sydney Uni its all descended to “Spot the Aussie” – but Uni ethno policy is now cashed up Asian Rules!

Remember the days when someone would jokingly say ‘Spot the Aussie’? It used to be a joke but these days it has become a sad reality with so many cities and suburbs over-run with third world intruders, making many Australians feel uncomfortable at becoming a minority in their own suburb. Read More: http://www.partyforfreedom.com.au/2014/06/22/spot-the-aussie/

The French-born, southwest Sydney-raised son of Lao parents has just returned after five years in England and is carefully considering what it means to be Australian.

“I have conversations all the time about Australian-ness,” he says. “And every time, someone says, ‘Look, I don’t see what the fuss is about. Being Australian is about loving sport, the beach and having a good time’. And I always say, ‘No, actually, it’s not’.”

Dr Soutphommasane was appointed by the Labor government a month before the September 2013 national election to oversee Labor’s Racial Discrimination Act. Such an appointment was to perpetuate Labor’s multiculturalism while out of office.

Soutphommasane has spent much of his life considering the question of Australianness. “I’ve had to negotiate my own cultural distinctiveness with the idea of Australianness,” says the 27-year-old. “During the 1990s, many wouldn’t have considered me to be Australian, and for a long time I had to ask myself whether I thought of myself as Australian. If we mean by Australian, one’s cultural ancestry or heritage, then I don’t think I would qualify. But if we think of being Australian as subscribing to a set of values, belonging to a tradition of aspiring to standards about how we should conduct our lives together, then I think I’m very Australian.”

For the past five years, Soutphommasane has looked deeply into the heart of nationhood. He has just completed a doctorate on patriotism, citizenship and culture at Oxford University. Now the scholar, who joined the Australian Labor Party at 15 and the speechwriting staff of former NSW premier Bob Carr at 21, has released Reclaiming Patriotism: Nation-Building for Australian Progressives (Cambridge University Press).

It is a patriotic manifesto, of sorts, targeted squarely at the left. It is time for progressives “to stand up for an Australian public culture and civic history”, argues Soutphommasane, and a moderate, small “l” liberal model of national pride.

His book comes as the nation catches its breath after more than a decade of conservative rule and a government that branded its own style of patriotism. Former prime minister Howard’s 2001 Tampa election catchcry–”We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come”–in many ways succinctly sums up its direction.

His book comes as the nation catches its breath after more than a decade of conservative rule and a government that branded its own style of patriotism. Former prime minister Howard’s 2001 Tampa election catchcry–”We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come”–in many ways succinctly sums up its direction.

Justin Di Lollo, Soutphommasane’s mentor and former employer at the Labor-leaning political lobby firm Hawker Britton, says now is “a great time for a young leftie intellectual to come out with something that really challenges those of us that are a bit more rusted on in terms of the Howardesque realpolitik.

“And it’s creating some challenges,” he adds.

https://www.aclu.org/reform-patriot-act

https://www.aclu.org/reform-patriot-act

In his book ‘Reclaiming Patriotism’, Soutphommasane borrows United States ideas and argues that it is the right that has dictated the concept of patriotism for far too long, effectively shaming the left into silence. He contends that many progressives saw Howard’s key policies–from introducing citizenship tests for new immigrants to the “South Pacific solution” for refugees–as a form of “dog whistling”, targeting messages to particular groups of voters that would, for most people, remain unheard.

“I have held a long, lingering frustration with the left liberal response to Howard’s politics because they saw all indications of national solidarity as a form of dog whistling,” says Soutphommasane. “If you were to talk about citizenship, it was dog whistling; national values, dog whistling. Just even the idea of being proud of being Australian was seen as dog whistling.”

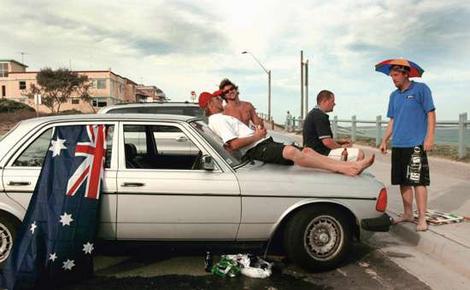

He says many ran away from the concept of patriotism under the Howard government for fear it “would collapse into white Australia racism or cultural chauvinism”. And the 2005 Cronulla “race riots” gave the left further reasons to retreat.

“The Cronulla episode offered a vindication of liberal concern about patriotism,” he says. “The left vacated the field and allowed the right to claim ownership of national values. After that, patriotism became either a form of fascist narcissism–the idea of draping yourself in the flag, tattooing your flesh with the Southern Cross–or a neoconservative patriotism, associated with a right-wing America that celebrated militarism.”

Cronulla, he contends, could have been an opportunity for the left to bring often-fraught issues of national identity and race into the open and back onto temperate ground. Instead, progressives remained silent. “It’s similar to what happened with Tampa,” he says. “The left just had no response.”

In Reclaiming Patriotism, Soutphommasane urges progressives to champion a positive patriotism–with all its symbols, including the flag–as its own. His model does not turn its back on Australia’s history–acknowledging the bad with the good–and it aims to build national solidarity through core values of mateship, fairness and egalitarianism. It thrives on unity, not divisiveness, and is not superior. It also embraces some of the cornerstones of Howard’s patriotic emblems.

“National myths are important and Anzac can be a powerful metaphorical story for Australians,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be about whether your grandparents were there. My grandfathers were in Laos on the banks of the Mekong when World War I was fought. In fact, they would have been excluded from Australia by the White Australia Policy. But I still think Anzac can be a very powerful unifying myth.”

Tim Soutphommasane’s notion of patriotism also demands a great deal from its citizens. “I don’t think civic responsibilities extend to just turning up to your local school on a Saturday every few years and voting,” he says. “[They] go further than that. They involve a tolerance of citizens’ preparedness to deliberate on questions of public concern and a readiness to make sacrifices for others.”

And while many would regard dual citizenship as one of the “wins” of multiculturalism–new immigrants equally aligned to their country of birth and their adopted one–Soutphommasane argues that true patriots need to be citizens of a single country.

In Reclaiming Patriotism, he cites the example of the 2006 bombing of Lebanon, where 25,000 Australians, many dual Lebanese-Australian citizens, awaited evacuation. Commentators at the time expressed concern that some were “bearing Australian passports not out of loyalty but out of convenience”, he writes.

“People are fond of regarding the status of citizenship as conferring only rights but there is a flipside to it too,” he says. The responsibilities of Soutphommasane’s more engaging form of citizenship are “demanding for a citizen to do when they belong to one community alone. When they belong to two, I wonder whether it becomes impossible”.

Soutphommasane himself had the chance to apply for French citizenship at 18, but opted not to. “I like to think I practice what I preach.”

Soutphommasane was born in 1982 in Montpellier, east of Marseilles, in the south of France, the only son of mother Chanthavone and father Thinh. His parents, then medical students, had fled Laos, part of French Indochina, in 1975 following the Communist-Pathet Lao takeover. Although his mother’s first tongue was French and she had relatives in France, his parents, who today both work as registered nurses in the same western Sydney hospital, “never really felt that they could belong to French society”, says Soutphommasane.

The family migrated to Australia in 1985 and within three years were naturalised. The Soutphommasanes, says the son, took their new citizenship very seriously. “I was taught very early that I was an Australian citizen,” says Soutphommasane, who grew up in Canley Vale and later Bonnyrigg Heights and went to a primary school where “90 per cent of students came from Asian-speaking backgrounds”.

The self-admitted perfectionist went on to the selective Hurlstone Agricultural High School–”I was always very bookish…a model immigrant child”,–and it was around this time, as “the only Asian kid at school” that his politicisation became practical.

John Howard’s 1988 statement expressing his concern about the rate of Asian immigration was an early political awakening–”The sting my parents felt from Howard’s comments was all very real,” he writes in Reclaiming Patriotism–and at 15, he joined the Mount Pritchard branch of the ALP.

Soutphommasane went on to study government and international relations on a scholarship at the University of Sydney. At just 21, the high achiever joined former NSW premier Bob Carr’s speechwriting staff. In 2004, he moved to Oxford and in 2006 earned a Masters of Philosophy degree, graduating with distinction, before studying for his doctorate. While there Tim wrote for Leftist news such as The Guardian.

After watching the Cronulla riots unfold with a “sense of shame, a sense of indignation”, Soutphommasane felt compelled to return to Australia to work for change. In 2007, he joined Kevin Rudd’s Prime Ministerial campaign office as a “lowly” research officer.

Sorted !

Sorted !

“For some [Cronulla] amounted to a good excuse to stay away from Australia,” he says. “For me, it really meant that I had to come back and do my part.”

Not content to revel in the left’s fallback position of “indulgent despair”, Soutphommasane is determined to present a “positive vision” for the left and feels optimistic about the future of nationhood on Rudd’s watch.

“He’s embraced the language of nation-building,” says Soutphommasane. “The real challenge now is for him to add a cultural narrative to that language and articulate a vision of citizenship, an agenda for a new social contract.”

“When people think of patriotism, they think of Cronulla, they think of Southern Cross tatts, of Australian flags draped over your shoulder,” he says. “But there is another patriotism out there being lived by many Australians on a day-to-day basis; a multicultural patriotism that is reality in contemporary Australia that hasn’t always been conveyed in public debate.” And that is why he has returned to his country of choice.

“I wanted to come back and be a patriotic agent, for want of a better phrase,” he says. “This is where home is and this is where I want to contribute over the long term.”