One’s great great uncle’s generation of men were the best Australia has produced, thus far.

Subsequent generations of Australians could only imagine; but we mortals should read, learn and must never forget. Mine was blown to bits by the Germans at The Battle of Montbrehain, weeks before the Armistice in 1918.

As a partly-trained stockman on quarter-horses in my lanky youth, I hold personal admiration for Australia’s legendary Light Horse – largely recruited from the land because riding a horse was then a rural necessity and culturally Australian, and Gung-ho bush lads were renowned to be the best horsemen around. And many such Aussie bush lads could shoot a rifle straight and true because it was a necessary tool of the farm from boyhood.

And they were used to hard riding in the hot, dry Australian bush.

Their cavalry of chosen horses were the trusted Aussie bred New South Walers – invariably abbreviated to ‘whalers‘ like everything Aussie. They were the perfect war horse. Read More.

Australia’s Light Horse Regiment were probably the best cavalry at the time.

Before the Great War, Beersheba in southern Palestine was under the Ottoman Empire controlled by the Turks. It was an ancient and rather “squalid” remote desert village serving as primitive camel market for ragheads and camel herders. Biblically, apparently Abraham sank a well there. And the Battle of Beersheba on October 31, 1917, was as much about oasis water as it was about outflanking the Turks in Palestine.

After riding for 30 hours across the desert from near Gaza to this little town 120km south-west of Jerusalem — stopping to fight the enemy on the way — the 800 cavalry British, Australian and New Zealand soldiers and their horses were thirsty with no other options. It was autumn so the heat not as bad as it is in summer.

Matters were looking grim when, after multiple attacks by infantry and mounted troops, the Turkish garrison refused to yield.

Men of the original (1st) Light Horse Regiment at Roseberry Park Camp in New South Wales.

But the Australians, in memory of their countrymen sacrificed two years earlier at the hands of the Turks during the Gallipoli Campaign, were undeterred by old Johnny Turk. By about 3pm, with the “day on the wane”, Australia’s Lieutenant-General Harry Chauvel, who had commanded the 1st Australian Light Horse Brigade on Gallipoli before taking command of 1st Australian Division on 6 November 1915, decided “it was neck or nothing”. He would order a cavalry charge in the fading light.

Chauvel, a proud Australian who at times felt his countrymen were sidelined by their British commanders, had to choose between his last “fresh” units: Brigadier William Grant’s 4th Australian Light Horse Brigade or a British outfit.

But to whom would he entrust the deadly mission? And after hard fighting in the hot and waterless country, the bulk of his large force was spent.

“Put Grant straight at it,” Chauvel said.

Brigadier General William Grant led the charge of the 4th Australian Light Horse Brigade.

(Born 1870 in Stawell, educated Brighton Grammar School, University of Melbourne, had fought in the Gallipoli Campaign against the same enemy. For his duty he received the Order of St Michael and St George and Order of the Nile.

Chauvel chose his kin, Grant, despite the British force being a cavalry unit equipped with swords, while Grant’s brigade was “mounted infantry”; that is, soldiers who rode to a battle then fought on foot.

This is what perplexed the German and Turkish commanders when Grant’s men trotted over the ridge. Usually, the Australians would dismount and fight on the ground. Instead, they charged at full gallop, their sharpened bayonets pointing straight at the terrified Turks.

“The regiments bore neither sword nor lance and, in order to give the charge as much moral effect as possible, the men rode with their bayonets in their hands,” the official historian wrote.

The men all realised “only a wild, desperate throw could seize the prize before darkness closed in and gave safety to the enemy”. Their waler horses were just as wild and desperate. They could smell Beersheba’s water.

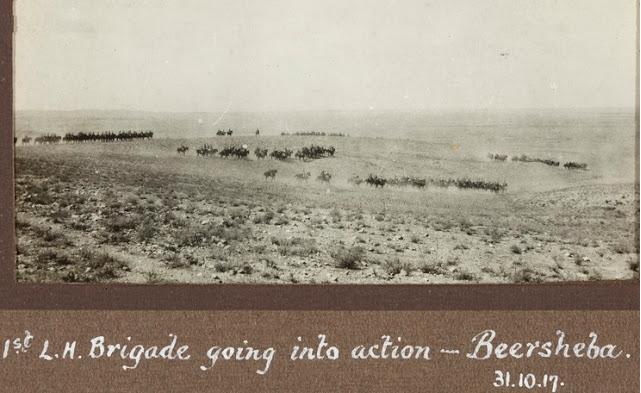

Captain Robert Valentine Fell’s picture of the First Light Horse Brigade “going into action” at Beersheba, October 31, 1917

Captain Robert Valentine Fell’s picture of the First Light Horse Brigade “going into action” at Beersheba, October 31, 1917

Down came the men in a rolling wave of horse and hoof. An irresistible, gathering storm of “stuttering thunder”, said light-horseman — and, later, renowned author — Ion Idriess, who marvelled at his comrades’ grand show.

“We heard shouts among the thundering hoofs … saw balls of flame among those hoofs — horse after horse crashed, but the massed squadrons thundered on,” Idriess wrote.

Turkish machineguns out on the left found the range. Mercifully, the British artillery gunners did the same. The guns barked, knocking out the machinegun nests almost instantly. Accurate and heavy rifle fire punched more holes in the Australian lines. Casualties mounted. The pace quickened. Soon, fewer men fell and then hardly any were being hit. The Turks were firing too high.

With several hundred horsemen galloping straight at them, they had, quite understandably, been panicked into not adjusting the sights on their rifles. The bullets whizzed over the Diggers’ heads and into the ether.

Onward they raced to the two lines of Turkish trenches. Five old Gallipoli hands were shot dead on the very edge of the Turkish line.

The horsemen jumped the first line and made for the second. Some smashed through to the town while others dismounted and went to work on the Turks with their bayonets.

“After between 30 and 40 had been killed with the steel, the rest threw down their rifles and begged for pity,” the official historian wrote.

The “‘Thunder of a light horse charge’ as the cavalry rides towards Beersheba.

Stretcher bearer Albert “Tibby” Cotter — a Test cricketer renowned as one of the fastest bowlers of the era — was collecting a wounded comrade when he was shot dead.

An officer had his horse shot from under him. He calmly dispatched his wounded mount before emptying his revolver into the nearest enemy troops. Not all of them though — he was shot through both legs but survived.

Against some 4000 Turkish defenders, the leading waves of 500 Australians lost 35 killed with 39 wounded. More than 70 horses were also killed. The toll was severe but the shock value of the charge had demoralised the enemy and the attackers prevailed.

“They are not soldiers at all; they are madmen,” a captured German officer said after the battle.

The 4th Light Horse Brigade was a Victorian/NSW force, yet South Australians played a key role in the famous battle. It was a joint ANZAC effort – our 3rd Light Horse Regiment was ordered to attack a heavily defended strongpoint atop a cliff overlooking Beersheba from the east. The New Zealanders converged from the north and east, the Turks fled, chased by Light Horsemen who stopped only to shoot at their routed quarry.

A centenary on, they’re all gone the 800 ANZAC Light Horsemen who stormed across the desert to take Beersheba. Some 1350 Australians and 345 New Zealanders lost their lives in the battle of Beersheba and the Sinai-Palestine campaign.

“Back then our boys wouldn’t have had a clue what they were going to do, it was just a job they had to do. And without any water. I mean those horses were dry for about 48 hours or some bloody thing.” – Australian actor Brian Brown there 100 years later.

Uniquely Australian emu feathers of the Light Horse slouch hat, and only Sandy came home

According to the Australian War Memorial, seven men of the 3rd were killed at Beersheba. They included Lance Corporal Clem Ranford, 19, a clerk from Semaphore. He enlisted at 17 and fought at Gallipoli.

Two months before he died, he wrote about the joy of paddling in the Mediterranean. It was just like “dear old Semaphore in the Christmas holidays”.

Clem’s brother, Sergeant Joseph Ranford, was in the same regiment. He was killed in August, 1916. Clem saw his brother fall, riddled with machinegun bullets.

Also killed at Beersheba was Lieutenant Morton Sandland, 27, a sheep farmer, of Burra South in South Australia. He was a St Peter’s College boarder and was the first Burra man to enlist.

Trooper John Boundey, 27, of Tumby Bay, was shot in the neck and shoulder in December, 1916. In May, 1917, Boundey survived when his horse first fell on him then dragged him several hundred metres by the stirrup. He was killed by a shell at Beersheba.

Trooper John “Herb” Dearman, 23, was a station hand on Eyre Peninsula. Both his feet were blown off by a bomb dropped from a German plane. He died of his wounds that night. His brother, Trooper Will Dearman, “saw him before he was buried”.

Also dead was Trooper Francis “Frank” Kelly, 29, a wool classer and property overseer of Booborowie. Kelly was also the organist at the Booborowie Catholic Church: “He was a universal favourite,” The Advertiser reported three weeks after his death.

Trooper Claude Leahy, 25, a butcher from Naracoorte, served in the South Australian 9th Light Horse Regiment. A bomb dropped by a German airman blew away the back of his head. Trooper Donald Morrison, 26, a labourer from Tantanoola, was killed in the same raid.

When the local priest called to deliver the grave news, Morrison’s wife, Charlotte, refused to believe he was dead. She asked the Reverend David Chapman to write back to say her husband swapped his belt and bandolier with another trooper before he sailed to war, so that man might have been the one killed, not Morrison.

“She very naturally is clinging to the hope that there may be a mistake,” Chapman wrote. There wasn’t. The Red Cross found five witnesses that confirmed Morrison was killed at Beersheba, 100 years ago today.

The subsequent road from Damascus was sweet

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UbYzsexVgZk

Lest We Forget

Lest We Forget