Our ANZAC Day is an annual dedication to our national remembrance of our Australians with New Zealanders past and present who have served, sacrificed, lost their lives in all wars, conflicts, and peacekeeping operations, as well as of the contribution and suffering of all those who have served. Importantly it is to pause to recognise our current serving men and women, particularly those out there now.

Collectively, many Aussies call them ‘Diggers’ – no difference, from ‘The Great War’ (World War I) to the current contingent in Iraq; Aussie men and women.

Anzac Day dates from the landing by the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps soldiers (ANZACs) at Gallipoli at 4:28am April 25, 1915. In their honor, our ANZAC Spirit perpetuates as one of respect, reflection and pride for those who have served in the name of Australia for the freedom we enjoy today. Lest us not forget that.

The Dawn Service is a particularly solemn recognition of this service by any and all Australians and New Zealanders – this is what ‘ANZAC’ stands for.

Back in Australia in February 1918, Australian Army Chaplain, Padre Arthur Ernest White who had served with the 44th Battalion, enlisting in 1916, commemorated the Gallipoli sacrifice by holding a private Requiem Mass for the battle dead at St John’s Anglican Church in Albany, Western Australia.

ANZAC Dawn Service

The first ANZAC dawn service in Australia didn’t take place until April 25, 1930, when at 6am Padre White held a dawn Eucharist commemorating ANZAC Day. Wreaths were laid at the nearby war memorial with some of the congregation who proceeded up a bush track to the top of nearby Mt Clarence. At the summit an observance took place of a boatman laying a wreath in King George’s Sound, where the ANZACs had departed Australia’s shore in 1914 for the War.

ANZACs departing Albany in 1914

ANZACs departing Albany in 1914

Before Gallipoli, some 52,561 Australians and more than 18,000 New Zealanders had enlisted out of dutiful patriotism, some out of an innocent sense of adventure, some to escape boredom or poverty.

ANZACs at Gallipoli suffered 26,111 Australian casualties, including 8,141 deaths; 7447 New Zealand casualties, including 2779 deaths.

Men of the 10th followed two waves of 8th Light Horse, who were annihilated. “Boys, you have 10 minutes to live,” the 10th’s commanding officer said. At the end of the day, 375 of the 600 attackers were casualties.

Historian C.E.W. Bean wrote:

“The West Australians assumed that death was certain, and each in the secret places of his mind debated how he would go to it. Mate, having said goodbye to mate … went forward to meet death instantly, running as straight and swiftly as they could at the Turkish rifles. With that regiment went the flower of the youth of Western Australia …”

Gallipoli was to be an omen of what was to ensue for the Australians on the Western Front.

On 19 July 1916, the 5th Australian Division, together with the British 61st Division were ordered to attack strongly fortified German front line positions near the Aubers Ridge in French Flanders. The infantrymen assaulted over open ground in broad daylight and under direct observation and heavy fire from the German lines. Over 5,500 Australians became casualties. Almost 2,000 of them were killed in action or died of wounds and some 400 were captured. This was the greatest loss by a single division in 24 hours during the entire First World War.

The Battle of Fromelles the most tragic event in Australia’s history.

The Battle of Fromelles the most tragic event in Australia’s history.

Australia’s Sacrifice in ‘The Great War’

- Died before discharge from the AIF: 60,284

- Wounded in action (including gassing and shell shock): 155,133

- Prisoners of war: 4,044

- Suffered from sickness or non-battle injuries: 431,448

(For all official war records go to the official Australian War Memorial website https://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/enlistment/ww1/)

Some 74 Victoria Crosses were awarded to the Australians and New Zealanders “for valour in the face of the enemy“.

Around 420,000 Australians ended up enlisting for service in the First World War, representing 38.7 per cent of the then male population aged between 18 and 44. At the time Australia’s entire population was under 5 million.

By Armistice in 1918, every community in Australia had been decimated from the loss of their menfolk. Towns in the country were conspicuously without men. Many smaller rural Australian communities died.

Nearly every town and community across Australia holds its own ANZAC Day Service for those of the local district – the occasion is that pervasive in the Australian cultural psyche.

ANZAC Day is an important part of Australia’s identity and national spirit, but the national day belongs to the veterans past and present, no-one else. Others can only be bystanders, and their respect to those who have served their nation is due. But the bystanders equally are Australians the families, the descendants, the young, those who turn out just to show their gratitude – for it’s with their participation in ANZAC Day, that all our Diggers with their legacy, retain cultural relevance.

In addition to the Dawn Service, in our nation’s capital Canberra at the Australian War Memorial, remembrance commemoration provides an important nationally televised National Ceremony and, at dusk the Last Post Ceremony. These are hosted by the Australian War Memorial, the Australian Defence Forces in close co-operation with the Returned and Services League of Australia ACT. It is important, not being a big event, but for those who due to disability cannot attend in person.

ANZAC Day March

The first Anzac Day March took place a year after Gallipoli in 1916 along Queen Street, Brisbane. At a time when Brisbane’s population was about 300,000, more than 50,000 turned out gathering the length of Queen Street and outside the GPO.

A press report of the day read:

“The crowds are 10 or 15 deep. Many people are carrying umbrellas. There appears to be more women present than men. The throng is largely topped with hats of all shapes and sizes, tipped this way and that, like a field of variegated flowers.”

First ANZAC Day March in 1916 – Brisbane

First ANZAC Day March in 1916 – Brisbane

Then, the human losses of the war were overwhelmingly raw, the public mood was torn between loyalty and trauma – many were still in shock with raw grief – mothers who had lost sons, children who had lost fathers. It was too early to commemorate the sacrifices by the men because the truth was too close to home and real.

The military had wrongly organised a pageant to invite further enlistment, instead of a solemn march past to honour the dead. It took three generations for ANZAC Day to pass from being a sad reminder of why the seat at family tables was empty. The legend re-emerged just like after three generations, Australians now are proud to have convict heritage, whereas not that long ago such was not spoken about.

We used to know the ANZACs. Now they are history. The remaining dozen or so Australian survivors of World War I will be history soon, too.

The ANZAC Day March in Hamilton, Brisbane, 1937

The ANZAC Day March in Hamilton, Brisbane, 1937

ANZACs, the quintessential Australians

The ANZACs were ordinary Australian men, many then from the land, prepared to put their life on the line for their nation. But what they did in doing that, has become the stories of legends. Humbled by being called ‘heroes’, they were ordinary men who loyally followed orders to bravely run into enemy machine gun fire across exposed open fields and take the chance that some would be lucky and take the enemy, before he took them.

On May 16, 2002, Alec Campbell, the last of our ANZACs passed way at the decent innings of 103. He managed to make it to 2002 because he was only a 16 year old and bored insurance clerk in Launceston when he signed up.

Alec Campbell died peacefully on Australian soil in his home state of Tasmania. He was the last living link to that group of Australian Diggers who had established the Anzac legend. Veterans Affairs Minister Danna Vale said of the ANZACs in 2002, they fought with the kind of courage, integrity and honour that Australia would never forget. “It is a legacy that will live on.”

Alec Campbell was sent off with a State Funeral at St. David’s Anglican Cathedral in Hobart with our Prime Minister at the time in attendance.

Alec Campbell in 2000, was to be the last remaining Gallipoli ANZAC

Alec Campbell in 2000, was to be the last remaining Gallipoli ANZAC

ANZAC Roy Longmore preceded Alec’s passing by a year, aged 101. He had joined up aged 21 while a farm-hand in Geelong, Victoria.

ANZAC Ted Matthews died in his sleep in 1997 managing also to get to age 101. He was a carpenter in Sydney when he joined up at age 17. Matthews was the last to pass who took part in the first ANZAC landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 at what is now known as ANZAC Cove. Early in the landing, Matthews was hit in the chest by a shrapnel shard. A thick pocket-book – a present from his mother – saved his life. After the Battle of Gallipoli, he went on to fight on the Western Front. He was one of the Australian soldiers who were part of remarkable feat of arms achieved at Villers-Bretonneux.

The governor-general, Sir William Deane, called Mr Matthews “the quintessential Australian”. “He was there at Gallipoli, without respite, for the whole duration of the stalemate: through the heat, and the flies, and the stench of death, and disease, and attack, and counter-attack, and the cold as winter drew on. And the bonds which transcended and transcend individual mortality were forged between those men and the soul of our nation.”

Sir William said Mr Matthews’s death marked “a final break in a living thread that united us Australians with the complete Anzac epic”.

Kiwi, Cedric Drysdale Stapylton-Smith, of Christchurch, survived Gallipoli and the Somme and was still smoking and drinking at 104 years.

Contemporary Relevance of ANZAC Day

Australian Regular Army Veteran, John Coyne, served Australia for 14 years, deployed overseas on military operations in Bougainville and East Timor. He is now head of border security at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. It’s his prerogative to write in The Age newspaper April 21, 2015 to raise public awareness of the meaning of ANZAC Day.

We should never forget, never take it for granted – the service, sacrifice of generations of Australians (mainly of our noble young men). Coyne is right. ANZAC Day means many things to different people, but it is a solemn occasion, not a carnival.

Coyne is also right, that after discharge from service, any veteran can choose to do what he or she wants, including on ANZAC Day.

Coyne writes:

“I won’t go to the official dawn service any more. These days I choose to head out into the Australian bush surrounding Canberra. Well before dawn’s first light I make my way to a piece of high ground overlooking a valley floor. I stand too with dawn’s first light, sitting silently and generally shivering in the pre-dawn chill.

To the cacophony of bush noises, I reflect on those who made the ultimate sacrifice while on operations, or after they’d returned home. I think about the cost of our service: both the physical and psychological. I remember our stories, good and bad. After the sun’s rays warm me up I make my way back to my car and return to my family. I have chosen this “dawn service” because I’m not sure there’s a real place for contemporary veterans in Australia’s new-found shared Anzac spirit. This year I think I’m going to bring a couple of mates with me.”

Of course, it’s his prerogative. As a Digger he served and Australians can’t ask for more than that of anyone.

He’s right too. ANZAC Day is a solemn day of respect for the enormous ultimate sacrifice by so many young men in Australia’s name.

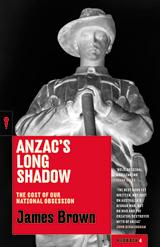

Another of our contemporary veterans, recently retired Captain James Brown of 2 Cavalry Regiment (2CAV) attached to our Australian Regular Army’s 1st Brigade, has penned his insider’s account and scrutiny about the meaning of ANZAC Day. Brown served Australia in Iraq, Afghanistan, and the Solomon Islands.

In his book ‘Anzac’s Long Shadow: The Cost Of Our National Obsession‘, published in 2014, Brown questions our government’s over-emphasis on historic war monuments over what he has witnessed as the contemporary neglect for our current Diggers.

It is his prerogative too.

Brown criticises the extra-ordinary $325 million of taxpayers money that is being spent to commemorate the ANZAC’s history and to festivalise an event that benefits no living Diggers or their families. He criticises Australia’s poor interest in our military, its capability and its personnel, beyond the theatrical parade of calendar public ceremonies, saluting the PC distant past.

He criticises Australia’s simplistic and silo-ed military planning and the woeful Defence budget that seems more about annual materiel quotas than strategic purpose, tactical effectiveness, extensive combat-readiness training, and the properly kitting out and support to our front line troops for battle rigour and survivability.

Perhaps the current Colonel Andrew Lowe is on to it of the Royal Australian Regiment (7RAR) whose about to lead our current contingent of Aussie diggers into fight Islamic State, “If you get into a fight and you shoot straighter and faster than the enemy, you’ll win.”

Brown thinks we need to get better prepared than that.

As an insider, he saw lessons not learned, command cultures with heads in the sand, military mistakes set to be tragically repeated. He foretells our Diggers unnecessarily returning in coffins, with prosthetic limbs, PTSD and indeed with many withdrawing and committing suicide.

Brown calls for major change and it appears many of his peers agree with him. Many point to the enemy within. He extends upon the wise motto of the Vietnam Veterans Association of Australia says it all: “Honour the dead but fight like hell for the living.”

Australian Veteran of Korea, Malaya, Vietnam and Dhofar wars: Keith Payne, VC, AM

Australian Veteran of Korea, Malaya, Vietnam and Dhofar wars: Keith Payne, VC, AM

(NB. We entitle veteran as Veteran, because it deserves to be an honorary title)

The ANZACs never saw themselves as heroes, but would have appreciated the quiet contemplation by future generations of Australians who will pause and remember what they did for Australia. Australia’s famous historian, Manning Clark had said the ANZAC experience was “something too deep for words”. Their ANZAC Spirit arose from so great a sacrifice that it deserves to remain hallowed.

The ANZAC’s were ordinary Australians. They would be embarrassed about all the extravagances and disappointed by celebrations. They would not be angry because they had no room left for anger.

The ANZAC Spirit

The ANZAC Spirit

Lest We Forget