We Observe January 5, The Great Shearers Strike of 1891

The Great Shearers’ Strike of 1891 marked a crude time in early Australia, when ordinary workers were compelled to make a stand against greedy pastoral overlords and their threat of imposing cheap foreign scab labour.

The strike and protests inflamed to becoming a major confrontation between sheep shearers and upstart graziers who pompously regarded themselves as imagined colonial overlords of Central Western Queensland. Troubles brewed around the towns of Winton, Barcaldine, Clermont, Capella, Tambo and Springsure. But it had national repercussions.

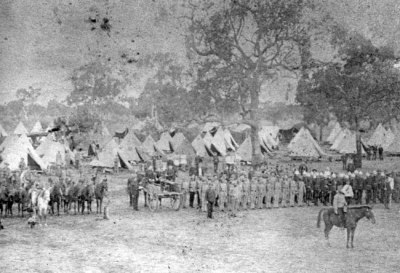

Red Creek Crossing, Winton, Central Western Queensland was the site from January 5, 1891 where striking shearers went on strike for Australian principles, roughing it in tents for 4 long months.

Red Creek Crossing, Winton, Central Western Queensland was the site from January 5, 1891 where striking shearers went on strike for Australian principles, roughing it in tents for 4 long months.

Working conditions for sheep shearers in 19th century rural Australia were Third World atrocious. Their employers – simple sheep graziers were nothing more than government land-granted squatters who couldn’t give a shite about hard-working shearers.

Sheep shearers then only got summer work when the sheep had grown fleece, but for the rest of the year they were forced to be itinerant. Wool was Australia’s Dickensian farm trade that only benefited wool profiteers on the back of Aussie shearers, not the sheep.

In 1891 wool was one of Australia’s largest industries. But as the wool industry grew, so did the number and influence of shearers.

In 1890, a central district council, composed of members of the Queensland Shearers Union and Queensland Labourers’ Union had been formed with their headquarters at Barcaldine. Across colonial Australia, The Australian Shearers’ Union boasted tens of thousands of members, and had unionised thousands of shearing sheds.

The landholding pastoralists or merely “squatters” as was then termed were mainly sheep graziers. They claimed that market prices for their wool were falling. So they decided to cut costs and shearing labour was a main cost. The graziers contrived a ‘Freedom of Contract’ deliberately to undermine and eliminate the union in all shearing. It was euphemistic code for paying lower wages (33% lower) to non-unionised shearers and ringing in low-cost Chinese coolie labour to do the shearing and under Third World conditions. The agreement was a master/servant ‘take it or leave it‘ ultimatum by the graziers and they expected it to take effect from January 1891.

But the shearers wouldn’t have a bar of it and refused to sign it, insisting on their democratic right to work alongside unionists only for a set and fair wage.

Soon after, shearers at Jondaryan Station on the Queensland Darling Downs went on strike in protest.

Now, Jondaryan Station had form. Two generations earlier in 1849, the station owners had refused to pay the shearers for half shorn sheep, so the shearers burnt down the woolshed. In 1874, fifty three Jondaryan shearers there became the first Australian shearers to form a union.

As non-union labour was still able to process the wool, the Jondaryan shearers called for help. The Rockhampton wharfies responded and refused to touch the Jondaryan wool. The unionists won the battle. This galvanised the graziers, and they formed the Pastoralists’ Federal Council, to counter the strength of the unions.

Many union shearers were outraged when Logan Downs Station Manager Charles Fairbain asked the shearers to sign a contract that would reduce the power of their union. On January 5, 1891 the shearers announced a strike until the following demands for a contract were met:

- Continuation of existing rates of pay

- Protection of workers’ rights and privileges

- Just and equitable agreements

- Exclusion of low-cost Chinese labour, which manifested itself later as Labor Party policy – the Immigration Restriction Act, also known as the White Australia Policy.

From January 1891 when the Maritime Union called a black ban on wool shorn by non-union labour until the Rockhampton trial in May of that year, Queensland was on the verge of civil war ‘of more violent proportions than Eureka’.

On 13 January, 1891, a telegram was sent to Barcaldine. It read:

“Private information. Federated pastoralists levying three hundred thousand pounds throughout Australia to fight Queensland…Employers plan to raise thousands blacklegs to take district after district in rotation. Keep this strictly secret. Act cautiously. Big trouble ahead.”

The graziers received the full support of the conservative colonial government who sent more than 1000 armed soldiers and special constables to central Queensland. “Scab” or “blackleg” labourers were provided with military escorts to prevent confrontations with the union shearers.

As the southern free labourers (called ‘scabs’ by the unionists) arrived in Rockhampton on February 10, to be taken by special train to Clermont to service Wolfang, Logan Downs and Gordon Downs, violent confrontations between graziers and union shearers were set to begin.

Barcaldine became the headquarters for the strikers and the site of the biggest strike camp just north of the town at Lagoon Creek. Striking shearers formed armed camps outside of towns.

A meeting of unionists at Barcaldine on 15 February 1891 resolved to fight the agreements and to send all available horsemen to Clermont to assist their comrades. A party of about 180 men, many armed, proceeded to Clermont. The striking shearers at Barcaldine raised the Eureka Flag over their camp in a gesture of defiance of the police and government.

In March more than 3000 striking shearers marched under the Eureka Flag through Barcaldine to protest against poor working conditions and low wages. During rallies they congregated around the Tree of Knowledge at Barcaldine, where a new monument to the striking shearers and the formation of the once proud and true Labor Party stands.

With unionists, soldiers and strike breaking labour pouring into Barcaldine and surrounds the situation was critical. There were about 4500 people in Barcaldine or camped nearby.

The threat of a bloodbath was real, yet the strikers were discipline and no bloodshed.

Thousands of armed soldiers were sent by the Queensland colonial government from Brisbane by train to back the graziers and their ring-in ‘scab labour’ and strike leaders were arrested in Barcaldine and Clermont. The unionist shearers retaliated by raiding shearing sheds, harassing non-union labour and committing arson and sabotage.

A protracted trial of the arrested leaders ended in Rockhampton on May 20 with thirteen of the men sentenced to three years hard labour on St. Helena Island in Moreton Bay. The shearers were unable to hold out. By May the union camps were full of hungry penniless shearers. The strike had been broken. The strike was declared off in Blackall on June 15 and in Hughenden on June 18. The union changed its manifesto by encouraging unionists to enrol on the electoral roll to have their voice heard.

The squatters had this time got order through Queensland military, but accepted that the might and following of the Shearers’ Union could not be railroaded.

1895 shearing at Jimbour Station, 70km NW of Jondaryan on the other side of Dalby, Darling Downs, Queensland – note: Australian unionised shearers on decent wages. No cheap Chinese in the sheds, just in the paddocks.

1895 shearing at Jimbour Station, 70km NW of Jondaryan on the other side of Dalby, Darling Downs, Queensland – note: Australian unionised shearers on decent wages. No cheap Chinese in the sheds, just in the paddocks.

But it was all on again three years later in 1894. Striking shearer Samuel ‘Frenchy’ Hoffmeister is shot and killed at a billabong along Four Mile Creek near Kynuna, about 160km northwest of Winton in western Queensland. Banjo Paterson, an Australian legendary poet writes about him in ‘Waltzing Matilda‘. It was on again in 1896, then in 1926, in 1956 and during the Wide Comb Dispute in 1983, when graziers thought they could again ring-in scab labour from New Zealand to avoid paying Australian unionised shearers their fair and decent wages.

Another Australian legendary poet, Henry Lawson, wrote ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’ in 1891 around the time of the first strike, to support the freedom rights of the Australian shearers to rebel against the graziers’ master/servant attitude of exploitation:

Freedom on the Wallaby

“Australia’s a big country

An’ Freedom’s humping bluey,

An’ Freedom’s on the wallaby

Oh! don’t you hear ‘er cooey?

She’s just begun to boomerang,

She’ll knock the tyrants silly,

She’s goin’ to light another fire

And boil another billy.

“Our fathers toiled for bitter bread

While loafers thrived beside ’em,

But food to eat and clothes to wear,

Their native land denied ’em.

An’ so they left their native land

In spite of their devotion,

An’ so they came, or if they stole,

Were sent across the ocean.

“Then Freedom couldn’t stand the glare

O’ Royalty’s regalia,

She left the loafers where they were,

An’ came out to Australia.

But now across the mighty main

The chains have come ter bind her –

She little thought to see again

The wrongs she left behind her.

“Our parents toil’d to make a home

Hard grubbin ’twas an’ clearin’

They wasn’t crowded much with lords

When they was pioneering.

But now that we have made the land

A garden full of promise,

Old Greed must crook ‘is dirty hand

And come ter take it from us.

So we must fly a rebel flag,

As others did before us,

And we must sing a rebel song

And join in rebel chorus.

We’ll make the tyrants feel the sting

O’ those that they would throttle;

They needn’t say the fault is ours

If blood should stain the wattle!”