That Australia is the lucky country is not accidental. ‘The heroes of our nationhood were not resistance leaders or freedom fighters, but politicians and statesmen, most now forgotten or only half-remembered. Their creation is an achievement worth celebrating

An amazing, but little remarked, fact in the current concern about securing Australia’s borders – cue ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ – is that they are entirely maritime. We have no land borders, and Australia is the largest country in the world not to have any – a coastline of 60,000 km plus a stack of islands, the Southern Ocean and Antarctica. The perimeter of our territorial waters is probably longer, and the outer edge of our exclusive economic zone longer again.

Back on shore we have, of course, state borders, and we once built a rabbit-proof fence over thousands of kilometres of outback (largely infertile – so foreigners don’t get any ideas). Only at sea do we share international borders with other countries – Papua, Indonesia and East Timor.

Australia is the only inhabited continent that is not criss-crossed with international boundaries and a patchwork of nation states. Not for us razor-wire fences, concrete barriers, guard-posts, check-points, manned border-crossings, heavily armed border patrols, disputed terrain. We are one country, one nation, spanning an entire continent and its offshore islands. The shape is so iconic, so much the image of our country, that we take it for granted.

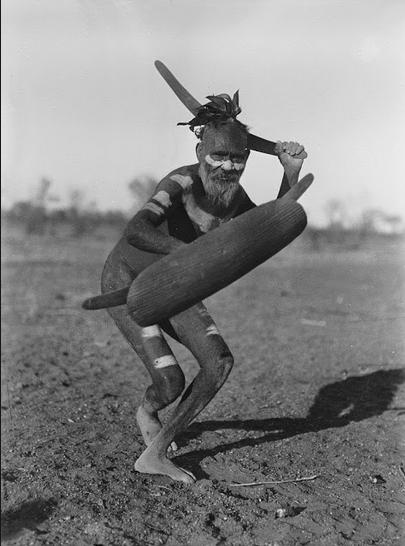

It is pertinent to ask how this happy situation came about. It was not, it must be said, anything to do with the first inhabitants, the Aborigines and Torres Strait islanders. Whilst they had spread across the entire continent and adjacent islands, and shared a nomadic hunter-gatherer existence, they were divided into around 250 separate tribal groups, each with its own traditions, customs, language and territory, with which it had a strong and deep affinity.

Whilst there was, of course, contact between adjacent groups, it is doubtful whether there was any knowledge of, or affinity with, groups beyond this range of contacts, with those living on the other side of the continent. Nor is it likely that the first inhabitants had any concept of the country, of the continent, of Australia, in its entirety.

This awareness could only come in the modern era.

“I want to celebrate Australia because we’ve got a great country here.”

-Warren Mundine January 26 2018

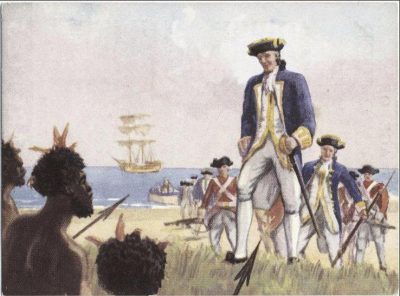

So it was the British, at the end of the eighteenth century, who changed all that. It was an Englishman, Arthur Phillip, who with a small ceremony on the shore of Botany Bay on 26 January, 1788, began the annexation of the continent for the British Crown.

Captain Arthur Phillip – Australia’s George Washington

Captain Arthur Phillip – Australia’s George Washington

It was another Englishman, Matthew Flinders, who first circumnavigated the continent and revealed in detail its size and shape, and it was he who bestowed upon it the name ‘Australia’.

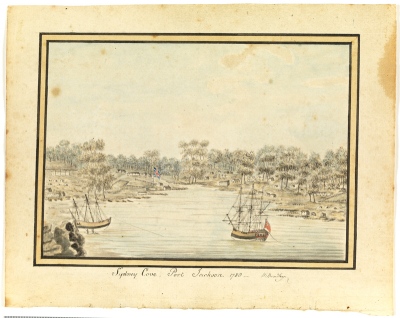

In just a mere 113 years after Arthur Phillip established the first British settlement at Sydney Cove, Australia became a united sovereign nation, taking its own place in the world. This it achieved freely, and with the encouragement and consent of Britain. There was no ‘throwing off of the British yolk’, no need for an independence struggle. The heroes of Australia’s nationhood were not resistance leaders or freedom fighters, but politicians and statesmen, most now forgotten or only half-remembered.

Sydney Cove at Port Jackson 1788 – painting by William Bradley

Sydney Cove at Port Jackson 1788 – painting by William Bradley

From the moment of Phillip’s annexation Australia became part of the British Empire, and through this the Anglosphere, that group of English-speaking countries that subscribe to the same values and share the same heritage of democratic institutions, parliamentary system of government, separation of church and state, equality before the law, respect for private property, strong civil society, protection of basic freedoms. It has been upon this base that Australians, old and new, have built our remarkably prosperous, free, open, tolerant, outward-looking, progressive and enterprising way of life. It is this bedrock, not the continent’s great wealth of natural resources, that makes Australia a ‘lucky country’.

And the Aborigines don’t realise how lucky they were. It could have been the French or Dutch, or the bloody Japs!

Discovery and annexation of the then Third World terra nullius was inevitable. On no other continent have the original inhabitants been successful in holding on to their lands and traditional ways of life. Through waves of discovery, conquest, migration, settlement, by people ever more technologically and organisationally advanced (i.e. First World), similarly subsistence hunter-gatherers either adapted, or were forced into ever more remote, inaccessible and inhospitable terrain, as in Asia, Africa and the Americas, or driven to extinction, as in Europe and the Middle-East.

What is remarkable in the case of Australia is that it hadn’t happened earlier, and that the first inhabitants were able to enjoy their so-called ‘idyll’ for as long as they did – 60,000 years. (Some idyllic lifestyle – it was internecine, uncivilised, disparate and chaotic).

So it if hadn’t been the British, it would have been someone else, or a bunch of others, contesting the terrain, carving it up, claiming it as their own. Given the location of ‘the Great South Land’, there was, however, only a shortlist of likely contenders, with the requisite technological and organisational capacity, the global reach and the territorial ambitions, to accomplish the feat, either on a full-scale or piecemeal basis.

No-one else in the region, the Papuans, the Javanese, the Japanese or the Chinese, for example, felt so inclined or had the logistics to invade the place. Otherwise, presumably, they would have done so ages before. Arab traders, who for centuries had conducted business as far east as the spice islands to our north, and who brought their religion with them, apparently never reached these shores or contemplated coming here.

Even the Moluccans, who for a long time had fished and traded along the northern coast, failed to establish any permanent settlements on the Australian mainland.

By the modern era, therefore, it was most likely that it would be a European maritime power that would do it and, of those, there were only four other real contenders – the Portuguese, the Spanish, the Dutch and the French.

As it happened, it was the British. It was they who brought the country into the global community.

But we could pause, perhaps, to contemplate had it been otherwise. The Portuguese and the Spanish, of course, had been around Australian waters for hundreds of years before 1788, but did not take the extra step of planting settlements in Australia. Had they done so, then the country certainly would have been different, and perhaps more akin to Latin America today. The Spanish and the Portuguese had a record for being less enlightened and more despotic colonisers than the British ever were, and their legacy in the lands they did conquer has not been as stable, democratic or economically as successful.

The Dutch were in the East Indies, also, for centuries before, without seriously contemplating colonising the great land to the south. They had their chance. Had they done so, then perhaps Australian settlement would have been much more like that of the Afrikaaners in South Africa, where they did put down roots, with all that would have entailed, particularly for the original inhabitants. There wouldn’t be any Aborigines left.

The French, like the British, were much later on the scene, and had La Perouse not been pipped at the post by Phillip’s First Fleet, then New South Wales, or whatever other name it would have had, could possibly have become French territory. And lookhow the French have treated Africans in all their colonies there!

Many Anglophobes and Francophiles, of course, would perhaps think that would have been a better outcome, but one thing is certain, Australia today would be much more French than it is recognisably British. The French, of course, have had a different attitude to de-colonization to that of the British. They, the French, have been most reluctant to give up any of their colonies, and in those in which the locals have not been able to force them out, they remain to this day, as they do in nearby New Caledonia and French Polynesia.

Contemporary Australia is clearly no longer outwardly British, (despite some republican assertions to the contrary). Indeed, it hasn’t been so for some time, and it is difficult to say when it was the British actually left. That would not be the case, I venture, with the French, had the country started out as a colony of France.

The other possibility, already mentioned, is that the continent of Australia could easily have been not a single nation, but one divided into competing European colonies, with all the likelihood of frontier disputes and inter-colonial wars. Australia was spared this because British claims to the whole continent were never successfully challenged by either the inhabitants or by other European or regional powers. Not having to share a land border with another nation has bestowed upon us huge benefits, especially in the areas of defence, quarantine, customs, immigration and in terrorism prevention. Australia is its own customs union, free-trade area and common currency block. It has only one official language and a unified legal system. If we think that protecting a sea border is a difficult enough exercise, and that the interstate rivalries and constitutional wrangles that bedevil the federation are often tedious and troublesome, we should spare a thought for what it may have been like had Australia been not one country but many.

So, all in all, the country could have done worse than have Arthur Phillip plant the Union Jack on its soil (230 years ago).

Although they didn’t appreciate it at the time, Phillip probably gave the first inhabitants as good a chance of surviving in, and adapting to, the global world as any ‘invader’ could have given them, and the waves of immigrants that subsequently came, and are still coming, to these shores, a much freer, safer, fairer, equitable, open, tolerant and prosperous place in which to start a new life than might otherwise have been the case.

(Compare this to how the French, Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish and Germans treated their discovered Third World subsistence primitives).

January 26, 1788, is well worth commemorating, and celebrating, as Australia’s Day.’

Source: January 26th 2017 , by Leo Maglen, ‘Why Australia Day Matters’, Quadrant Online, https://quadrant.org.au/opinion/qed/2018/01/australia-day-matters/

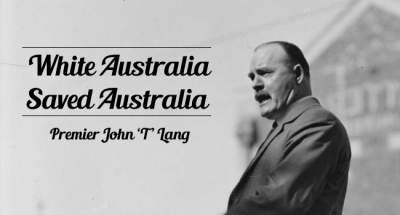

White Australia SAVED Australia

Jack Lang was the Premier of New South Wales during 1925-1927 and 1930-1932. In this extract from his book, I Remember, Lang gives a brief history of the White Australia Policy; exposes how Britain interfered with local attempts to keep the hordes of coloured immigrants from flooding into our country; and praises the policies that established White Australia.

White Australia must not be regarded as a mere political shibboleth. It w as Australia’s Magna Carta. Without that policy, this country would have been lost long ere this. It would have been engulfed in an Asian tidal wave. There would have been no need for the Japanese to invade this country. We would have been swallowed up by the rolling advance of a horde of colored people, anxious to escape the privations of their own countries and prepared to impose their own standards on this country.

It is necessary only to examine the racial composition of present-day Fiji, where the Hindus have elbowed the natives out of the picture, to visualise what could have happened in this country had the White Australia policy not been fought for doggedly at the end of the l9th Century. We were then fighting for our national survival. Had we weakened, the flood gates would have opened and the natural increase of population according to Asian standards would have done the rest. It would then have been too late. This country would have become a pushover for the Asiatics.

The first Federal Platform for the Labor Party, adopted at an Interstate Conference held in Sydney on January 24, 1900, was a model of brevity. It was the platform on which the party fought its first Federal election in the following year. There were only three planks. They were (1) Electoral Reform, providing for one adult one vote. (2) Total Exclusion of colored and other undesirable races, and (3) Old Age Pensions.

The Conference also agreed that the Constitution should contain machinery for the Initiative and Referendum to alter the constitution, and that instead of double dissolutions there should be a National Referendum to settle deadlocks between the two Houses.

But it was the question of White Australia that knit the first Federal Labor Party together. In 1908 when the party decided to draft a much more elaborate platform, the first plank agreed upon was “Maintenance of White Australia.” It headed the list.

So the Australian Labor Party was actually brought together with White Australia as its primary objective. Later the word-spinners put it much more elegantly as “The cultivation of an Australian sentiment, based on the maintenance of racial purity.”

That was not, however, the real reason for the development of the White Australia policy. It did not have its origin in any idea of racial superiority, or color prejudice. From the start it was a simple bread-and-butter issue. Australian workers were trying to defend their own living standards. They were trying to save their jobs. They knew that unrestricted immigration of colored races would mean the introduction of a kind of industrial Gresham’s Law – the bad wages would put the fair wage out of circulation. The white Australian worker would soon be reduced to coolie levels. Having got rid of convict labor, they did not want to be reduced to the rice bowl. Yet that was the threat that was actually hovering over the people of this country.

The man to whom we owe a great deal for saving Australia was Henry Parkes. He was not only a dogged believer in White Australia, but he also had the practical political brain capable of devising ways and means of overcoming the problem.

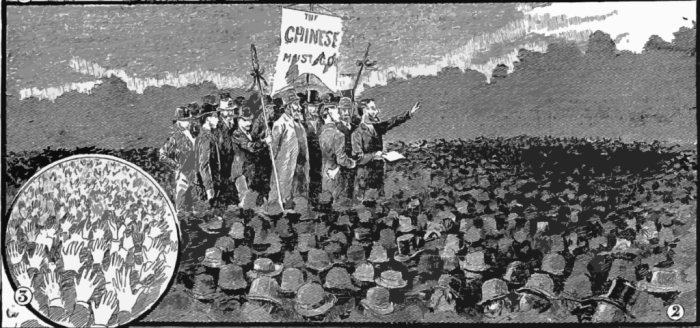

Trouble first started during the Gold Rush. It didn’t take long for news of the strike to reach the gold merchants of Shanghai and Hong Kong. Chinese had flocked to the Californian fields in 1849, so that even today San Francisco has the largest Chinese settlement outside Asia. Then as the Californians pulled up their grub stakes and followed the trail to the new strikes in the Southern Hemisphere, the Chinese followed on.

They were the fossickers of the goldfields.

Trouble broke out between the Diggers and the Chinese on the Lambing Flat fields in July, 1861. The tough diggers attacked the Chinese and used strong-arm methods. There were all kinds of wild threats. The Government ordered troops into the fields, including artillery, and in the riots that followed one digger was killed. The miners then decided to take an interest in politics, with the elimination of the Chinese as their first objective. Lambing Flat is in fact just as significant in the history of the Labor Party in this State as Eureka Stockade was in Victoria.

Some of the mining companies had discovered that the Chinese were prepared to work longer hours for much lower wages than Australians. That was the chief reason why they were resented. Trouble spread tothe shipping companies, and there were strikes brought about by the employment of Chinese on Australian ships.

Chinese were also coming into Australian ports, deserting and starting their own businesses. Parkes saw what was happening in Sydney. He announced that he was against further Chinese immigration. He was attacked by wealthy employers and accused of having a bias against the Chinese because they were colored. They said he was treating them as an inferior race. Parkes retorted:

“They are not an inferior race. They are a superior set of people. A nation of an old, deep-rooted civilisation. It is because I believe the Chinese to be a powerful race, capable of taking a great hold upon this country, and because I want to preserve the type of my own nation, I am and always have been opposed to the influx of Chinese.”

The Cowper Government was the first to introduce a poll-tax on Chinese. After Lambing Flat it introduced a Chinese Immigration and Restriction Act which permitted the entry of only one Chinese to every 10 tons’ burden of ship, with a poll-tax of £10 on every Chinese permitted to enter, and an annual payment of £4 for every year he remained in the State. Parkes further tightened the Act, and made the poll-tax apply not only to those coming in by sea, but also to those entering from another State.

In 1888 Parkes imposed even more drastic restrictions. He limited the number to one Chinese passenger to every 300 tons, increased the poll-tax to £100, refused them naturalisation and stipulated that they could not work in the mining industry without a permit from the Minister for Mines.

The fight had only just started. It was one thing imposing a poll-tax, but it was another policing it. One Chinese looked very much like another. Many slipped in without paying the head-tax. Gradually, they started to congregate in Chinese quarters in the city and take up their own occupations. Merchants indentured labor from Canton, and had the Chinese tied up with labor contracts that made them little better than slaves.

Furniture-making became one of the chief occupations. They were excellent cabinet makers. But instead of an eight-hour day, they were working twelve and fourteen hours, seven days a week. One of the principal parts of the city in which they congregated was the notorious Wexford Street, behind Mark Foys. It was a narrow, squalid street with lanes running off it, running from Elizabeth Street to Liverpool Street. It was later resumed for the building of Wentworth Avenue. But not before it had many crimes to its discredit, and a bubonic plague scare as well.

The Chinese also had another settlement out in Waterloo, while they had market gardens in Botany. In the city they had their own joss houses, their own restaurants, and their own stalls in Paddy’s Markets. The itinerant Chinese vendor with his bamboo over his shoulder, carrying large vegetable baskets at each end, or selling feather dusters from door to door was a feature of inner city life. Personally most of the vendors were popular, and honest to a fault. But the trade unions realised that if the Chinese could get away with long hours and low pay they would not be in the race to get better conditions.

Urged on by the Labor Party, George Reid, in 1897, had a Bill for the Exclusion of Inferior Races passed through both Houses. When it reached the Governor, he decided to reserve it for Royal Assent. It was forwarded to Downing Street, and the British Government ruled that it would infringe on Britain’s trading treaties with China, and might even endanger the holding of Hong Kong. So on the advice of her Government, Queen Victoria refused her Royal Assent. Reid returned to the attack, and passed another Bill which authorised the N.S.W. Immigration authorities to apply a dictation test to any intending immigrant, if they so decided. That was the origin of the Dictation Test device, which was later incorporated into the Commonwealth Immigration Act of 1901 and is still there. It has given the lawyers many rich briefs and has had some strange interpretations – even to the extent of being applied to British subjects with the approval of the High Court.

But in 1898 Reid only wanted to keep out the Chinese. There was no real trouble about other colored races. There were a few Hindus outback. There were Afghan hawkers with their camels along the Darling.

In Queensland they had the Kanaka problem with the sugar cane industry. The sugar mills said they couldn’t compete with sugar grown with colored labor in the West Indies, or even Fiji. So they recruited island labor from the South Seas, who were called “Kanakas.” Polynesians were indentured for five years at nominal wages. That led to the black-birding of labor in the islands by bullying captains. The Queensland Labor Party under Dawson and Fisher led the fight against Black Australia. Sir Samuel Griffiths, later Chief Justice, took up the cause and agreed to legislate to prohibit the importation of Kanakas from the islands. He won the elections and passed the Act. Then the sugar combine got to work. They told him that he would ruin the sugar industry. Griffiths then repudiated his election pledge, on which he had beaten McIlwraith and brought in a number of regulations regarding how the blacks should be employed. Labor kept up the fight in Queensland and eventually won, after agreeing to the proposition that the sugar industry should be subsidised by a bounty to keep it white. That was not until after Federation.

Meanwhile, Labor in New South Wales still had to win its fight. In the very first Labor League Conference in 1891 a motion was carried, and placed on the party’s platform providing that all furniture made by Chinese labor should be stamped. It was generally believed that much of the work was shoddy.

Later, conference after conference dealt with the problem. The Furnishing Trade Union led the fight. They contended that white labor could not compete with colored labor because of the hours and conditions.

The Labor Party platform adopted by the 1909 Conference passed a resolution that the following should be placed on the fighting platform to be implemented by the first Labor Government to be elected:

(a) “All Chinese furniture factories to be restricted to 48 hours per week, and that the 48 hours be worked between 7.30 a.m. and 6 p.m., Mondays to Fridays inclusive, and between 7.30 a.m. and 1 p.m. on Saturdays, and that overtime can only be worked after obtaining the sanction of the Department of Labor and Industry.”

(b) “All Chinese furniture and other manufactures be so stamped.”

That went on to the platform and remained there many years. The McGowen Government did nothing. The Holman Government had too many other matters on its mind, and during the First World War, the trade unions were not so active in their demands. Then John Storey again shelved the Trades Hall requests for action.

It was not until my Government passed the necessary legislation in 1926 that such furniture had to be properly stamped.

It had been almost impossible to police the Factories Act, while the Chinese could be used in back yards and back rooms. The finished goods were sold through wholesalers, and the retailers had no way of telling whether they were made by Chinese or white labor. But the stamping provisions ended all such doubts. The name of the manufacturer had to be clearly shown, and the industrial inspectors did the rest. The union also adopted an O.K. card, so that it was able to police the workers inside the industry, and inspect conditions.

It meant that Chinese employed in the industry had to get the same wages and conditions as other unionists. It ended the unfair competition. It also ended the shoddy furniture business. The union had the right to see that furniture was true to label, and institute prosecutions if any misrepresentation was being made. With all these precautions, it was not long before the threat of colored labor had disappeared from the industry. Trade union action finished the job started by the legislators.

Those who advocate admission of colored labor quotas invariably ignore the economic reasons responsible for the White Australia policy. While they had their origin in the anxiety of Australian workers to maintain their standards of living, the White Australia policy has more than justified itself on national security grounds. If this country had admitted Japanese even to the same degree that Honolulu admitted Japanese, what would our position have been in 1942? Would it be safe to admit unlimited numbers of Indonesians, Hindus or Chinese today?

Even the United States has had to wrestle with the problems of Jim Crowism, racial segregation and color discrimination. Labor didn’t want this country to have similar problems. Had we listened to the do-gooders and the crusaders for international brotherhood and racial equality, the barriers would have come down long ago. Our living standard would have been destroyed. We would have had intermarriages of races, half-castes and quarter-castes with all the social dilemmas that invariably follow such racial mixtures. We would have had a Black, Brown and Brindle streak right through every strata of our society. Instead we risked the charge that we were drawing the color line. We decided to keep this country as a citadel of the white peoples. Australia is still White Australia thanks to those who battled against those who wanted to exploit colored labor for their own ends.

We must keep it that way.’

Source: January 24, 2018, by Grant in Founders, History , Nativist Herald, http://nativistherald.com.au/2018/01/24/white-australia-saved-australia/

Australia Day celebrations to be extended to an annual Australian Victory Week!

Oz – a Brief Timeline

Before 1770: Australia didn’t exist as a nation. The continent was legally terra nullius in which hundreds of disparate primitiev trives of Aborigines roamed the land, hunter-gathering and fighting amongst each other – it was uncivilised chaos.

From the thirteenth century into the First World Enlightenment era, various First World nations (Britain, Holland, Portugal, France, Spain) explored the Third World and became interested in opportunities from Asia about this land to the south. From the sixteenth century European cartographers and navigators gave the continent various names. The Dutch called it New Holland – the greedy bastards – they’d already got the East Indies (now Indonesia). The Brits call it Terra Australis Incognita or “unknown southern land”.

Between 1606 and 1770 more than 50 European ships made landfall on Australian soil, but it was mainly the Western Australian desert which didn’t look inviting. So the British are on to it. King George III commissions Lieutenant James Cook to go exploring for new British frontiers across the unknown ‘new world’ (Third World).

1770: Cook heads off and discovers various lands needing civilising. He’s the first First Worlder to discover the coast of Terra Australis Incognita which looks a whole lot better than WA. Cook proclaims it no longer incognita and settles just on ‘Terra Australis‘ – the first of many Aussie abbreviations. Eventually we would abbreviate it again to just ‘Australia’ or ‘Oz’.

He raises the Union Jack on what is now called Possession Island on 22 August 1770 to claim the eastern half of the continent as New South Wales for Great Britain.

“Hey cobber, consider yourselves about to be civilised, you can have the day off.”

So Britain got first dibs downunder and it was on to include this Great Southern Land as part of Britains first world civilisation. The scattered anarchist Abos had had 60,000 years head start, but had done squat. So tough titties!

1776: Americans with their Revolution against the British and so London decides its criminal overcrowding problem can be solved by utilising Terra Australis – before the French and Dutch get any ideas.

1788: Captain Arthur Phillip, commander of the First Fleet of eleven convict ships from Great Britain, and the first Governor of New South Wales, arrived at Sydney Cove on 26 January and raised the Union Jack to signal the beginning of the colony.

1804: Early almanacs and calendars and the Sydney Gazette began referring to 26 January as First Landing Day or Foundation Day. In Sydney, celebratory drinking, and later anniversary dinners became customary, especially among emancipists.

1818: Governor Macquarie acknowledged the day officially as a public holiday on the thirtieth anniversary. The previous year he accepted the recommendation of Captain Matthew Flinders, circumnavigator of the continent, that it be called Australia.

1838: Proclamation of an annual public holiday for 26 January marked the Jubilee of the British occupation of New South Wales. This was the second year of the anniversary’s celebratory Sydney Regatta.

1871: The Australian Natives’ Association, formed as a friendly society to provide medical, sickness and funeral benefits to the native-born of European descent, became a keen advocate from the 1880s of federation of the Australian colonies within the British Empire, and of a national holiday on 26 January.

1888: Representatives from Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and New Zealand joined NSW leaders in Sydney to celebrate the Centenary. What had begun as a NSW anniversary was becoming an Australian one. The day was known as Anniversary or Foundation Day.

1901: The Australian colonies federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia. The Union Jack continued as the national flag, taking precedence over the Australian red and blue shipping ensigns gazetted in 1903. Melbourne was the interim federal capital. The Australian Capital Territory was created out of New South Wales in 1908, the federal capital named Canberra in 1913, and the Parliament House opened there in 1927.

On 23 December 1901, the Immigration Restriction Act came into law. It had been among the first pieces of legislation introduced to the newly formed federal parliament. The legislation was specifically designed to limit non-British migration to Australia and allowed for the deportation of ‘undesirable’ people who had settled in any Australian colony prior to federation. It represented the formal establishment of the ‘White Australia policy’. Too right! Keep the shitholers out!

1930: The Australian Natives’ Association in Victoria began a campaign to have 26 January celebrated throughout Australia as Australia Day on a Monday, making a long weekend. The Victorian government agreed with the proposal in 1931, the other states and territories following by 1935.

1938: Having won the Fronier Wars against various Aboriginal tribes, by 1934 state premiers celebrated the Sesquicentenary together in Sydney. The vanquished licked their wounds and started frothing about getting compo – White Welfare and citizen rights.

1946: The Australian Natives’ Association prompted the formation in Melbourne of an Australia Day Celebrations Committee (later known as the Australia Day Council) to educate the public about the significance of Australia Day. Similar bodies emerged in the other states, which in rotation, acted as the Federal Australia Day Council.

1948: The Nationality and Citizenship Act created a symbolic Australian citizenship. Australians remained British subjects.

1954: The Australian blue ensign was designated the Australian national flag and given precedence over the Union Jack. The Australian red ensign was retained as the commercial shipping ensign.

1979: The Commonwealth government established a National Australia Day Committee in Canberra to make future celebrations ‘truly national and Australia-wide’. It took over the coordinating role of the Federal Australia Day Council. In 1984 it became the National Australia Day Council, based in Sydney, with a stronger emphasis on sponsorship. Incorporation as a public company followed in 1990.

1984: Australians ceased to be British subjects and PM Bob Hawke (a communist) undemocratically replace Waltzing Matilda with PC Advance Australia Fair as our national anthem. What a bum!

1988: Sydney continued to be the centre of Australia Day spectacle and ceremony. The states and territories agreed to celebrate Australia Day in 1988 on 26 January, whereas innovative Aussies use up their leave to perpetuate the long weekend tradition.

1994: Celebrating Australia Day on 26 January becomes an established and significant day in the national calendar with almost all Aussies respecting it as ‘more than a day off’ but a deserved long weekend.

2018: January 28 and thanks to the recognition by a few traditional minded Aussie lads in Kalgoorlie enjoying backyard barbie to celebrate the anniversary of Kalgoorlie Digger Uprising of 1934, Australia First Party proposes that Australia Day be extended beyond the long weekend to an Australian Victory Week!

“Stay white Australia, Happy Victory Day”.

“Stay white Australia, Happy Victory Day”.

Thanks Kalgoorlie!

A big country deserves a big party. And bugger any anti-Australian sentiment – deny the golly frothing leftards White Welfare and so problem sorted.

Source: The Australia Day Timeline, by historian Dr Elizabeth Kwan, https://www.australiaday.org.au/about-australia-day/history/