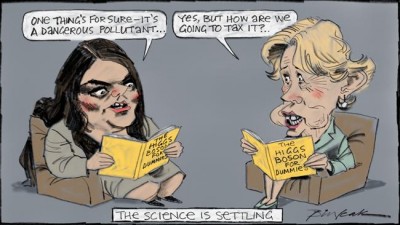

The following editorials have appeared in The Australian in the past few days. They reflect on the end of the Greens Carbon Tax that did nothing but harm.

“One party more than any other in this country is accountable for the new do-nothing status quo on climate change, and that is the Australian Greens.

It is one of the great ironies of modern politics.

This nation no longer has a policy to address climate change: not a carbon tax, not an emissions trading scheme, not “direct action”. For some, that’s undoubtedly a good thing, but the polls tell us that for the majority of Australians, it is disappointing.

Labor wants an ETS, the Coalition wants direct action, the Greens want a carbon tax. But the parties can’t come together on any one approach.

There was a moment in time during Kevin Rudd’s prime ministership when legislation for action on climate change could have been passed, without the prospect of it being repealed, as occurred on Thursday when Tony Abbott fulfilled his election pledge to do away with the carbon tax. That moment was in Rudd’s first term, when his ETS was opposed by the Greens as well as the Coalition.

Had the Greens supported the ETS Rudd took to the 2007 election (essentially the same scheme John Howard took to that election), it is hard to see how it ever would have been repealed.

There may have been debates after the failure of the Copenhagen conference about reducing the trading price or even marking it right down to zero until a global trading scheme took effect, as Clive Palmer is now suggesting. But total abolition was politically out of the question and probably would have remained that way.

Remember, under Malcolm Turnbull’s leadership it was the Liberals who were most divided on this issue. The likes of Environment Minister Greg Hunt, praised by the PM on Thursday for his hard work in repealing the carbon tax, were passionate advocates for an ETS. Other senior ministers who now line up in support of the repeal but previously argued for an ETS include Julie Bishop, George Brandis, Christopher Pyne and Ian Macfarlane. Abbott himself wrote an opinion piece in this newspaper imploring his colleagues to get behind Turnbull and pass the ETS.

Never forget that at the time it was the upper echelons of Turnbull’s shadow cabinet who believed supporting an ETS was not only good policy, but the only way that the Coalition could avoid being politically tarred and feathered. Those who fought against this (ultimately incorrect) consensus at the time included Mathias Cormann, Cory Bernardi, Brett Mason, Nick Minchin, Eric Abetz, Kevin Andrews and Mitch Fifield. History demands that they receive due credit. Some agitated publicly from the backbench, others argued internally on the frontbench. History has vindicated them, at least when it comes to the politics of climate change. But the conservatives winning the day on the ETS is a moment in time that never would have arrived had the Greens heeded Voltaire’s words in his ethical poem La Begueule, which, loosely translated, suggests that the perfect is the enemy of the good.

Trees smeez! Me illegal luvlies mean more to me than me own kids!

Trees smeez! Me illegal luvlies mean more to me than me own kids!

For most environmentalists, certainly for most climate-change advocates, Rudd’s ETS was good. At the very least it was the lesser evil compared with the situation Australia now finds itself in.

It may not have been perfect, but it would have firmly put in place a plan for national action on climate change.

In 2009 that wasn’t good enough for the Greens. They sensed a mood for more than that in the community. They believed that the country was ready for more dramatic action. It is hard to know if the Greens simply miscalculated the changing landscape of climate change politics in Australia, or if their opposition to Rudd’s ETS was based on policy purity mixed in with political self- interest. A desire to break into the lower house may have played a role in the Greens thwarting Rudd’s ETS, with all the long-term consequences doing so has had.

Lindsay Tanner was under pressure in his seat of Melbourne. He had come close to losing the seat to the Greens a number of times, but with Labor in office the minor party had a unique opportunity to stick to policy purity for the sake of political advantage. It clubbed Labor hard in the seat of Melbourne for a weak ETS policy during mid-term campaigning ahead of the 2010 election.

When Labor expelled Rudd from the leadership and went to the 2010 election advocating only a people’s assembly to determine climate-change policy, the Greens picked up the seat.

It is unlikely Abbott would have become Liberal leader had the Greens supported Rudd’s ETS in the first half of 2009 — certainly not in the short term.

Joe Hockey, who blew himself up during the internal party debate over the ETS in late 2009 when he suggested a conscience vote, more than likely would have taken over from Turnbull if a leadership change eventuated only after an ETS had already been legislated by Labor and the Greens.

Besides, it was only after Rudd baulked at fighting a double dissolution election on an ETS that his popularity and the standing of his government plummeted. That would have been less likely — and certainly less pronounced — had the Greens supported the ETS into law in 2009. And don’t forget it was the Greens who insisted Julia Gillard’s post-2010 policy be called a carbon tax, ensuring its political failure given Gillard’s pre-election promise that “there will be no carbon tax under a government I lead”.

Despite politically damaging debates seeing a litany of leaders who advocated action on climate change being cut down, the voting public by and large supported (and still supports) doing something to combat climate change (personally, I’m more concerned about adaptation policies than prevention). What can’t be agreed on is the model. It’s a not dissimilar situation to the debate over becoming a republic.

The Greens — and no one doubts their collective passion on climate change — fell victim to the nirvana fallacy: an approach that involves presenting an obviously better but unrealistic option as superior to an achievable outcome. In 2009 the Greens used the nirvana fallacy to condemn Rudd’s ETS as not green enough, largely because of the number of free permits being granted to businesses, as well as the low starting price. (The term “nirvana fallacy” was coined by US economist Harold Demsetz in 1969, and is closely related to Voltaire’s poem.)

The Greens have consistently refused to accept that their opposition to Rudd’s ETS was a mistake. Even looking back on the decision, with the benefit of hindsight, they refuse to concede the political error.

Tomorrow Greens leader Christine Milne is a guest on Australian Agenda on Sky News. Perhaps in the wake of the repeal of the carbon tax she will finally concede the mistake. But don’t hold your breath. For minor parties that only need to appeal to a fraction of the electorate, it is easier to stand on piety.”

“For a carbon-based life form the Australian Greens have demonstrated an unfathomable level of vanity, inanity and hypocrisy in roughly equal measure. Those who have followed this political movement closely might not have been surprised by its antics, but it has been remarkable to see Labor suckered in to the political black hole of imposing a carbon tax. Now, despite intransigence from the Greens and Labor, the will of the people has finally won out and the tax is gone.

The Greens’ hypocrisy is laid bare when we measure their tears now against their tactics with the Coalition in 2009 and 2010 to repeatedly block Kevin Rudd’s carbon pollution reduction scheme. Without their resistance, an internationally linked emissions trading scheme would have been well established by now, with companies paying between about $6 and $8 a tonne in line with the European scheme. This would have inflicted only a fraction of the burden we have seen the carbon tax impose on the aluminium industry, vehicle- manufacturing sector and household budgets.

The inanity of the Greens is evident because they could not grasp all this and bank an emissions trading scheme when they could. Instead, they later convinced Julia Gillard to break her promise not to impose a carbon tax. The Greens’ silliness shows no sign of letting up as they pledge to oppose the Coalition’s “direct action” plans which — while less than ideal and more expensive than necessary — still see real money spent on carbon abatement.

The Greens, again, are set to turn their back on the good in pursuit of what they perceive to be the perfect. Still, we would be foolish to expect any better from a party that exaggerates the global warming threat while campaigning against the currently viable low-emissions solutions of natural gas, hydro and nuclear power. And the vanity, the sheer vanity, to suggest that any carbon-reduction activity in a nation that produces less than 1.4 per cent of the world’s human-generated greenhouse gases will change the global climate. Science tells us Australia’s contribution can only be marginal, so any expectations of “saving the planet” must rest on this nation leading an international change of heart.

If Christine Milne thinks she can turn the trend of massive investment in new coal-fired power generation in China and India or convince the US to impose the carbon price it has resisted over the past decade, she really ought to get cracking. The rest of us are constrained to dealing with the real world.

In that real world, China’s emissions have doubled over the past decade. In India, the same process is under way a decade or two behind. While emissions rise, the scientific evidence suggests a degree or two of warming will occur this century, despite the pause thus far. Any realistic assessment will weigh the costs of more severe droughts and rising sea levels against the benefits of higher agricultural yields and fewer deadly cold snaps.

The abolition of the carbon tax removes an act of economic self-harm and political skulduggery. It will make no difference to the global climate or talks on global policy; especially if Australia meets its 5 per cent emissions reduction target through direct action. It is time for a serious, realistic and multidimensional climate debate.”