In Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), the former dictator, Robert Mugabe, permitted and encouraged a campaign of violence that drove the European farmers off the land.

Mugabe ruined his country’s agriculture, forcing the importation of food. Simultaneously, he sold diamond wealth to foreign (mainly Chinese) interests, raising money to import food – and enrich himself and some of his followers.

South Africa is rather different, but keep the Zimbabwe point in mind. The present concern for South Africa is far-reaching.

If the climate of violence in South Africa was to lead to the seizure of the land owned by the Afrikaner people and its supposed ‘re-distribution’, it may be reasonably anticipated that agriculture would collapse, bringing on famine. The gangster group that would acquire power in the African National Congress system would be obliged to feed its masses or themselves be overturned in blood. The only way to effectively do that would be the super-exploitation of gold, diamond and uranium resources which would also imply the need for a plentiful supply of cheap labour disciplined by a paramilitary police. The labour would be available from the failure of the would-be farmers. The new dictators would ally with the mining multinationals and the banksters to guarantee their rule.

Blood Diamonds

Blood Diamonds

Might it be that ‘someone’ has already noticed this appalling set of possibilities?

We should not believe that South Africa has not already seen similar machinations.

Let us go back to what the Boer War 1899 – 1902 achieved for the former British Empire. Essentially, the diamond and gold companies used their political influence to seize the resources of the two Afrikaner republics.

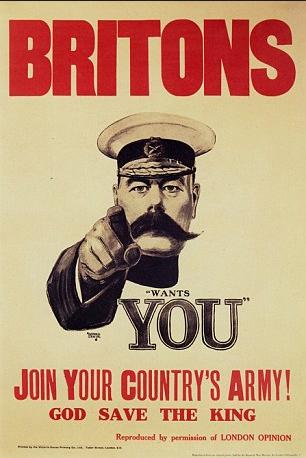

Britain’s infamous Lord Kitchener

We quote from Historia 58, 1, May/Mei 2013, pp 1-17 “Black resistance in the Orange Free State during the Anglo-Boer War “ John Boje and Fransjohan Pretorius:

“The war achieved the British objective of destroying the obdurate landowning leadership of the Transvaal and replacing it with a more compliant class of progressive farmers and professional men. This was the “revolution” of which Jeremy Krikler speaks, but this aim could only be achieved at the cost of permitting and even fostering a “rebellion” from below. With British concurrence, if not encouragement, blacks refused to work for the Boers; were armed and fought against the Boers; harassed their wives; looted their cattle; destroyed their possessions; and occupied their farms. Once the British aim of “regime change” was achieved, however, the black people they had empowered were very speedily disempowered once more. Krikler’s focus is on the Transvaal, but events followed a similar course in the Free State.”

In that scenario, the British Empire incited Africans against the whites to achieve a social result and then disarmed them. The breaking of the independent farming group which sustained Afrikaner independence meant there was no political opposition to the takeover of the resources of the Afrikaner republics. Clever indeed.