This is quoted from Australian Lieutenant John Alexander Raws’ letter home from the Western Front at Pozières Ridge with the 23rd Battalion in August 1916 just before his 33rd birthday. Battle of Pozières Ridge lasting six weeks from July 23 through to September 3 during the Allies offensive against the Germans in 1916.

The namesake is a small pastoral village, Pozières, situated in the (river) Somme valley in France. The battle for the nearby ridge, a strategic high ground on the flat river valley.

During the period of 1915-1916 the Germans turned the high ground along Pozières Ridge in to an extremely strong defensive area. From their vantage points they could see any possible allied advancement. So the Battle of Pozières Ridge was an ongoing battle as part of the great British Allied Somme Offensive of 1916 involving most of Australia’s human contribution to the war.

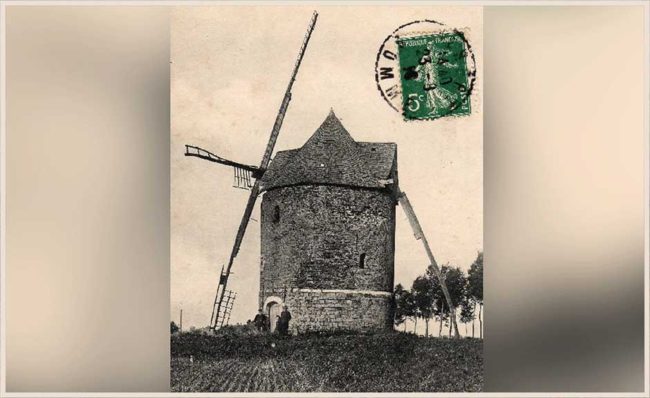

It was the scene of bitter and costly fighting for the Australian Imperial Force’s 1st, 2nd and 4th Australian Divisions in mid 1916. The ridge was referenced by an historic French windmill.

Lead Up to the Battle

On the 1st of July, 80 battalions of the British and French armies went ‘over the top’ in the Somme Valley. They advanced into heavy, enfilading machine-gun fire, brutally finding the week-long artillery bombardment had inflicted little damage on German defences. At that first day’s end, British forces had suffered 60,000 casualties, almost 20,000 dead in Britain’s greatest military disaster – ever. Australia’s would follow 18 days later at Fromelles and then Pozières.

At Fromelles on July 19, in less than 24 hours, Australia suffered 5,533 casualties – 1,917 dead; 3,146 wounded; 470 taken prisoner – our nation’s worst day ever – casualties of muddled planning and reckless decision making. Two years later, Australia’s official war correspondent C.E.W. Bean would return to walk over the ground on the day of the Armistice to think, reflect and record:

“We found the old no man’s land simply full of our dead. The skulls and bones and torn uniforms were lying about everywhere.” He described Fromelles as: “One of the bravest and most hopeless assaults ever undertaken by the AIF.” On this site today at ‘VC Corner’, is the only Australian cemetery without headstones and epitaphs. A stone wall sits in the middle of the former no man’s land inscribed with the names of 1,299 Australians with no known grave.

Then came Pozières.

On the morning of the 20th July, as the German Army surveyed the scene of their victory at Fromelles, soldiers of the Australian 1st Division arrived to replace the British on the front line south of the village of Pozières.

Positioned atop a ridge about 64 kilometres south of Fromelles, Pozières was more or less in the middle of the British Sector of the Somme battlefield.

Less than a week earlier, the southern section of the German second line near Pozières had been taken during the Battle of Bazentin Ridge. British command now saw the opportunity to complete the capture of this line in their sector by advancing northeast, through Pozières and beyond.

The British Fourth Army had attempted to take Pozières three weeks earlier, on the first day of the Somme Offensive.

They tried again on the 13 and 17 July, still with no success and suffering heavy casualties. The village was subjected to heavy bombardment during this period, destroying many of the buildings and turning the surrounding country into a wasteland, particularly around the German trench lines.

British troops had been unable to advance beyond “Pozières trench” south of the village, twice being pushed back. Their efforts to advance to the east of the village, up through what was known as the Old German Line trenches, also failed.

The Battle of Fromelles had rendered the Australian 5th Division unfit for fighting for many months to come.

So the challenge now fell to the Australian 1st Division, which like the 5th Division at Fromelles, was facing its first major battle on the Western Front.

The Australian 1st Division marched through the town of Albert, unsettled by the gilded Virgin dangling above the square. On their long march to the small village of Pozières, they were unaware of Haig’s disastrous first day on the Somme.

Sergeant Ben Champion wrote of moving from the eerie quiet of Albert into Sausage Valley, marching on to Pozières:

“..we realised at last that we were at war…. litter of all kinds. We came to an area with the sickly smell of dead bodies….half buried men, mules and horses came into view. Here was war wastage properly. Germans and British mixed together, lying in all positons and there wasn’t a man but thought more seriously of what was ahead.”

Arriving at the British front line, a trench system that in places was no more than a series of ditches, 1st Division soldiers spent 48 hours preparing for their attack, under German artillery and gas bombardment. At Pozières the 1st Division would initially succeed in occupying the village, only to become the subject of a devastating artillery bombardment said to be the heaviest experienced by Australians during the First World War.

When the 1st Division was relieved by the 2nd it had suffered more than 5200 casualties. Ahead for the Australian 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions over the next six weeks were 24,000 casualties – 6,800 dead, five Victoria Crosses.

The Battle of Pozières Ridge

During the evening and night of July 22nd, the eve of the attack, British and German artillery engaged in a fierce duel, a display of fire power that lit up the sky for miles around. The Australian 2nd Division, newly arrived at Albert three miles away, watched the bombardment from nearby high ground.

At dawn on the 23rd of July, 1916, the Australian Army AIF 1st Division attacked the German defences in Pozières village.

At 12.30am, the Allied artillery lifted its fire, striking targets behind the German front line and the first two waves of the 1st and 3rd Brigades began their assault, rapidly capturing the Pozières Trench system south of the village. The Australian 1st Division began their attack half an hour past midnight on the 23rd July, following a plan that required the 1st and 3rd Brigades to attack Pozières from the south, and advancing in three stages.

They were supported to the northwest of the Albert-Bapaume road by the British 48th Division, which attacked the German trenches to the west of the village.

45 minutes later, the Australians took their second objective, south of the Albert-Bapaume road. However, to the east, the 3rd Brigade’s advance faltered as the 9th and 10th Battalions met stiff resistance near the Old German Lines on their right.

By 4am, the Australian front line stretched diagonally across the south of the village, with the 1st Battalion at the western end, edging toward the Albert-Bapaume road, and 9th and 10th Battalions’ experiencing intense resistance.

By 7am, shortly after sunrise, scouts had reported to 3rd Brigade commanders that German infantry was massing for a counter attack in the north of the village. Allied artillery bombarded the area, inflicting heavy casualties on the Germans and dispersing the attack.

As the barrage lifted, German infantry were seen withdrawing and the 2nd Battalion, on the west flank, crossed the Albert-Bapaume road and pushed north through the ruins of the village.

By 10am, further west of the Old German Lines, Australian observers watched German troops withdrawing toward the cemetery at the northern edge of the village. The 1st Brigade pursued them, capturing more and more of Pozières, engaging in vicious close quarters fighting and taking prisoners as they advanced through the ruined buildings.

By mid-afternoon, the Allied artillery had lifted its fire still further behind the German front lines as Australian troops secured the village.

By 9pm that evening, when 2nd Brigade’s 8th Battalion arrived to reinforce the them, 1st Brigade occupied a line about mid-way through the northern part of Pozières.

As night fell on the 23rd of July, Australian soldiers digging in throughout the village were aware of their significant success – despite the difficulty in securing the Old German Lines to the east, they had succeeded in taking their objectives and now occupied an important German position in this sector of the Somme Valley.

Orders for the 24th of July were for the Australians to press their advantage by advancing further north beyond the village, toward Mouquet Farm, and east against the Old German Lines.

But this proved an impossible task. The Germans occupied a formidable position at Mouquet Farm and the Australians had trouble repositioning their troops for this new assault, in a ruined landscape now devoid of landmarks and under heavy German artillery bombardment.

At one point, 5th Battalion soldiers seized a section of the Old German Lines but were driven back by the newly arrived 18th German Reserve Division, brought in to reinforce the main counter-attack against the Australians at Pozières.

The drawn-out struggle for the Old German Lines continued for days.

German high command ordered a strong response to the loss of Pozières, the only significant gain by Allied forces on this part of the front.

As the Australians consolidated their gains the Germans opened a devastating artillery bombardment on Pozières.

Australia’s Official Correspondent to the Australian Imperial Force and later Official Historian of the war, Charles Bean, later wrote, “The German bombardment was, at first, methodical rather than intense. One battery…for example, firing directly along a deep trench just dug by the Australians on the southern side of the [Albert-Bapaume] road, pounded it systematically with about four shells a minute, breaking its sides and burying men whose comrades…constantly dug them out alive and dead. By evening parts of that trench could not even be found by the relieving companies. The southwest entrance to the village…was most heavily and continuously pounded, and the main approach route there was so lined with dead that it came to be called Dead Man’s Road.”

Meanwhile, toward the Old German Lines the Australian assault remained stalled in the face of continuing heavy resistance.

Brigadier General Sinclair-Maclagan, ordered the Battalions on the far right to renew the attack on the first line. But sustained German fire from the vicinity of the heavily fortified Pozières Windmill continued to hinder this effort.

The 10th Battalion’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Stanley Price Weir, described the fortification there as “a cement keep [which] has the appearance of a cottage and will be very difficult to take without assistance from Heavy Guns, which have not up to the present touched it.”

Several problems faced the 9th and 10th Battalions in their assault of the Old German Lines. The area had been so pummelled by artillery fire that orientation was difficult and the two parallel German trench lines were not easily visible.

Beneath the trenches were deep dugouts, impervious to the Allied bombardment, and occupied by German troops ready to emerge and engage the Australians. The Germans were also supported by concealed machine guns and by fire from the fortifications around the Pozières windmill. This well defended position also meant that German fire could continue targeting Australian soldiers attempting to secure the eastern side of Pozières.

Over the next two days, German and Allied artillery bombarded what remained of the shattered village of Pozières, until this part of the front resembled a lunar landscape.

The ferocious barrage was visible for miles, throwing up dust, smoke and debris. Some Australians were outside the line of German fire, others sheltered in the deep dugouts vacated by the German soldiers while others still had to endure the terrible shell fire in the shelter of shell holes or broken trenches.

The severity of the bombardment indicated the likelihood of a strong German counter-attack, which the Australians expected would come on the evening of the 25th July. But the fighting in the Old German Lines that morning between the Australian 5th Battalion and the German 18th Reserve Division, the exhausting artillery duel, and the enormous strain of the past three days compelled the Germans to abandon the attack.

Then the 2nd division took over and the offense against the German positions continued.

On the 26th of July the Australians fought to consolidate the ground taken by the 1st Division to extend toward further objectives beyond Pozières Ridge. It was during this phase of the battle that the Australians faced the heaviest and most prolonged series of artillery barrages ever experienced by the AIF. During this action the 2nd Division lost 6,848 officers and men.

Emerging from the rubble of Pozières on the morning of the 27th to be relieved by the Australian 2nd Division, the survivors of the Australian 1st Division were described as being so dazed they appeared to be walking in a dream. The 1st Division had suffered more 5282 casualties in their first tour of Pozières.

The 1st and 2nd Divisions were once more thrown into the battle and, although their numbers were severely depleted, they managed to hold the ground taken around the Windmill, now obliterated. Moquet Farm, though, was a different matter. After 7 sustained attacks, the area remained in German hands.

After 3 days of intense fighting, the village was taken from the German defence by the Australians. The 4th Division was brought into the line and fought to secure the areas around the Windmill and Moquet Farm. The conditions were horrendous, though, and although some objectives were taken, little ground was captured.

The 2nd Division took over from the 1st and mounted two further attacks – the first, on 29 July, was a costly failure; the second, on 2 August, resulted in the seizure of further German positions beyond the village. Again, the Australians suffered heavily from retaliatory bombardments. They were relieved on 6 August, having suffered 6,848 casualties.

The 4th Division was next into the line at Pozières. It too endured a massive artillery bombardment, and defeated a German counter-attack on 7 August; this was the last attempt by the Germans to retake Pozières Ridge.

Exhausted, the Australians were brought out of the line in early September. 12,130 Australians were sacrificed in just four days following attrition orders by some British elitist map gamer.

Battle Aftermath

In all, there were over 23 000 Australian casualties in the six weeks of fighting – almost the same number as the whole Gallipoli campaign. In fact the Australian soldiers who fought and died at Pozières were for the most part survivors of the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign.

Thrown into Battle at Pozières, the men of the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions suffered what is said to have been the most concentrated artillery barrage of all time. With German Forces on three sides, and their own artillery firing from the rear, these men lived and fought in a constant rain of shells.

Aghast, Bean wrote of Pozières: “The men are simply turned in there as into some ghastly mincing machine.”

The inexperienced AIF was ill-prepared for the Imperial German Army. Less than a third of its troops had fought on Gallipoli. France was now Germany’s western border. With two years on the Western Front, the battle hardened Germans were better trained and equipped. Germany’s complex of trenches, fortified villages and belts of barbed wire marked no man’s land strategically covered with machine-guns and German artillery.

Sergeant Alexander Ross of Australia’s 57th Battalion revealed the Australian character, volunteering to recover wounded from no man’s land. Captain Hugh Knyvett was with him.

“We found a man on the German barbed wire….so badly wounded that when we tried to pick him up, one by the shoulders and the other by the feet; it almost seemed that we would pull him apart.

Blood was gushing from his mouth, where he had bitten through lips and tongue, so that he might not jeopardize, by groaning, the chances of some other man who was less badly wounded than he. He begged us to put him out of his misery, but we were determined we would get him his chance, though we did not expect him to live. But the sergeant threw himself down on the ground and made of his body a human sledge.

Others joined us, and we put the wounded man on his back and dragged them thus across two hundred yards of No Man’s Land, through the broken barbed wire and shell-torn ground, where every few inches there was a piece of jagged shell, and in and out of the shell-holes.

So anxious were we to get to safety that we did not notice the condition of the man underneath until we got into our trenches; then it was hard to see which was worst wounded of the two.

The sergeant had his hands, face, and body torn to ribbons, and we had never guessed it, for never once did he ask us to’wait a bit’. Such is the stuff that men are made of.”

December 1916: Unidentified men of the 5th Division partaking in cigarettes and resting by the side of the Montauban road, near Mametz, (Picardie, Somme, Albert Combles/Montauban area) while en route to the trenches. Most of the men are wearing sheepskin jackets and woollen gloves and are carrying full kit and .303 Lee Enfield rifles.”

December 1916: Unidentified men of the 5th Division partaking in cigarettes and resting by the side of the Montauban road, near Mametz, (Picardie, Somme, Albert Combles/Montauban area) while en route to the trenches. Most of the men are wearing sheepskin jackets and woollen gloves and are carrying full kit and .303 Lee Enfield rifles.”

The following is a famous extract from a letter by Australia’s 2nd Lieutenant John Alexander Raws of the 23rd Battalion, who in a very graphic account, describes a scene during the battle.

“… we lay down terror-stricken along a bank. The shelling was awful … we eventually found our way to the right spot out in no-man’s-land. Our leader was shot before we arrived and the strain had sent two other officers mad. I and another new officer took charge and dug the trench. We were shot at all the time… the wounded and killed had to be thrown to one side … I refused to let any sound man help a wounded man; the sound had to dig … we dug on and finished amid a tornado of bursting shells … I was buried once and thrown down several times … buried with dead and dying. The ground was covered bodies in all stages of decay and mutilation and I would, after struggling from the earth, pick body by me to try and lift him out with me and find him a decayed corpse … I went up again the night and stayed up there. We were shelled to hell ceaselessly. X- went mad and disappeared… there remained nothing but a charred mass of debris with bricks, stones, girders and bodies pounded to nothing … we are lousy, stinking, unshaven, sleepless … I have one puttee, a man’s helmet, another dead man’s protect dead man’s bayonet. My tunic rotten with other men’s blood and partly spattered with a comrade’s brains”.

John was killed in action on 23rd August 1916 two weeks before his 33rd birthday. His younger brother, Lieutenant Robert Goldthorpe Raws (30) was also killed at Pozières. Robert was also in 23rd Battalion, killed instantly by a shell on the 28th July 1916, 26 days before his brother.

Immediately after all that, Australia’s Prime Minister, Billy Hughes tried to introduce conscription because he was running out of volunteers. Australians at home rejected his referendum on 28 October 1916.

Lest We Forget

“We’re All Australians Now”

Australia takes her pen in hand

To write a line to you,

To let you fellows understand

How proud we are of you.

From shearing shed and cattle run,

From Broome to Hobson’s Bay,

Each native-born Australian son

Stands straighter up today.

The man who used to “hump his drum”,

On far-out Queensland runs

Is fighting side by side with some

Tasmanian farmer’s sons.

The fisher-boys dropped sail and oar

To grimly stand the test,

Along that storm-swept Turkish shore,

With miners from the west.

The old state jealousies of yore

Are dead as Pharaoh’s sow,

We’re not State children any more —

We’re all Australians now!

Our six-starred flag that used to fly

Half-shyly to the breeze,

Unknown where older nations ply

Their trade on foreign seas,

Flies out to meet the morning blue

With Vict’ry at the prow;

For that’s the flag the Sydney flew,

The wide seas know it now!

The mettle that a race can show

Is proved with shot and steel,

And now we know what nations know

And feel what nations feel.

The honoured graves beneath the crest

Of Gaba Tepe hill

May hold our bravest and our best,

But we have brave men still.

With all our petty quarrels done,

Dissensions overthrown,

We have, through what you boys have done,

A history of our own.

Our old world diff’rences are dead,

Like weeds beneath the plough,

For English, Scotch, and Irish-bred,

They’re all Australians now!

So now we’ll toast the Third Brigade

That led Australia’s van,

For never shall their glory fade

In minds Australian.

Fight on, fight on, unflinchingly,

Till right and justice reign.

Fight on, fight on, till Victory

Shall send you home again.

And with Australia’s flag shall fly

A spray of wattle-bough

To symbolise our unity —

We’re all Australians now.

– An open letter to the troops, 1915, by A.B. Paterson.