Article sourced from Perth Now, by Stephen McMahon, January 31, 2012

“AUSTRALIA’s two-speed economy is about to become further polarised as the investment boom above the “Brisbane Line” moves into overdrive, according to new research.

The latest Deloitte Investment Monitor reveals that the value of projects under construction has soared 43 per cent to $415.5 billion.

Mining companies are driving the boom, looking to cash in on the surge in demand from China and India.

The report comes as an $8 billion legal battle looms between mining magnate Clive Palmer and Queensland’s government over the development of a rail link between mines and ports.

Mining projects account for almost half of the investment projects under construction, including Origin Energy’s $19.6 billion liquefied natural gas project at Gladstone, south of Rockhampton.

The Deloitte report says the continuing surge in infrastructure development and energy projects would provide a healthy buffer against any global slowdown in 2012.

But it warns Australia’s economic future is “geographically skewed”: $323.5 billion, or 57 per cent, of the investment pipeline is committed to projects above the so-called Brisbane Line, while 80 per cent of the population work elsewhere.

“The Brisbane Line could be used to characterise Australia’s economy,” said the report’s key author, Deloitte partner David Rumbens.

“It is the economic activity to the north and west which is defining Australia’s prospects, and protecting the country against the weak global economic environment.”

Mr Palmer yesterday launched an $8 billion lawsuit against rail operator QR National, saying there was a political conspiracy to steal his plans to build a rail line.

Mr Palmer claims to have been drafting agreements with QR National about developing a 471km rail link as late as last week, before the Government granted “significant project” status to QR National’s own proposal.

The railway will link mines in the Galilee and Bowen basins to coastal ports.

QR National is more than one-third owned by the Queensland Government.

China First — a Clive Palmer-owned exploration and coal mine development company — said it was an outrageous decision. It is filing a damages claim in the Queensland Supreme Court and seeking injunctions against QR National.”

Treacherous History of The Brisbane Line

The story behind the Brisbane Line controversy – the idea that parts of Australia above a line just north of Brisbane would be surrendered to the Japanese without firing a shot. It is a tale of political deceit, manipulation, cowardice and betrayal by politicians on all sides for electoral gain, culminating in the scapegoating of innocent army officers.

The story behind the Brisbane Line controversy – the idea that parts of Australia above a line just north of Brisbane would be surrendered to the Japanese without firing a shot. It is a tale of political deceit, manipulation, cowardice and betrayal by politicians on all sides for electoral gain, culminating in the scapegoating of innocent army officers.

The ruling United Australia Party under “Honest Joe” Lyons and Menzies were notorious appeasers of both Hitler and fascist Japan, and little, if anything serious was done to prepare for a war which some prominent Australians, such as BHP’s Essington Lewis, had concluded as early as 1934, was inevitable. In the mid-1930s the Japanese purchased almost as much wool – Australia’s main export – as did the British, and therefore developed increasingly intimate ties into the still rural-centered pastoral and banking oligarchy. Japan’s ultimate aim was complete hegemony in Asia and unchallenged supremacy in the western Pacific. Her strategic objectives were the subjugation of the Philippines and the capture of the immense natural resources of the Netherlands East Indies and Malaya. The conquest of the Philippines became an immediate military necessity. The Islands represented America’s single hope of effective resistance in Southeast Asia.

While the fighting in the Philippines was retarding the Japanese general advance, Australia was being prepared as a major Allied and United States base. A convoy en route to the Philippines from the United States at the outbreak of hostilities had been diverted to Australia. While at sea on 21 December, the troops were formed into Task Force South Pacific, and after debarking at Brisbane they were designated, on 5 January 1942, United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA).

General MacArthur arrived in Australia from the Philippines on 17 March 1942. MacArthur had finally been convinced that a counteroffensive could not be organized in the Philippines and that he would have to use Australia as his new base of operations. The Australian Government immediately nominated General MacArthur for the post of Supreme Commander in a proposed new Allied command, the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). In this capacity he would have command of all Allied forces in the general region of Australia and New Zealand as far north as the equator and would be responsible to the British and American Combined Chiefs of Staff.

The Allied commanders in Australia considered that the next enemy moves would be directed against Darwin and Port Moresby, both already under air attack. The occupation of Darwin might be designed merely to deny it to the Allied forces or as one stage in a general offensive against northwest Australia and the Gulf of Carpentaria. An attack on Port Moresby would eliminate it as a threat to the flank of an advance from Rabaul southward against the east coast of Australia or New Caledonia and the sea and air routes from the United States.

The combined United States and Australian forces were obviously insufficient for the protection of the whole of a vast continent, almost equal in size to the United States and with a coast line 12,000 miles in length. Concentration in any area to oppose Japanese landings was exceedingly difficult because of the great distances to be covered and the inadequate transportation facilities. The road and rail network of Australia was of limited capacity and of varying gauges and did not permit the rapid movement of troops. Principal routes frequently paralleled the coast and were vulnerable to amphibious attack. Darwin possessed no rail connection with the rest of the country. Port Moresby and Tasmania depended solely upon sea lines of communication and their control by friendly air and naval forces.

The Australians disposed the bulk of their forces in the general region around Brisbane and Melbourne where most of the industries, the principal food producing centers, and the best ports, were located. The area was all-important to the country’s war effort, and its defense was the prime consideration of its military authorities. Small forces were stationed in Tasmania and Western Australia and at Darwin, Port Moresby, Thursday Island, and Townsville. Because of their relative isolation, the retention of these points on the outer perimeter depended largely upon their garrisons, none of which was strong enough to oppose a major assault successfully. Reinforcing them was impossible, as additional troops could be drawn only from the vital southeastern region which, in the opinion of the Australian Chiefs of Staff, was itself inadequately held. Withdrawal from the outlying areas was equally out of the question. Their importance warranted an effort to hold them as long as possible, and the destructive effect of such an evacuation on public morale also had to be considered.

The Japanese used the bombing of Darwin and other northern towns as a means of drawing off large military resources which could not be committed to the campaign in Papua and New Guinea. A Japanese invasion of Australia would not have been through a Perth or Darwin axis. These points could be essentially neutralised by minor attacks. The focus of invasion would have been the south-eastern “boomerang” in which the most productive primary, secondary and tertiary industries were located – the zone in which most Australians lived.

By May 1942, the fall of Corregidor, the collapse of resistance in the Philippines, and the defeat in Burma, brought about a new situation in this theater. Japanese troops in the Philippines, in Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies were susceptible of being regrouped for an offensive effort elsewhere. The Japanese Navy was as yet unchallenged and is disposed for further offensive effort. A preliminary move was under way against New Guinea and the lines of communications between the United States and Australia.

General MacArthur told FDR that “If serious enemy pressure were applied against Australia prior to the development of adequate and balanced land, sea, and air forces, the situation would be extremely precarious. The extent of territory to be defended is so vast and the communication facilities are so poor that the enemy, moving freely by water, has a preponderant advantage….”

What would have happened if Japan had won the battles for Papua and the Solomon islands? In the event of a delayed response from the United States the Japanese would almost certainly have attempted to invade Australia. This would have been only possible if they were able to withdraw troops from China and find sufficient shipping to land the troops on the east coast. A successful lodgement would have extended their supply lines further and only in the event of a rapid rout of Australian forces could the invasion have been sustained. Even in the event of Australia being denied the United States as a fixed aircraft carrier, the island hopping and naval strategy could have been begun from New Zealand and the American Pacific territories. Japan’s defeat might have been delayed but it would still have occurred.

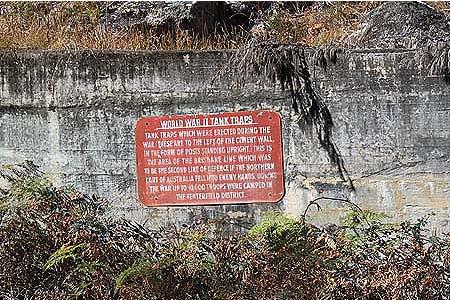

For two generations, many Australians believed that the Menzies wartime government planned to surrender parts of Australia to the Japanese without firing a shot. The forfeiture of land was to be above a line drawn just north of Brisbane. This information was disclosed to a stunned public by the Labor Party halfway through 1943. Eddie Ward, the member for East Sydney, accused the previous Menzies government of having a plan to abandon northern Australia to the Japanese should they invade from the north. That year, the ALP won a landslide electoral victory, ostensibly on the strength of these revelations. Even today, older Australians point to tank traps and the like in various parts of northern Australia that they firmly believe are physical evidence of this non-existent Brisbane Line.

The remains of concrete tank traps can be seen near Tenterfield in New South Wales. They were used to span a bottle neck in the Clarence River Valley east of Tenterfield in northern New South Wales, in an area known as Paddys Flat. The concrete pillars are still visible in and beside the river near the crossing. Dallas indicated that this was part of the so-called “Brisbane Line” defence plan. Dallas also described some well known tank traps just north of Tenterfield on the Bald Rock Road. They consist of log pillars and a concrete wall in the valley. The sign posts on the road claim that they formed part of the “Brisbane Line” defences.

The remains of concrete tank traps can be seen near Tenterfield in New South Wales. They were used to span a bottle neck in the Clarence River Valley east of Tenterfield in northern New South Wales, in an area known as Paddys Flat. The concrete pillars are still visible in and beside the river near the crossing. Dallas indicated that this was part of the so-called “Brisbane Line” defence plan. Dallas also described some well known tank traps just north of Tenterfield on the Bald Rock Road. They consist of log pillars and a concrete wall in the valley. The sign posts on the road claim that they formed part of the “Brisbane Line” defences.

Menzies never had a ‘Brisbane Line’ plan and had never been given such a plan by his military advisers. This did not stop the Labor party and the extreme left from using this as a charge that Menzies was a pro-fascist and had not bothered to develop Australia’s defence. The use by Curtin and the Labor party of the ‘Brisbane Line’ myth as an electoral weapon was an act of overweening deceit, while the wartime use of the myth by Ward, when Australia was still under threat, was an act that bordered upon treason. The public’s general strategic ignorance, military weakness and the loss of confidence in Britain provide an adequate explanation of why exploitation of the “Brisbane Line” myth was so profound.

In fact, discussions between the Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy High Commands on the whole issue of future operational policy regarding Australia came to a head in early 1942. These discussions had been initiated by the Navy as early as February 1942, following the invasion of the Bismarcks, but had produced no concrete results owing to a sharp divergence of opinion with the Army. The dominant section of the Navy thus demanded a complete change-over from the original defensive concept of the southeastern front to one in which it would become a stepping-stone to further expansion into and conquest of Australia.

The Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters strongly opposed over-extension of army commitments in that area and rejected the proposed invasion of Australia as a reckless undertaking far in excess of Japan’s capabilities. Ground force strength required for such an operation was estimated at 12 combat divisions, which would strip other fronts considered more important by the Army. Also, Japan’s available shipping, the Army contended, was unequal to the logistical task of transporting and supplying a force of such size.

On the basis of its estimate that the United States Fleet would not recover from its Pearl Harbor losses quickly enough to assume the offensive in the Western Pacific before the end of 1942, the Navy, particularly the staff of the Combined Fleet, contended that Japan should not switch to a defensive policy of merely holding on to its already-established gains. A reversion to negative policies based on the original war plans, it was argued, would nullify Japan’s early victories and invite a prolonged stalemate in which America’s growing material strength would spell Japan’s defeat.

In support of this thesis, the Fourth Fleet command at Truk pointed to the gradually increasing flow of American war materiel, especially aircraft, to Australia, warning that this clearly indicated Allied intent to build up the subcontinent as a powerful counter-offensive base. Were this intent allowed to materialize, the Navy’s existing defense line from eastern New Guinea to the Bismarcks and northern Solomons might prove inadequate to check an Allied counter-thrust.31 Consequently, the Navy insisted that Japan’s wisest course lay in remaining actively on the offensive in the southeastern area, with the ultimate objective of attacking Australia itself.

In addition to these strategic considerations, the Navy proponents of an Australian invasion also advanced the political advantages to Japan of knocking Australia out of war and the added economic strength which would be gained through the acquisition of Australian wool, wheat, fertilizers and other resources.

As a result of adamant Army objection, the idea of a direct assault on Australia died in the discussion stage. Influenced by the Doolittle raid on Tokyo of 18 April 1942, Imperial General Headquarters on 05 May 1942 issued orders for the execution of operations against Midway and the western Aleutians. This crucial decision, which was taken at the strong insistence of the Combined Fleet, swayed the whole future course of the war.”

Source: http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/australia/brisbane-line.htm