I will never forget the armistice – it was a day of hard, smelly, nauseating work. Those of us assigned to pick up the bodies had to pair up and bring the bodies in on stretchers to where the graves were being dug. First we had to cut the cord of the identification disks and record the details on a sheet of paper we were provided with. Some of the bodies were rotted so much that there were only bones and part of the uniform left. The bodies of the men killed on the nineteenth ( it had now been five days ) were awful. Most of us had to work in short spells as we felt very ill. We found a few of our men who had been killed in the first days of the landing.

This whole operation was a strange experience – here we were, mixing with our enemies, exchanging smiles and cigarettes, when the day before we had been tearing each other to pieces. Apart from the noise of the grave-diggers and the padres reading the burial services, it was mostly silent. There was no shelling, no rifle-fire. Everything seemed so quiet and strange. Away to our left there were high table-topped hills and on these were what looked like thousands of people. Turkish civilians had taken advantage of the cease-fire to come out and watch the burial. Although they were several miles from us they could be clearly seen.

The burial job was over by mid-afternoon and we retired back to our trenches. Then, sometime between four and five o’clock, rifle-fire started again and then the shelling. We were at it once more.

[Albert Facey, A Fortunate Life, Ringwood, 1984, p.268]

As gunfire ceased on the Western Front on the morning of November 11, 1918, Australia’s first war correspondent Charles Bean observed “the gates to the future silently opened”. The armistice which secured the end of World War I had been signed at dawn, marking the conclusion of a four-year conflict that had claimed more than 60,000 Australian lives.

Back home, the celebrations, no matter how joyful, could not make up for the devastating impact of the war, according to military historian, Ashley Ekins Head of the Military History Section at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Ekins:

“The losses, of course, were extreme — 60,000 men that really couldn’t be easily replaced. In many ways, Australia in the interim years was a nation in mourning.”

Still left to arrange was the huge task of bringing troops home — an exercise that would take nearly a year.

Once home, they would be faced with the challenge of readjusting to civilian life.

Etkins:

“The fact was these men came home, mostly, completely changed by the experience. They had been out of sight — never out of mind — on the other side of the world, fighting a war that was probably inconceivable to most Australians. The people at home had never really known what those men had done.”

Every Australian should visit the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, younger the better, starting with its considerable website: https://www.awm.gov.au/

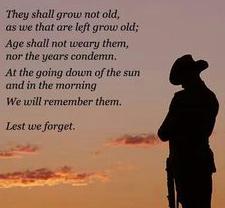

Lest We Forget