The following article is an abstract of a discussion paper by David Martin of the Australian National University on Noel Pearson’s 2001 proposals for Aboriginal welfare reform.

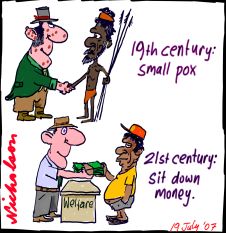

“Aboriginal lawyer, activist and social commentator Noel Pearson has recently argued that the current mode of delivery of welfare services to Aboriginal people is deeply antithetical to their interests and wellbeing. Central to his scheme for policy change and improved welfare outcomes are two core propositions. The first is that the ‘passive welfare’ policies instituted in Aboriginal communities over the past three decades, with no demands for reciprocity and responsibility on the part of welfare recipients, have promoted detrimental relations of passivity and dependence which are now deeply embedded within Aboriginal societies.

Pearson’s second key proposition is that addressing the dysfunctional consequences of the welfare system for Aboriginal people will require structural change. In particular, new institutions for Aboriginal governance, both formal and informal, will need to be developed. It is through reform of the existing institutional arrangements between government and Aboriginal communities, and through these formal and informal Aboriginal institutions, Pearson argues, that the principles of reciprocity and individual responsibility necessary to leach the ‘poison’ from welfare resources can be instituted and implemented.

Pearson’s arguments should be seen as a welcome and politically innovative contribution to a policy debate of fundamental importance. The status quo in welfare policy, at least for remote Aboriginal Australia, is not sustainable. However, on the basis of ethnographic evidence from Cape York and other north Queensland Aboriginal communities—the region on which Pearson’s policy proposals are centred—this Discussion Paper suggests that certain of Pearson’s underlying assumptions need careful re-examination and further development, and that the evidence poses certain difficulties for the practical implementation of his proposals.

In particular, the ethnography from Cape York and elsewhere suggests that certain widespread Aboriginal values and practices may be inimical to the kinds of social and attitudinal changes which Pearson is advocating and, further, that these values and practices have not simply arisen as the consequence of the experience of colonialism or the introduction of welfare. This then raises the question of the sources of the moral suasion and authority necessary to demand and implement social change in Aboriginal societies. Pearson proposes that these lie variously within ‘families’ and other local groups and ‘communities’. This view is challenged here, with the argument that such contemporary groupings do not have the requisite moral and political authority over individuals. If this is the case, it creates a dilemma for Pearson’s scheme, for if social and attitudinal changes are necessary, whence can they be driven?

The answer may lie in the new forms of Indigenous governance and leadership which Pearson proposes. However, these would involve significant changes within the Indigenous polity, which may be beyond the capacity of Indigenous groups themselves to institute. Facilitation and support from external sources, including government, may be required. However, the involvement of government in social change would carry its own risks, since despite rhetorical support for Indigenous self-determination, government is inherently incapable of moving beyond its own dominating rationale.”

In 2004, West Australian Aboriginal leader Patrick Dodson met with Noel Pearson, jointly announcing backing mutual obligation and the move away from welfare dependency, as part of finding solutions to problems affecting Aboriginal communities.

“We want to make sure that the mutual obligation social reform policy and principles are part of a real negotiation in the way that they seek to assist the Indigenous communities come to terms with the poverty and the suffering and the pain that is in our communities,” Mr Dodson said. “We want to make sure that people are able to enter into this in a way that is not just about changing our behaviour, but is also about changing the public sector behaviour.”

The Block in Redfern, inner Sydney

The Block in Redfern, inner Sydney

By and large, white Australia has bought the now dominant narrative that self determination has been a failure and that it is high time that Aboriginal individuals take responsibility.

For Noel Pearson, personal and community responsibility across Aboriginal communities have collapsed. This is because of long-term dependence on passive welfare (“welfare poison”, he calls it) and deeply entrenched destructive behaviour that tolerates excessive alcohol abuse, domestic violence and school absenteeism.

So in 2007, Noel Pearson conceived The Cape York Welfare Reform Trial (CYWRT) as a tripartite agreement between the Australian and Queensland governments and his organisation, the Cape York Institute for four Aboriginal communities across Cape York: Aurukun, Coen, Hope Vale and Mossman Gorge, covering a total Aboriginal adult population of about 1,600 people.

Pearson has made his goal clear: he wants to fundamentally restructure the social norms of Aboriginal people on Cape York. The Welfare Reform Trial has set out to restructure the norms of Aboriginal people on Cape York, moving them from welfare dependence to taking part in the economy.

The trial is a carefully calibrated and innovative social policy instrument. It aims to restore positive social norms and re-establish local Indigenous authority; move communities and individuals from welfare dependence to productive engagement in the “real” economy; and move individuals and families from social housing to home ownership.

But unlike Howards’s Northern Territory Emergency Response Intervention, income management coverage in the Cape is not blanket. It is highly discretionary depending on the recommendation of local commissioners in trial communities. The trial encompasses education reform and a political campaign to gain stronger property rights for Aboriginal land owners, so they can enhance their economic development prospects. This broader ambit has been spearheaded by Noel Pearson and the Cape York Institute.

Ultimately, the success or failure of CYWRT will need to be assessed by participating communities.

In September 2014, Prime Minister Tony Abbott visited the Gunyangara community in East Arnhem, Northern Territory and met with Gumatj clan leader, 66-year-old Galarrwuy Yunupingu, saying:

“I’m acutely conscious of the fact that, at least since the 1960s, official Australia has been full of good intentions towards indigenous Australia, but the good intentions have only fitfully and spasmodically and imperfectly been translated into better outcomes for people.”

Many challenges remain. Yolngu Business Enterprises, a private company set up to train, employ and provide career opportunities to Yolgnu people across its 26 clans, has 140 employees but only 20 per cent are indigenous.

At the community of Gunyangara, boss Glenn Aitchison of Yolngu Business Enterprises which employs local Aborigines says the “huge” barriers to employment include low literacy and numeracy skills, substance abuse, welfare dependency, overcrowded housing (overwhelmingly occupied by those not working who “humbug” those who are) and cultural obligations.