Percy Reginald Stephensen (20 November 1901 – 28 May 1965) was an Australian writer, publisher and political activist, first in rebellion for the Communists, then later in home wisdom for Australian Nationalists.

P.R. Stephensen was born in Maryborough, rural Queensland. He attended the University of Queensland, where he joined the Communist Party in 1921 and got nicknamed ‘Inky‘ from his ardent activist writing – the original Australia First blogger, which one can well relate to and respect.

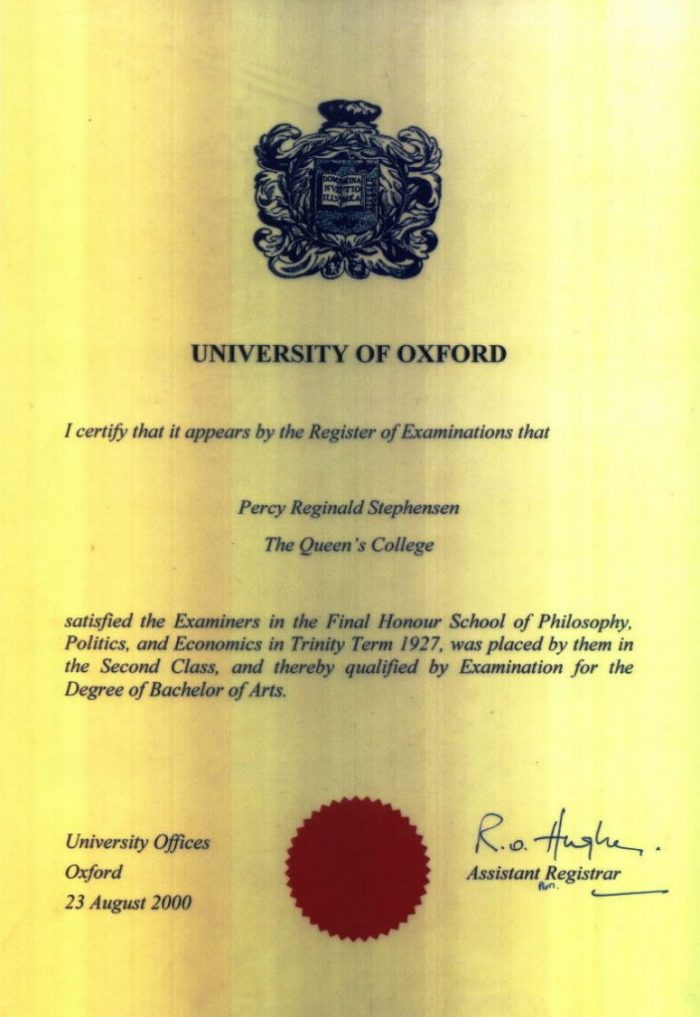

P.R. Stephensen gained a second-class honours degree in Modern Greats at Queen’s College, Oxford where he studied as a Rhodes Scholar and was a member of the university branch of the Communist Party with A. J. P. Taylor, Graham Greene and Tom Driberg.

He was a friend of D H Lawrence and edited the first uncensored version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He was also friends with Aldous Huxley.

His most significant work was The Foundations of Culture in Australia (1936), which led to the foundation of the Jindyworobak Movement.

Between the world wars, his Fellowship of Australian Writers released a document that advocated disconnection with the United States and stated, “US comics promoted demonology, witchcraft and voodooism, with superman part of a raving mad view of the world.” And of American musicals and minstrel shows, “the American negro, with his jungle is not welcome here.”

He was a member of the Australia First Movement whose magazine The Publicist he helped found in 1936 and edited from 1941-1942. He was noted for his anti-semitic views in this period. At this time, Stephensen and his colleague J.B. Miles financed the first Aboriginal publication, The Abo Call, which was written and edited by Aboriginal activist Jack Patten.

Stephensen was a prolific author. He published over 30 books, as well as translations of works by Vladimir Lenin and Friedrich Nietzsche. He also produced nearly 70 books ghostwritten for Frank Clune.

A Discussion concerning Percy Stephensen and the Australia First movement – Vitally Useful

by Jim Saleam https://unitednationalistsaustralia.wordpress.com/

‘My friends in Nationalist Alternative (NA) have reviewed an early work about The Publicist magazine, the Australia-First Movement, its founder W.J. Miles and its driving intellectual force – Percy ‘Inky’ Stephensen. See: https://www.natalt.org/2017/10/31/ghosts-australia-first-movement/

We go back in time to the establishment in 1936 of The Publicist magazine by Miles and Stephensen and its call for an Australia-First political movement, something finally and briefly realized in 1942. Yet the movement was ultimately suppressed, dubbed disloyal in a time of war, with many of its supporters interned, although later exonerated of wrong-doing, by a commission of inquiry.

I would reason it is pertinent for nationalists to consider this Australia-First experience and P.R. Stephensen’s political philosophy. In particular, given the emergence of all sorts of new patriotic and potentially nationalist movements across the country today, it may be necessary to go back in time to that movement to establish some of our traditions.

No modern movement drops from the sky and men such as Miles and Stephensen and the intellectual coterie they drew together back then were not only pushing a vision of Australian independence but were defining the Australian cultural identity. They laid foundation stones, one among many for us in the present, to build upon.

Of course, I have maintained a keen interest in Inky himself. No, it’s not because we attended the same high school or went to the same university or some such. Yes, I was later quirky enough to go out of my way to have his Oxford University degree finally issued to him (Stephensen passed his exams in 1926 but declined to pay the one pound to have it conferred).

Rather, it was because I was introduced to his monumental The Foundations of Culture in Australia in 1977 courtesy of a nationalist student, who thought a struggling group of young nationalists should read it. Our small group understood at once it was a part of our vital cultural lore.

When we met Dora Watts, one of P.R.Stephensen’s followers, we learned a little first hand of the man himself and the mission of Australia-First. Much later, some nationalists published some of P.R.Stephensen’s works, including the Foundations, online.

See: http://home.alphalink.com.au/~radnat/stephensen/index.html

My friends in Nationalist Alternative (NA) have reviewed an early work about The Publicist magazine, the Australia-First Movement, its founder W.J. Miles and its driving intellectual force – Percy ‘Inky’ Stephensen.

The Foundations of Culture in Australia would of itself have placed P.R.Stephensen in an Australian pantheon of culture-heroes and it remains essential reading even today.

Who are the Australians?

It is Race and Place. They are Europeans drawn wherever, but they are native to the soil in self-definition, a new nationality.

Simplicity!

NA observes that the Australia-First push around Miles and Stephensen emerged at a singular time in European history.

It was the era of fascism.

Fascism was then the challenge to the conservative ‘Right’ and it was the sworn enemy of the communist movement.

And as more than one commentator has said, defining fascism became a sort of Grail Quest that bedevilled for decades.

There is a 1990’s definition that bewitches, one offered up by the English political scientist, Roger Griffin:

“Fascism is a political ideology whose mythic core in its various permutations is a palingenetic form of populist ultra-nationalism.”

(The word “palingenetic” in this case refers to a concept of national rebirth.)

The definition drags in all the variants from country to country and within each country during that era of fascism (1919 – 1945). It is the Grail because, pretty much, it grasped the concept. Fascism could appear with different seeming external qualities from place to place and so on, the different historical material in its baggage and so on, but it was still the same beast.

Percy Reginald Stephensen – suave, eh?

Percy Reginald Stephensen – suave, eh?

The debate over fascism is back hard in Australia, not just because the Antifa and the Trotskyites turn up all patriot and nationalist events to scream ‘fascist’ at them, but because new ‘Alt Right’, ‘Traditionalist’ and other pro-nationalist groups have pondered over fascism’s place in Australian history.

Then, of course, there are a few neo-Nazi fetishists fixated upon one particular version of fascism and who play jack-in-the-box at the nationalists from time to time – and whom the media like to indulge. Yet, the new legitimate people want to know what is relevant and what is not.

Quite right!

So, it follows, that in establishing a basis for contemporary action, all suitable grounding-material must be found.

The Foundations of Culture in Australia would of itself have placed P.R.Stephensen in an Australian pantheon of culture-heroes and it remains essential reading even today. Who are the Australians? It is Race and Place. They are Europeans drawn wherever, but they are native to the soil in self-definition, a new nationality.

Simplicity!

I note that the NA writer said that The Publicist and the Australia-First were “pro-Axis, that they had sympathy for “National Socialism”. But was it ever really that simple?

With respect, I don’t think so. The clue to understanding Australia-First generally and P.R. Stephensen, in particular, might be to appreciate that he had a background in the Communist Party in the 1920s and he learned of Lenin’s principle of ‘revolutionary defeatism’.

That basically means that a communist party could permit the defeat of its own country in a war if the defeat led to revolution. It is my conclusion Stephensen took that one on board and jigged it.

It became that the humbling of the British Empire could produce Australian independence. Possibly so. Dangerous, but possible.

Who could humble the Empire?

Did the likely tool become fascism? Could Percy Stephensen think this?

I would say inevitably – he did. The Publicist did not submit to that baleful modern habit of putting a half-naked woman on the cover

When we study the aggressive nationalism of The Publicist in the 1930s, we can also observe its interest in assessing fascism not unfavourably, but almost always within the prism of war, Britain, Australia.

Of course, the Australia-First circle opposed any Australian involvement in a European war whomsoever caused it, but they did observe that some imperial spokesmen were quite attuned to going to war against Germany and Italy and they condemned them.

Were they wrong? I don’t believe so and I note John Curtin, Hero of the Nation in war – thought the much the same in the 1930’s. Curtin had also admired the social achievements of the fascist powers, but The Publicist, always provocative, went one further and published one of Hitler’s ‘peace speeches’ which may well have pushed the envelope!

Was The Publicist ahead of public opinion by suggesting Britain wanted to drag Australia into its European war while dangers lay elsewhere?

When we study the aggressive nationalism of The Publicist in the 1930s, we can also observe its interest in assessing fascism not unfavourably, but almost always within the prism of war, Britain, Australia. The advent of war in September 1939 put the Publicist in a bit of a bind, but it did not stop its nationalist advocacy. Were there examples of policy to draw on?

Were Miles and Stephensen aware of the case of Ireland?

The Irish Free State did not go to war in 1939, although it was part of the Commonwealth.

Ironically, the IRA took German money to put pressure on Ireland to press for “reunification” with Ulster, while the Irish state used the tangled issue of its neutrality to gain much more freedom from Britain and even curtailed the IRA’s very terrorism to win British concessions!

Did anyone suggest the IRA or the Irish Free State were fascists? Yes, it was a dangerous game too and the Americans considered occupying Ireland.

The Australia-First cause, quite ironically as NA more or less noted, was vindicated by the taking of Australian independence by John Curtin after ‘Pearl Harbour’ and the fall of Singapore to Japan. Australia illegally declared war on Japan (that was deliberate as our country had no right to declare any war and it was a seizure of independence from Britain), recalled our military from the Middle East, defied Churchill, mobilized the nation for Total War (the slogan was ours and not that of Dr Goebbels) and instituted its own foreign policy.

Indeed, we might say that Curtin and Stephensen were both generated in the same ideological bio-soup! When the chips were down, the policy for Curtin was ‘Australia First’. Those few months between December 1941 and March 1942 when Australia truly stood alone and defended itself by its own resources was a brief Australian moment at revolution.

Prime Minister John Curtin 1885-1945

In Curtin’s case, he took power amidst Britain’s failures in Asia, in pure crisis and the threat of invasion. It was in that scare of invasion and the fear of collaborators that the Australia-First Movement was suppressed in March 1942.

Perhaps the philosophizing of The Publicist had served to suggest the Australia-First people were unreliable and dangerous and possibly Axis sympathizers and traitors? I think that notion, fuelled by the Communist Party of course, still missed the entire point of Stephensen – his utter Australo-centric world-view.

The advent of war in September 1939 put the Publicist in a bit of a bind, but it did not stop its nationalist advocacy. Were there examples of policy to draw on?

In that sense, P.R.Stephensen had always taken stock of Australia’s place in the world and our national mission – Australia for the white race (see The Foundations).

We were not a great power and had to protect our own interests. The interests of Germany and Italy were not necessarily our interests at all, but they were far away and their impact was to draw British power away from its far-flung colonies, giving a priceless opportunity to build the nation the way we wanted and without the imperial overlay.

It was in his estimation hardly treason to put our own country first. Treason to whom, he once asked.

So why is Australia-First logic treason (as suggested in the arrests and internment) and was it lending succour to Japan or the fascists?

Let me use a dab of colour.

The notion that Inky in place of John Curtin wanted to stand on the steps of Sydney Town Hall, slouch hat on head, giving a Roman Salute to goosestepping blokes in khaki or jungle-greens heading somewhere to war – would be absurd. That theatre isn’t for Australians.

Indeed, if P.R.Stephensen was a fascist, he never saluted anyone and would have found that quite comical.

Saucy book-writer D.H. Lawrence was a good mate of Percy’s

Here I note some real irony. The NA writer did observe that P.R.Stephensen appeared to have castigated fascism early on, but what did he really mean? Stephensen wrote in 1935: “When the Hitler minded in Australia develop a little more self-confidence … to seize power, the press which now tacitly encourages them … will feel the weight of the rubber truncheon … for Fascism is a school-bully armed.

It has no intellectual pretensions, aims at discipline from above … The tradition of the AIF will … defend us … should the nasty little plotters ever screw up the courage to the point of putting matters to the test.

The ‘Heil Hitler’ buncombe which goes with Fascism will be treated with all the contempt such preposterous saluting and goosestepping deserves …”

Who were these “Hitler minded?”

A knowledge of Stephensen’s life and Australia’s Depression Era history, tells us that it was the group of Old Guard, New Guard, White Army and Emergency Committee, those armed and/or fighting organisations of Anglo-imperial conservatism.

If P.R.Stephensen labelled these people ‘’fascist’, he would be quite wrong by definition, but on the other hand, he was also differentiating his radical nationalism from forces who intended to impose anti-national government to preserve imperial capitalism, those better-people, or the “British Garrison” as he dubbed them, folk whose external behaviours might even look like fascism at a glance.

Confused?

Look at the New Guard. They adorned themselves in uniforms, saluted as fascists and praised fascism. But they were reactionary conservatives. Conclusion: what looks like fascism might not be fascism – oh, and possibly, vice versa.

So why is Australia-First logic treason (as suggested in the arrests and internment) and was it lending succour to Japan or the fascists?

Significantly, it was in the ranks of these imperial conservatives that the Brisbane Line conspiracy was hatched in early 1942, a plan to surrender part of Australia to the Japanese and ‘collaborate’ with them till war’s end.

And, it may well have been forces within that milieu which created a treason plot around Australia-First and interned them, thereby covering up their actual treason!

History is the constant reinterpretation of the past said political philosopher Francis Parker Yockey. Further, he opined correctly that ‘we’ (he wrote the words in 1948) know more of historical events than the people who participated in them.

What would Australia-First have thought of the official German and Italian attitudes towards Australia and Australians – had they actually known?

I had the displeasure of looking at two doctoral theses about the German case, one now books:

- Barbara Poniewierski, “The Impact Of National Socialism On German Nationals In Australia And New Guinea”, University of Queensland, 2006

- Emily Turner-Graham, “Never Forget That You Are German: Die Brucke, Deutschtum And National Socialism In Inter-War Australia”, University of Melbourne, 2008

Then I endured: “Gianfranco Cresciani, Fascism, anti-fascism and Italians in Australia, 1922-1945”.

Sadly, I found negative stuff. The view of German officials in Australia and their adjunct ‘Nazi’ organisations was that Germans should never assimilate into Australia and that Australians were not really a Nation at all.

Bad luck fellas. Many of us had some German blood and were quite happy about it. What would Australia-First have thought of the official German and Italian attitudes towards Australia and Australians – had they actually known?

The Italians too thought it “dishonourable” that Italian migrants mix in. Many did but many did not.

What was this? A fascist version of multiculturalism?

Then there were more sinister things. What about some German clowns who drafted memoranda that opined that Australia could be divided with Japan and Aussies of Germanic background shipped off to the “Russian Eastern territories” as settlers, I assume, to replace the inferior Slavs?

None of that would have accorded with what Miles and Stephensen had expected of fascism in their scheme to have it weaken the old Empire that a nationalist state could emerge.

Whatever the circumstances (to paraphrase the Irish saying) ‘Britain’s problem is Australia’s opportunity’, and Australia had an opportunity in the clash of ideologies and states to leave the European wars and strike out alone.

Let me be frank; the assimilation of Euro migrants, be they Germans or Italians, by an assertive nationalist government and its defence of the nation from partitioning, were possible things because the alternatives were really beyond the direct power of the fascist states to do otherwise.

They might tinker, but they lacked the power.

Whatever the circumstances (to paraphrase the Irish saying) ‘Britain’s problem is Australia’s opportunity’, and Australia had an opportunity in the clash of ideologies and states to leave the European wars and strike out alone.

But it was the alliance with Imperial Japan undertaken by Germany and Italy that was the decisive fact that threw the game into absolute chaos. Whether Miles and Stephensen and even Curtin too had thought of being at peace with Japan and also being more independent towards the Empire was obviated by that fact.

Japan was coming. Hitler, who the fetishists today would tell the new Aussie patriots and nationalists was some sort of ‘white nationalist’, had essentially abandoned the Western Pacific to an Asian power and endangered the white lands of the South Pacific for good measure. He may have ‘regretted’ the fall of Singapore (as he said), but he didn’t junk his alliance with Japan either.

Again: Australia-First nationalism was about Australia alone. Australia and its wealth and opportunities were ours. Australia-First nationalism was the ultimate rejection of the alien alliances, the fawning, the bowing and scraping to things foreign. It had the cultural element because the culture was politics Miles and Stephensen said, and an independent country must represent a new culture and a new culture demanded an independent country.

If Miles and Stephensen, The Publicist and Australia-First, were fascist, then it was in the context of an Australocentric nationalism that sought the rebirth of our country alone.

Had it come to power in whatever way imaginable (even as a guiding star for Curtin?), then it would have charted that new course for a new country.

That whole Australia-First experience is now essential myth for us to rescue a country under vastly different, but equally deadly – challenge. We have to dream the dream of Australia for the Australians, Australia alone.

Howsoever we get there, whomsoever we may bloc with, whatsoever we have to do to get there, means we become hard pragmatists, idealists but practical ones attuned always to facts and maybe even sharper than they.

And if someone said to me, that this Australia-First myth was ‘fascist’, I would just say: “Quite frankly, I don’t give a damn.”

In 2000, the author of this piece, Jim Saleam contacted Oxford university which was nice enough to issue Percy’s degree. At the time, Percy refused to cough up the pound it was worth to him. The university, understanding P. R.Stephensen’s historical importance, issued it for free.’

Further Reading:

Percy Reginald Stephensen (1901-1965), by Craig Munro, published in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 12, (MUP), 1990. http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/stephensen-percy-reginald-8645

Percy Reginald Stephensen (1901-1965), writer, editor and publisher, was born on 20 November 1901 at Maryborough, Queensland, eldest son of Christian Julius Stephensen, wheelwright, and his Russian-born Swiss wife Marie Louise Aimée, daughter of Henry Tardent. Percy attended Biggenden State School, then boarded at Maryborough Grammar.

At the University of Queensland (B.A., 1922) he acquired the lifelong nickname ‘Inky’ (from the popular wartime song, Mademoiselle from Armentières); he also made friends with two returned servicemen, Fred Paterson, the communist, and Eric Partridge, the lexicographer. Norman Lindsay’s son, Jack, introduced him to Brisbane radicals and intellectuals.

P.R. Stephensen edited the university magazine, Galmahra, in 1921 and caused controversy by including Jack’s erotic lyrics. That year Stephensen joined the Communist Party of Australia. After graduating, he taught at Ipswich Grammar School in 1922-23. To everyone’s surprise, including his own, he won the 1924 Queensland Rhodes scholarship and left for England in August.

Reading philosophy, politics and economics at The Queen’s College, Oxford, P.R. Stephensen joined the university branch of the Communist Party with A. J. P. Taylor, Graham Greene and Tom Driberg, an undercover agent for MI5. Threatened with expulsion by the university authorities for his communist agitation, P.R. Stephensen was involved in the 1926 general strike and, after it failed, helped to organize the Workers’ Theatre Movement in London.

Graduating with second-class honours in 1927, P.R. Stephensen joined Jack Lindsay and managed the Fanfrolico Press at Bloomsbury, London. He devoted his energies to literary and fine press publishing, issuing about twenty titles in 1927-29: all lavishly printed and illustrated limited editions, they included works by the Lindsays and Hugh McCrae, as well as his own translation, The Antichrist of Nietzsche. He also co-edited with Jack the literary magazine, London Aphrodite.

P.R. Stephensen began living with a former ballerina Winifred Sarah Venus, née Lockyer, with whom he shared the rest of his stormy life. They married, after her husband’s death, on 7 November 1947 in Melbourne; Winifred raised a son Jack from her first marriage.

After meeting D. H. Lawrence in December 1928, P.R. Stephensen established the Mandrake Press (1929-30) — with backing from a Bloomsbury book-dealer — to publish Lawrence’s controversial paintings.

As a champion of Lawrence, he took part in a spirited anti-censorship crusade, writing satirical pamphlets and arranging with Lawrence to produce a secret English edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. He also published his own collection of Australian stories, The Bushwhackers (1929), as well as work by Jack McLaren and others, among them the legendary Aleister Crowley.

Returning to Australia in 1932, P.R. Stephensen established the Endeavour Press in Sydney with Norman Lindsay, producing over a dozen titles by such writers as Banjo Paterson and Miles Franklin. Disagreements with the board led to Stephensen’s resignation in 1933. He set up his own under-capitalized firm, P. R. Stephensen & Co., which brought out another dozen Australian books by Franklin, Henry Handel Richardson, Eleanor Dark and others. The company’s inevitable demise in 1935 delayed publication of Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia until 1938.

With the failure of his publishing ventures, Stephensen became active as a polemicist and organizer. The attempted banning of the Czech writer Egon Kisch from Australia in 1934-35 prompted Stephensen to lead a rebellion against George Mackaness in the Fellowship of Australian Writers; ‘Inky’ was supported by Frank Clune, for whom he was to ghost-write almost seventy books over the next thirty years. Stephensen expanded a long essay for his short-lived ‘national literary magazine’, Australian Mercury, into The Foundations of Culture in Australia (1936) which was his most significant achievement and one of the most stimulating works of the 1930s. Its influence led to the formation of the Jindyworobak poetry movement.

Publication of the book was financed by a new patron William Miles who, with Stephensen’s assistance, in July 1936 launched the monthly Publicist; it had a strongly anti-British, anti-Semitic and anti-democratic flavour by 1938 and was criticized for its overt Fascism. An early champion of Aboriginal rights, Stephensen helped to organize the ‘Day of Mourning and Protest’ to mark the sesquicentenary on 26 January 1938.

The central puzzle of Stephensen’s life was his sudden shift of sympathy from the left to the far right. If his need to rely on the patronage of Miles was one reason, another was his frustration at his own business failures. The widely-publicized Moscow trials of 1936-38 convinced him that communism was no longer a solution. Disillusioned with democracy, he now looked to extreme nationalism, although he idolized Gandhi rather than Hitler. Like conservative Australian politicians, Stephensen showed admiration for Japan.

In October 1941 Stephensen formed the Australia-First Movement, a political pressure group based on the programme advocated by the Publicist. Military Intelligence, after failing to have the group banned, used a plot concocted by an agent provocateur in Western Australia to implicate Stephensen. He took over as editor of the Publicist in January 1942, but was arrested and interned without trial on 10 March, with fifteen other A.F.M. members, on suspicion of collaboration with the Japanese and of planning sabotage and assassination.

There was uproar in Federal parliament and criticism of the Labor government when it became clear that there was no genuine connexion between the Western Australian ‘plot’ and Stephensen. Yet he was held without trial in various internment camps for the rest of the war. A Commonwealth commission of inquiry found that there were ‘substantial reasons’ for Stephensen’s detention, but this opinion was mainly based on pre-war evidence of his disloyalty to Britain and admiration for Germany and Japan. An official war historian, (Sir) Paul Hasluck, wrote that the detentions were the ‘grossest infringement of individual liberty made during the war’.

For ten bitter years after World War II Stephensen lived with Winifred in various parts of Victoria, sustained only by his ghost-writing for Clune. In 1954 their major biography of Jorgen Jorgenson, The Viking of Van Diemen’s Land, was published by Angus and Robertson Ltd; Stephensen’s memoir of the Fanfrolico Press, Kookaburras and Satyrs, appeared that year.

Having returned to Sydney with Winifred in 1956, Stephensen lived at Cremorne within sight of the harbour. He ghosted books for retired sea captains and published under his own name the definitive History and Description of Sydney Harbour (Adelaide, 1966). He wrote or edited many entries in the 1958 Australian Encyclopaedia, edited four volumes of William Baylebridge’s poetry (1961-64), was a foundation member of the Australian Society of Authors (1963) and worked as a literary agent. On 28 May 1965, after giving an enthusiastic speech to the Sydney Savage Club, he collapsed and died in the State Ballroom. Walter Stone gave a panegyric at his cremation. Stephensen’s wife survived him; they had no issue.

An intellectual and literary adventurer, as well as a political rebel, Stephensen was a talented writer and a brilliant editor. As a publisher he influenced the careers of major writers. In the 1930s he helped to improve the standard of Australian book design and production, and to stimulate more vigorous cultural and intellectual debate. Almost 6 ft. (183 cm) tall, Stephensen was of athletic build, with fair to reddish hair and a toothbrush moustache. A portrait of him by Edward Quicke, a fellow-internee at Tatura camp, Victoria, is held by the National Library of Australia, Canberra.

Select Bibliography

• B. Muirden, The Puzzled Patriots (Melb, 1968)

• P. Hasluck, The Government and the People 1942-1945 (Canb, 1970)

• E. Stephensen, Brief Biographical Memorandum of Percy Reginald (‘Inky’) Stephensen

• E. Stephensen, Bibliography of Percy Reginald Stephensen (Melb, priv print, 1981)

• J. Lindsay, Life Rarely Tells (Melb, 1982)

• C. Munro, Wild Man of Letters (Melb, 1984)

• Parliamentary Papers (Commonwealth), 1945-46, 4, p 941

• R. Fotheringham, The Life of P. R. Stephensen, Australian Publisher (B.A. Hons thesis, University of Queensland, 1970)

• R. L. Hall, Notes about P. R. Stephensen 1918-1932 (Fotheringham papers, University of Queensland Library)

• Stephensen papers (State Library of New South Wales and University of Queensland Library).

Bibliography

Non-Fiction

- The Bushwackers: Sketches of Life in the Australian Outback

- The Foundations of Culture in Australia

- The Foundations of Culture in Australia: An Essay Towards National Self Respect (1936)

- The Legend of Aleister Crowley (1930)

- The History and Description of Sydney Harbour (1966)

Secondary Sources

- Inky Stephensen: Wild Man of Letters, by Craig Munro (UQP, 1992) ISBN 0-7022-2389-1.